, , -"*: ITU DIUM LITTER ARUM

Some designers and

their types

DER KUNSTKRITIKER

WISSENfúEBIETE

BUCHDRUCK

BREIS6AU

ARBEIT

RHEIN

Neuland: note the changes in letter shape from one size to another.

natural result when the letters were cut directly on the metal by

the designer. But was the design as artless and 'natural' as it

seemed?

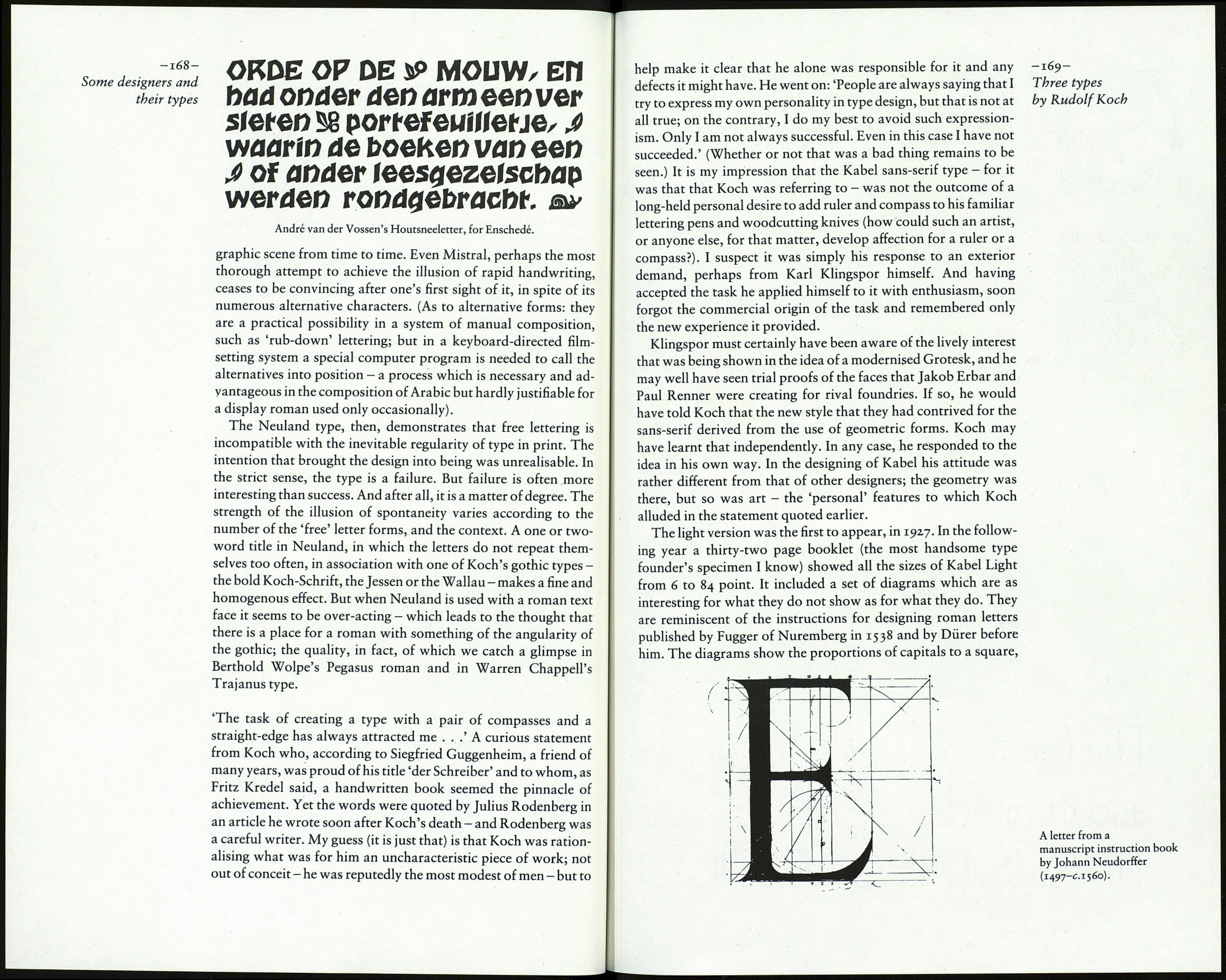

Some, but not all, of the letters vary in shape from one size to

another. Consider the E, for example: the treatment of the ends of

the horizontal strokes is so different from size to size as to make

one think the difference is contrived, not accidental. By contrast,

the shape of the S hardly changes; if it had done so, it could only

have become ugly or absurd. The thought occurs that some of the

variations are the result of intention, not chance; as if, having cut

the first size, Koch realised that an apparently random result in

the other sizes could only be achieved by deliberately shearing the -167-

strokes in another way, so that the E, for instance, would be Three types

noticeably different in one size from the next. A much greater by Rudolf Koch

illusion of spontaneity would have been gained if several vari¬

ations of each letter had been made in each size, to be used by the

printer at random, as was done much later in Freeman Craw's

Adlib type. That may indeed have been the intention, because

there are variant forms of C, R and U to be seen in the 28 point

(possibly the pilot size), but not in any other.

When in Dossier A-Z 73, Charles Peignot said, 'A clear dis¬

tinction must be made between lettering and type design. In

lettering, fantasy is of the essence; in type design, discipline is the

first requisite', he was stating a truth (though I would prefer

'freedom' to 'fantasy' and 'regularity' to 'discipline'). In the Neu¬

land type Koch seems to have been trying for the unattainable,

the perfect fusion of lettering and type; to put a free style of

lettering into a system - the ordered accumulation of letters in a

text for printing - in which the individual characters are essen¬

tially repetitive, the second and third A in a line being exactly the

same as the first. The more frequent the occurrence of a letter the

more it diminishes the illusion of spontaneity — at least for the

typographically trained eye. For the layman the casual effect may

seem quite convincing - until a line of Neuland is associated with

another type, when the contrast of the 'free' and the formal may

produce in the subconscious a vague sense that something is not

what it purports to be.

Erhebe die Напое,

Anpeikht,

urnamenloi

über mein H au pi,

dal feu Ich |i ürze in blitzende Siunden, rei»e mein Blut hoch in blühende Frauen, uno wiejie dahin in linkende Geigen *~ liehe ^ The Mendelssohn type. The point is made clear by the Mendelssohn type, which was

introduced by the Schriftguss foundry of Dresden in 1921 (two

years before Neuland) and used by the publisher Jakob Hegner

in books with woodcut illustrations. The 'unpremeditated'

appearance of the letters, particularly the e, is negated by the

frequency of their occurrence, especially when there are two of

them in a word. The same is true of the Houtsneeletter cut for the

Enschedé foundry in 1927, a similar exercise in the 'primitive'.

And the point applies equally to those informal script types,

simulating the effect of brush or pen, which appear on the typo-