-176- range of decorative borders for Linotype. And he made use of

Some designers and stencils - or rather, templets - in his type designing, as we shall

their types see.

The wording on the title opening of The Time Machine was

not typeset but hand drawn; not really calligraphic, though part

of it is in a light script. The title and the name of the author,

designer and publisher are in a careful representation of typo¬

graphic letter forms. Beatrice Warde was perceptive when she

wrote, 'Mr W. A. Dwiggins has not yet published a type design;

yet his talent is above all typographic . . .' Although the quality

of his work as illustrator, book designer and decorator is a matter

for argument there need be no doubt about the standing of his

type designs.

Curiously, his first commission was not a book type, but some¬

thing quite different. In his Layout in Advertising, published in

1928, he had expressed a need for a better sans-serif type. 'Gothic

capitals are indispensible, but there are no good Gothic capitals.

The type founders will do a service to advertising if they will

provide a Gothic of good design.' A member of Linotype's staff in

New York read this and invited Dwiggins to design such a type.

(No doubt the Linotype people had already become aware of the

Erbar, Futura and Kabel types imported from Germany, had

recognised their own need for a modern sans-serif, and were

looking around for a designer.)

When Dwiggins's attention was drawn to some of the new

European sans-serif faces he conceded that the capitals were

good but thought the lowercase could be better. It was into the

lowercase of his own design that he put particular effort and

introduced some unusual features. It looks as though he and the

manufacturers were thinking of the new type as a display face, or

for use in short paragraphs of advertising copy, and not as a text

type for general use, because the face which Dwiggins actually

drew himself was the bold type, known as Metroblack. It was

issued to the public in 1929.

