232

IT MAY NOT BE A LIVING, BUT IT'S A BUSINESS!

It is usually better to charge a flat fee

for design, than to charge by the hour. I

always think of plumbers, when I think of

hourly rates, and—nothing against

plumbers—the practice of charging by

the hour really denigrates our work in the

eyes of clients. Most clients would not feel

right about paying us as much per hour

as they do their lawyers, and if our work

doesn't take us long to complete (the com¬

puter has cut my work time in half on an

average piece of lettering or illustration),

we won't make much money.

From the standpoint of the client's psy¬

chology, it's better for us to charge a flat

fee, but break it down, if they ask us to,

into bite-sized chunks such as Discovery

phase, Execution phase,

Deployment phase, and

silly labels like that.

You'll make more money

charging flat fees, but

explain up front that

client additions or alter¬

ations cost extra, and these can always be

charged at an hourly rate!

Advertising agencies and design firms

always make clients sign contracts, which

usually include something like one-third

payment up front before any work begins.

Although I have rarely used contracts, my

advice to you is to use them, in most

cases. When working for large corpora¬

tions, publishers and ad agencies, they

will usually hand you the contract.

Remember that in every contract, the

writer will try to covertly gain legal and

financial advantage over whomever is

expected to sign it. Not when we write the

contract, of course. I mean the ones they

want us to sign.

I don't use contracts when I'm working

with small clients whom I sense are trust¬

worthy and seem to understand concepts

like kill fees. I have occasionally judged

poorly, but still I've only been burned a

few times. If you present a client with a

contract and he won't sign it, even one he

gets to negotiate on a little bit, I wouldn't

deal with him at all. The biggest problem

you'll ever have is working with what I

call the "amateur client" who has no expe¬

rience working with artists.

"Work for Hire" (WFH) is a corporate

plague upon artists everywhere. Clients

get away with making us agree to it

because too many of us realize that a job,

even with a WFH attached, is better than

no job at all, which is a situation free¬

lancers often experience. WFH means

that we are signing away our work and

all rights to it, forever, to our client.

Should our work, say a cartoon character

we created, or a logo we designed, go on to

have a greater and more illustrious life

than we, or even the client, initially envi¬

sioned, we have no right to demand fur¬

ther compensation for the additional

usage. Many designers make substantial

money selling secondary rights to their

work. I've resold one image, originally

done for a magazine cover, three addition¬

al times to other clients. Had I signed a

WFH contract I would no longer have

owned the art to sell.

There are designers who will not do

WFH and insist on placing their © on

Aside from talent, an artist will benefit most from

being able to self criticize, to be honestly

introspective...and to accept sincere criticism

from others without knee-jerk defensiveness.

every piece they do. If they can afford it, I

salute them. If I were designing a logo or

doing an illustration for some product

where the nature of the work was so spe¬

cific to that company, leaving little possi¬

bility for resale, and if the initial compen¬

sation was acceptable, I'd have no prob¬

lem with WFH. Some designers, as an

alternative to WFH, will offer to sell the

copyright to their work (which normally

reverts back to the artist) outright to the

client for an additional fee.

When you work as a company employ¬

ee, all that you produce is generally

owned by the company. I know a guy who

conceived the idea for a product that went

on to become phenomenally successful,

netting millions for his employer. At least

they gave him a small raise, but he had to

go to them and ask for it! Another guy, the

creator of one of the most successful car¬

toon series on cable, that has reaped 100

million dollars in merchandising alone,

has to content himself with "doing what

he loves" (but not sharing in the full

rewards) because he created the product

under a WFH contract. Just imagine the

glee of the network execs as they consid¬

er their high profits and "low overhead."

In addition to wanting to keep all the

money, corporations increasingly are try¬

ing to keep all the credit, too. There's a

growing reluctance by corporations to

acknowledge creators (or they might have

to pay them). Film credits, except for the

biggest names, seem to be moving to the

ends of movies, authors' bylines are get¬

ting smaller and smaller on book covers

and clients are increasingly reluctant to

let illustrators and designers sign their

work. Corporations seem to feel that an

artist's signature competes with the com¬

pany's logo or the product itself. The cor¬

porate entity itself wants to be known as

the sole creator. In the current hostile cor¬

porate environment, we all may end up

like the graffiti artists, signing our names

on walls in 5184-point letters.

WORKING ON SPEC

"On spec" means working for free, or

speculatively, in the hopes that you will

please the client and land the account. On

spec is often cloaked

as a competition. It's

really a way for a

client to get many

designers to work for

free and be able to

choose from perhaps

dozens of submissions. I once received

¥ 1,000,000 from a Japanese firm by sub¬

mitting the winning design of a trade¬

mark character. I agreed to produce

rough sketches on spec because I felt the

job was so "me." My gambit paid off, the

client agreed.

You may wish to accept an on-spec

assignment if you are just starting out,

have no other work, or need to build up

your portfolio. We can always show other

clients this work, even if rejected, and

claim it was used.

