200

TYPÉ: Beauty in Abstract Forms

"Good type design may be practiced only by an artist with

peculiar capabilities. The most essential of these is the ability

to discover beauty in abstract forms."—Frederic Goudy, 1938

"After four thousand years the alphabet has not reached

the end of its journey, and from all indications, it never will."

—George Salter, 1954

Do we really need another font? Some

designers, content with Times Roman,

Arial and Brush Script, would answer no. On

the other hand, many people—designers, as

well as normal people—"collect" fonts and can

never have too many. It may certainly be

argued that over the centuries almost every

conceivable variation on the alphabetic char¬

acters has already been thought up. However,

two forces conspire to ensure the continuation

of font designs for the future. The first is mar¬

ket forces and the need by foundries always to

refresh the stock on their shelves. The second

is the mania for adding one's own contribution

to the tradition of type design. There is some¬

thing unquestionably marvelous in seeing

An Exercise in Versatility

Matthew Carter on lettering and type

"There are significant differences between designing let¬

tering and designing type. With lettering—for a logo, an inscription in

stone, or a piece of calligraphy—you know ahead of time the letters and

their order. If a letter occurs more than once, you can vary its form accord¬

ing to how it combines with other letters.

"With type design, on the other hand, you don't have

the luxury of knowing the order. Typographic letters have a single form and

must be randomly combinable. And it's only in combination that letters

become type. Sometimes a student who is working on a typeface will show

me a single letter, a lowercase h for instance, and ask me if it's a good Л. I

say that I cannot judge it in isolation; it is only good or bad as it relates to

the other characters in the font. If the student sets the h next to o, p, v and

so on, then we can begin to see how it performs in context, and whether it

is good or bad, therefore.

"As the saying goes, type is a beautiful group of letters, not a

group of beautiful letters. Of course, many typefaces have had their origins

in lettering. A classic example is Herb Lubalin's Avant Garde Gothic, which

started life as a logo. The letters had to be adapted from the particular state

of a logo to the general state of a typeface, an exercise in versatility."

—Matthew Carter

words typed into a design program in a font of

one's own. I've said that it makes me feel,

somehow, like God.

If font we must, then what? Searching for

the unusual, the obscure, the rare overlooked

letter style is one approach. But the results

often are too weird for popular acceptance and

sustained usage. Most people won't buy prod¬

ucts that are too outlandish, which is why the

coolest automotive designs never make it past

the prototype stage.

Of course, there are many wacky display

fonts that have become wildly popular, but

one commercially viable option for font design¬

ers is to revive and/or tweak the classics—and

include free T-shirts and trance music CDs

with every font! It's astonishing to me, though,

how a basic-style font with a few subtle shape

variations can thrill us with its apparent

uniqueness. Christian Schwartz's Amplitude,

for example, seems at once familiar, yet brand-

new. The thirty-five-font family (two styles

BOLD FACE LYRE

Latest Quirky Sans

shown above) is suitable in all contexts and

brings both designer and foundry a nice price.

Question: When isn't Caslon Caslon?

Answer: When it was digitized sans sensitivity.

Today, virtually every historically popular

typeface is available as a computer font, but

LOGO, FONT S LETTERING BIBLE

201

buyer beware: There are vast differences in

quality! At the beginning of the Mac era, fonts

were desperately needed and many classics

were digitized hastily. Close inspection of such

fonts frequently reveals shocking flaws. If you

choose to revive a classic, try to copy it with¬

out ego, or make something different enough

that it becomes not a copy but your own.

The issue of legibility has been debated

since the beginning of type history. In Fred

Farrar's Type Book, 1927, the author writes,

"Since the origin of movable types, their prin¬

ciple function has been to express in simple,

readable type, the message of the writer,

whether it is a book or an advertisement."

Designer George Salter wrote, "In weighing

the merits of graphically inspired deviation

from assumed norms we must carefully avoid

arbitrary impairment of the act of reading for

the benefit of the joy of seeing. We must not let

the spice become the food, nor the accent

obscure the substance."

Fortunately, readers of today are said to have

become accustomed to a greater number of

fonts than in the past, and therefore a wider

variety of font styles is now legible to us.

Legibility is still important, since we designers

tend to emphasize form over function. The

designers of the 1960s psychedelic rock con¬

cert posters weren't especially concerned

about it, but the man who had something to

sell, promoter Bill Graham, was reportedly

always yelling at them about legibility.

Ken Barber, type director of House Indus¬

tries, beautifully expresses the current view.

He says, "Lettering can do much more than

simply communicate the message of an author

or a client who's trying to sell something. The

lettering itself can provide a kind of artistic or

aesthetic entry point for the viewer; it's capa¬

ble of eliciting an emotional response. I think

traditionally, the message is considered the

content and the lettering the vehicle to express

ABCDEF

aabcdegh

ABCDEF

abcdefgh

ABCDEF

abcdefgh

the content. However, lettering can be part of

the content and can also be the content—they

become one and the same thing."

The laws of typography were made to be

broken. But bear in mind that however dif¬

ferent and imaginative your fonts may be, the

underlying laws of balance, composition and

symmetry seem to be eternal. Look at Dada,

Deconstructivism, Bauhaus, Psychedelia,

Grunge, and Post Thisandthatism: The best

of the weirdest stuff still follows the basic

laws, just applying them in ways that become

harder to recognize. The only ones who think

these trends are new are either lacking in

historical perspective or are simply too young to

have experienced them the first time around.