The capitals are a plain well-balanced set of letters, nearer

to the style of the Gill sans-serif than to the German faces. The

lowercase too, like Gill's design, is suggestive of traditional letter

forms rather than the 'new' geometric ones. The ascenders and

descenders, except y, are sheared at an angle - a good device, I

think, for 'humanising' the overall effect (see the chapter on

Rudolf Koch for his use of the same device.) The a, e and g have a

distinct variation in stroke thickness; it is more acceptable in the

a than in the other two letters, where the thin parts have an

unsettling effect on words. The most unnatural letters are f, t and

j, which are cropped at head or foot, so that they look as though

they have suffered damage in casting. Those defects in the bold

lowercase are not nearly so obvious in the light version, called

Metrolite, which was designed by Linotype but supervised by

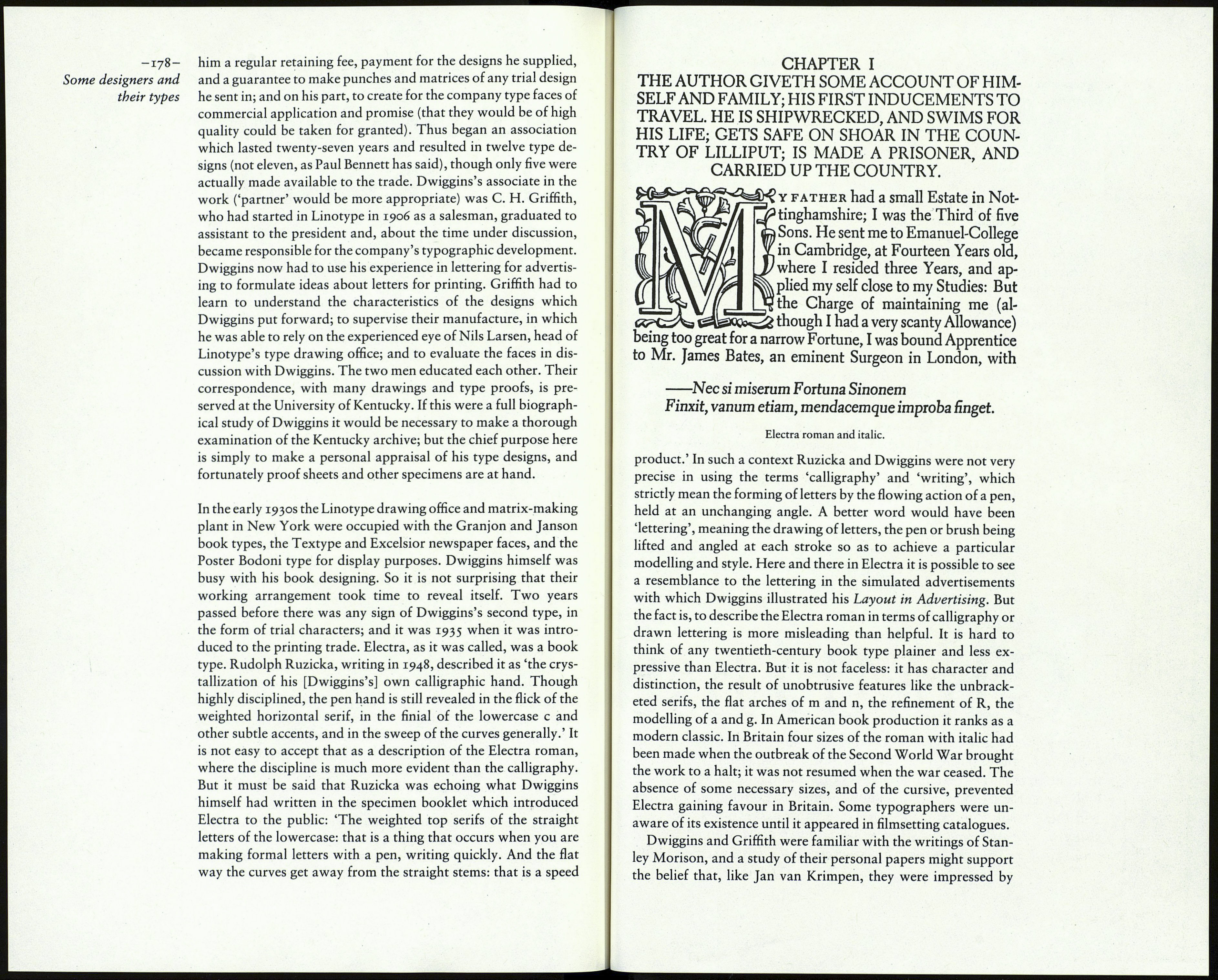

ABCDEFGabcdefghijk r.r,

ofW. A. Dwiggins

HIJKLM nopqrstuv

NOPQR wxyzab

AGJMNVWagvw,;"

ACIMNVWagvw,;"

Metroblack and its alternative characters.

Dwiggins. That applies to Metromedium, too. Taking the three

weights together, the widths of the characters are noticeably at

variance. In the bold, the foundation design, the width is normal.

The light face is wide, because its characters had to fit to the

widths of the bold characters with which they were duplexed.

The sprawling appearance of the light face probably troubled the

Linotype design people, because in the medium weight they

reduced the width — and rather over-did it. There was a fourth

version, Metrothin, available in the United States but not in

Britain.

Not long after the Metro faces were introduced it was evi¬

dently decided that they would gain extra favour if they could be

given some of the distinctive characteristics of the German sans-

serif types which were taking the eye of American printers and

their customers. Alternative versions of seven capitals were

designed (the W in two forms), five lowercase letters (the Jenson e

was later discarded), and three punctuations. These 'No. 2'

forms are the ones that are supplied in the photo-composition

fonts of the Metro faces.

In the United States Metro lost much of its popularity when

Futura became available for slug composition by Intertype and,

under the name Spartan, by Linotype. For over forty years

Metroblack and Metrolite have been used by British newspapers

for intros and crossheads, and have continued in use even though

other sans-serif types are available. There are certainly better

sans-serif types than Metroblack and its companions (and some

much worse); but though the design can hardly stand with other

types of its time - the work of Erbar, Renner and Koch in

Germany and Gill in England - it does have a degree of originality

which, from a first-time designer, deserves respect.

Linotype were sufficiently impressed with the type, and with

Dwiggins himself, to offer him a contract: on their side, to pay