THE AMATEUR CLIENT

He may know widgets in and out—

that's how he made his fortune—but God

help us when we work for this amateur

client who understands nothing about

what we designers do. With entrepre-

neurship on the rise and the explosion in

publishing, it has become increasingly

likely that you will find yourself working

with amateur clients. The first rule is to

get some money up front, before you

begin working. Tell him it's because, "I

haven't worked with you before." And

make sure that, in the negotiating stage,

he understands all about sketch fees,

change charges and kill fees. If he won't

sign a contract for your services, that's a

good sign that maybe you shouldn't work

for him.

Although all clients can be guilty of the

following gaucheries, you may be able to

spot an amateur client by these signs.

LOGO, FONT S LETTERING BIBLE

233

You know you're in trouble when a

client tells you...

1. "/ can only afford to pay you $150 bucks

for a logo because I still gotta pay the

printer, the billboard guy and the fabrica¬

tor who'll stamp your logo in gold on the

stainless steel case."

Obviously, the client values everybody's

work except yours and he's willing to

invest perhaps $50,000 in a product

based on a logo he claims is only worth

$150 to him. Not only is this insulting to

us, it marks the client as an idiot.

2. "I just need a simple logo. That should¬

n't take you too long, right?"

Sometimes the simplest logos take the

most time. The client is trying to say (a.)

he doesn't want to pay us, and (b.) he

doesn't value our time or our process.

3. "Look, if you'll do this job cheap for me,

next time, when I've got a better budget,

you're the one I'll call."

The client is trying to con us. Again. The

way this actually works is that by accept¬

ing a job for less money than the job is

worth, the client loses respect for us and

next time, when he has a better budget,

he calls another artist whom he respects;

who would never have taken a job that

paid as poorly as the one we accepted.

4. "But thisjob'll be a great portfolio piece

for you."

Translation: I don't want to pay you.

Sometimes, it may be worthwhile doing a

job that will have great exposure and

enhance your portfolio—even for free. But

again, this is just another client ploy to

pay us less than we deserve.

5. "/ can't afford to pay you anything up

front, but I'll pay you a percentage once

the product takes off."

Forget it. You'll never see a cent. If the

product does become successful, will you

ever be sure you're receiving a proper

accounting? Certainly, there are cases

where an honest client lived up to his

word in full, but such clients are rare.

This is another con.

6. "That printer was an !i!ssh'hle, he

screwed me and I won't pay him."

I worked for the owner of a small record

company who always found supposed

flaws in whatever typesetting or printing

services he contracted for and used these

as excuses not to pay anyone. Should I

have been surprised when later he

refused to pay me for some reason or

another? Some clients will agree to pay

the designer COD until we become com¬

fortable with him. Then when our useful¬

ness to him ends, he hesitates to pay a

few bills and finally skips out on us.

7. "One-thousand bucks for a logo?! Say,

I've got a guy who'll do it for $100."

