ULJtv-.

Paul Shaw and Garrett

Boge's font Ghiberti, right,

is "a contemporary inter¬

pretation of the bold

Florentine lettering style of

the fourteenth and fifteenth

centuries." Donatello, below

right, is "a classically pro¬

portioned design inspired

by the lettering on the fif¬

teenth century cantoria by

Luca Della Robbia." Shaw

and Böge don't sit around

browsing through old

Hational Geographies for

inspiration. No, the peri¬

patetic pair spends time in

museums and libraries and

makes photos and rubbings

of period inscriptions.

ARS LONGA VITA

BREVIS EST.COM

LATI NA EX

MANHATTAN EST

LOGO, FONT & LETTERING BIBLE

203

Л

<-

F

SPIRRTIOn

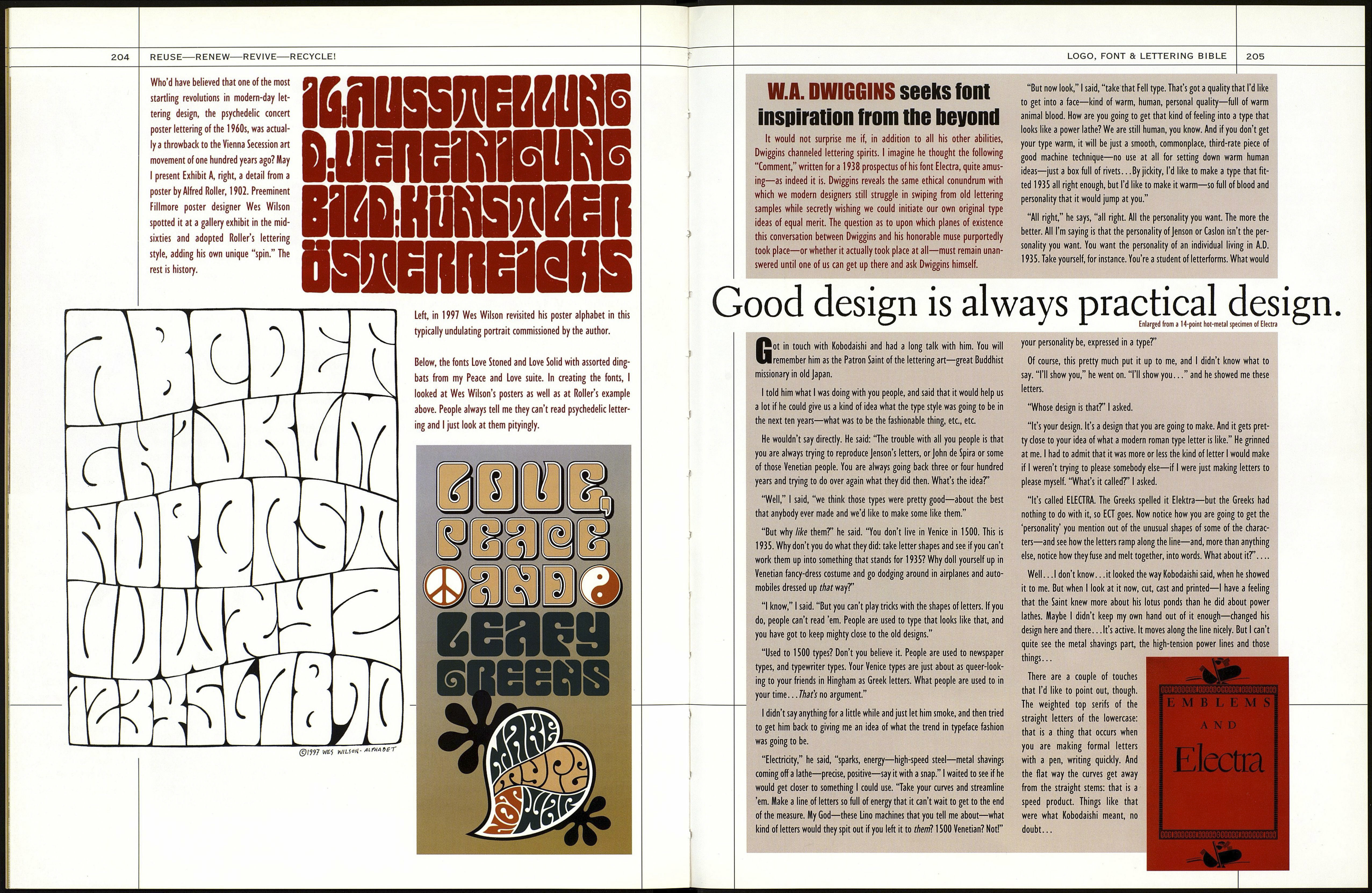

' ew ideas are entirely lacking in antecedents. Looking backwards, whether thousands

of years or to yesterday, becomes the vehicle through which seemingly new ideas spring into

being. Think of it as recycling. When it comes to type design, with its necessary adherence

to conventionalized letterforms and the need for some degree of legibility as its guiding con¬

straint, mining the past for viable models is often seen as a necessary, if not proud tradition.

That's not to say none of us ever come up with entirely original font concepts from out of our

own heads. Absolute originality in all our design work might be the highest goal, providing the

results are commercially viable. The designer's eternal dilemma—whether to adhere to accept¬

ed norms, or to create something so new and different that it might not be accepted—is explored

in the sidebar, next spread, reprinting Will Dwiggins's famous dialogue with his type muse.

Ideas for new fonts, as this section shows, can come from such obvious sources as vintage

signage, mosaic inscriptions, old print matter such as magazine ads and book covers, and even

from automobile and machinery nameplates. But type inspiration can also come from such

intangible sources as a dream, a comment or music.

Whenever we base a font that we intend to sell on someone else's design, we must ask our¬

selves: Is the designer dead and could his heirs sue? The very question reveals why so many

fonts are based on obscure sources in the public domain. Hopefully, we inject our own style and

personalities into every font we, uh, emulate, and this personal spin (which is usually just a fail¬

ure to emulate correctly ) helps us justify the theft: the highest compliment a designer can pay to

a dead one. Designers steal mainly for two reasons: We fear we cannot think up good enough font

ideas on our own, and we can't resist copying great old letterforms that inspire and excite us.

AMNPR

Every book on type must mention ancient Rome's famous inscription (c. A.D. 114) at the base of the Trajan

Column, and this one is no exception. The letters of the Trajan inscription, believed to have been painted

in brush before being incised, have been praised through the years as the finest example of classic Roman

lettering. And after that, the praisers try to fix it. Frederic Goudy fixed its flaws in his font Trajan, and so

did Carol Twombley—though not quite as much—in her digital version for Adobe. That's because the let¬

ters are very inconsistent, and they lean every which way. It's like the stonecutter had his eyes on the sun¬

dial, going chip, chip, "When's it gonna be five o'clock?" Look at the stem widths of H, above, compared

with R. The ? is different again. The late Father Edward M. Catich, noted Catholic typophile who made

extensive tracings of the inscription (from which come the five letters above), pointed out in his 1961

book, The Trajan Inscription in Rome, that few of the fonts based on the Trajan capitals—actually refer¬

enced from a spurious cast of the tablet in the British Museum—accurately reflected the original. But all

my nitpicking aside, the Trajan letterforms are piss-elegant and remain inspirational to this day.