Top left at a, enlarged from

the specimen sheet shown

in the background of page

199, are some of William

Caslon's early letters,

several printing generations

later. Their murkiness poses

a real challenge to a design¬

er seeking to reinterpret the

original style. At b, a mod¬

ern, perfunctory Caslon font,

awkward and graceless. In

contrast, at c, Matthew

Carter's Big Caslon (meant

to be set at larger point

sizes) is so scrumptious, I

want to lick it. Witness the

top of ^'s lower loop. One

can almost see traces of the

tool that engraved the orig¬

inal letterpunch. The alpha¬

bet's pen drawn origins are

also evident. This is no mere

revival of a Caslon font. To

me, this is Carter channel¬

ing the spirit of Caslon him¬

self.

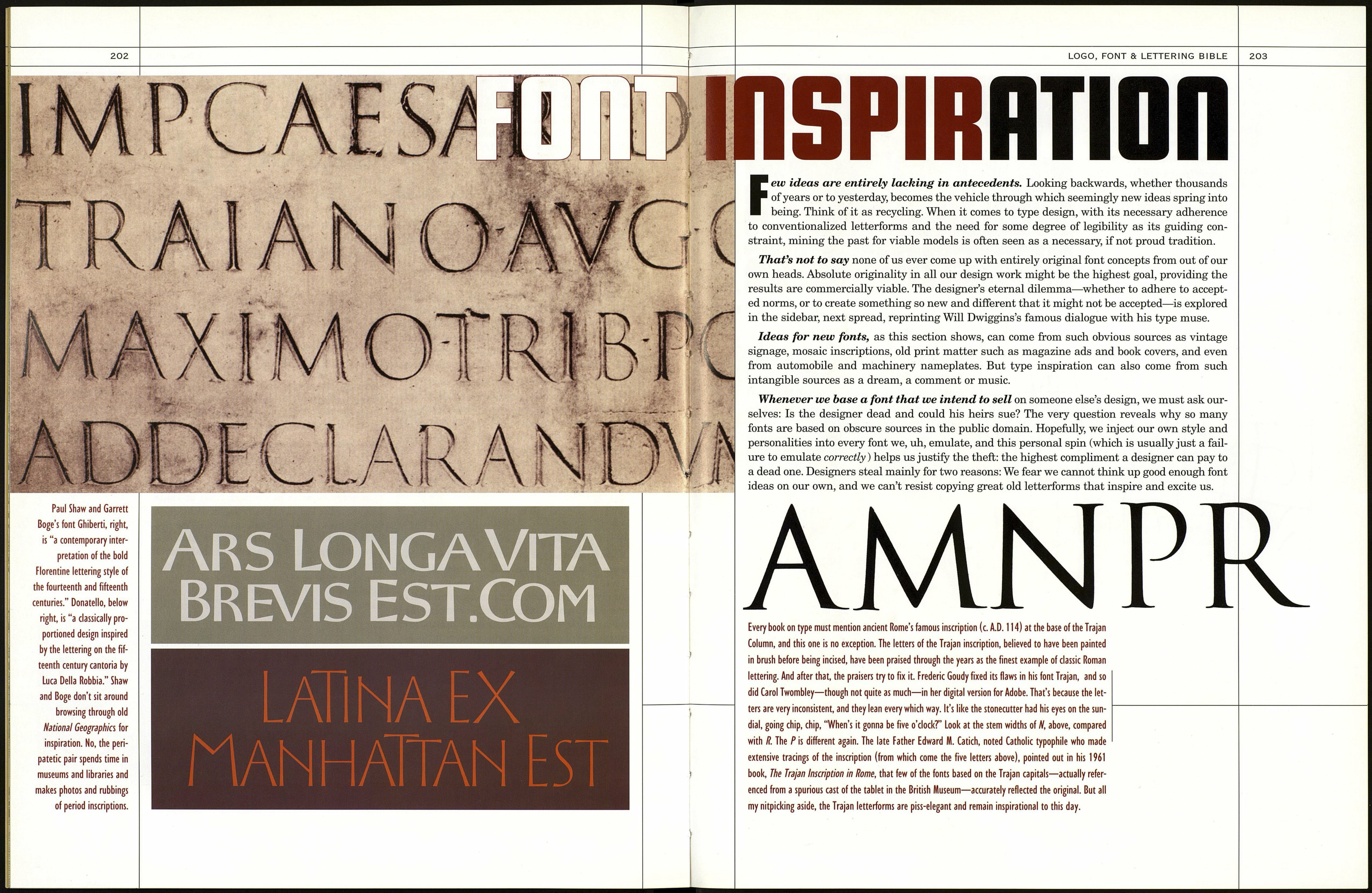

Right, Jonathan Hoefler's illustration of the difficulty in creating a revival from

poorly printed samples. At a, the 6-point S of Pierre Wafflard, from the 1819 Didot

specimen book. At c, a display-size I from the same specimen. "The challenge,"

Hoefler says, "is deciding which characteristics of these vastly different letters

should be preserved. In this case, I liked the thicks and thins of the larger size,

but I preferred the proportion and curvature of the smaller original—the ser¬

ifs starting further from the baseline and cap height, the lower bowl jutting out

further, and so on." Hoefler's hybrid 5, at b, is a paean to his perspicacity.