"So let him do it," I told the client who

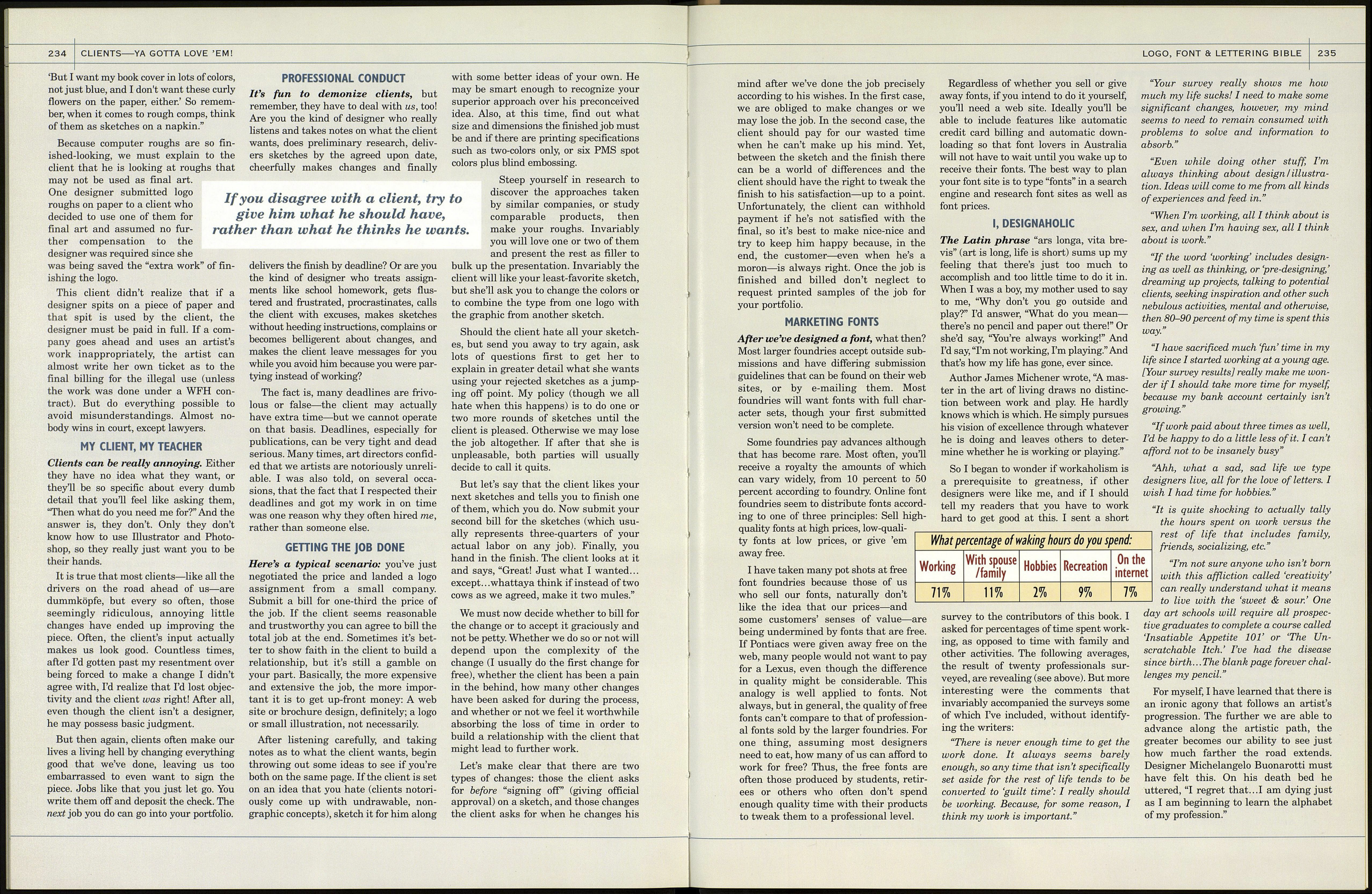

What a basic BILLFORM looks like:

Your Personal Logo or Name Here

Your address/phone/fax/email/web site underneath

Date:

Bill to: Client's name

and address here

P.O. #: Your Job number—just make something up.

Client's Job #: If they give you one

Job Description: Leave space here to fully describe the services

you will provide in return for...

Total: The amount you want to be paid

Your Signature,

an insipid one. Ideas, for books or prod¬

ucts, are usually not very stealable (al¬

though there have been notable excep¬

tions!) because an idea is nothing without

its creator's energy behind it. Conversely,

even a silly idea can become a mega-hit

when someone who believes in it strongly

enough puts all his energy behind it.

Publishers will generally not steal a book

idea because they'd have to hire

someone else to write and/or

design it, so why not just let you

do it in the first place?

10. "I don't want the logo to be

too slick or it'll scare away my

working class customers."

Every night in their living

rooms, the poorest and least

sophisticated among us (along

with the rest of us) watch the

most expensive and technologi¬

cally advanced, state-of-the-art

television shows and commer¬

cials created by the highest-

paid designers on earth. But

your client wants you to dumb

down his logo. Well, okay...if

he's paying!

Your S.S.# or tax ID#: Don't volunteer unless requested.

URLS BEFORE SWINE

Thank You! Please pay within JO days of receipt.

called me up a month later willing to pay

the thousand for the same logo. "What

happened to the $100 logo?" I asked. "It

wasn't good enough," he admitted. Well,

you get what you pay for!

8. "I'm not paying for this logo because I

can't use it."

This is a tough one. The guy's business

venture collapses, or he simply changes

his mind, after you've done the finished

logo according to all his idiotic demands.

Legally, he has to pay you, and his own

circumstances are irrelevant. If you'd

been paid one-third up front and one-

third upon approval of comps, you'd only

be out one-third of the dough. If you had

made him sign a contract, you could take

him to court.

9. "I've got this million-dollar idea, see,

but you'll have to sign an NDA before I

can show it you."

Every time some smart amateur client

has called me up needing a logo and

insisting I sign a non-disclosure-agree¬

ment (NDA) to legally prevent me from

revealing his brainstorm to anyone else,

the idea when finally unveiled, has been

Rough sketches can be so

tight and quick to produce

when drawn on computer, that we are

tempted to provide the client with dozens

of them in the hope that if fifteen sketch¬

es fail to please, the sixteenth might. But

unless the client has requested, and is

willing to pay for, dozens of rough con¬

cepts, it's best to limit him to four or six.

Otherwise, the client gets confused and

can't choose, or he thinks it must be so

easy for us to whip out sketches, he might

as well see a dozen more to be sure no

concept has been overlooked. This just

reinforces the idea in most clients' minds

that design is not as valuable as the "real

work" of a printer or a lawyer.

Clients can be agonizingly literal.

Writer and artist Mark Clarkson

explains, "I always want to start the dia¬

logue as soon as possible, lest I go a long

way [making sketches] in the wrong

direction. But then the...urn...client

always takes rough sketches at greater

than face value. It's like if you were dis¬

cussing a design at a restaurant and you

grabbed a napkin and did a sketch. But

the client kept fixating on the wrong

issues like the color of the ink in your

pen, say, or the texture of the napkin: