-164- Sniffen to design a .close imitation of it, called Rivoli. Koch's

Some designers and design was perfectly suited to express in print the idea of

their types 'elegance' in social and business affairs. The type probably has no

place in the 1980s; the notion of elegance is under-valued now,

even when it is understood. But for the student of type design

Koch-Antiqua is interesting not only as an unusual type in itself

but for the contrast it makes with the next type to be considered -

a type from the same hand, and one of the most remarkable

designs of the twentieth century.

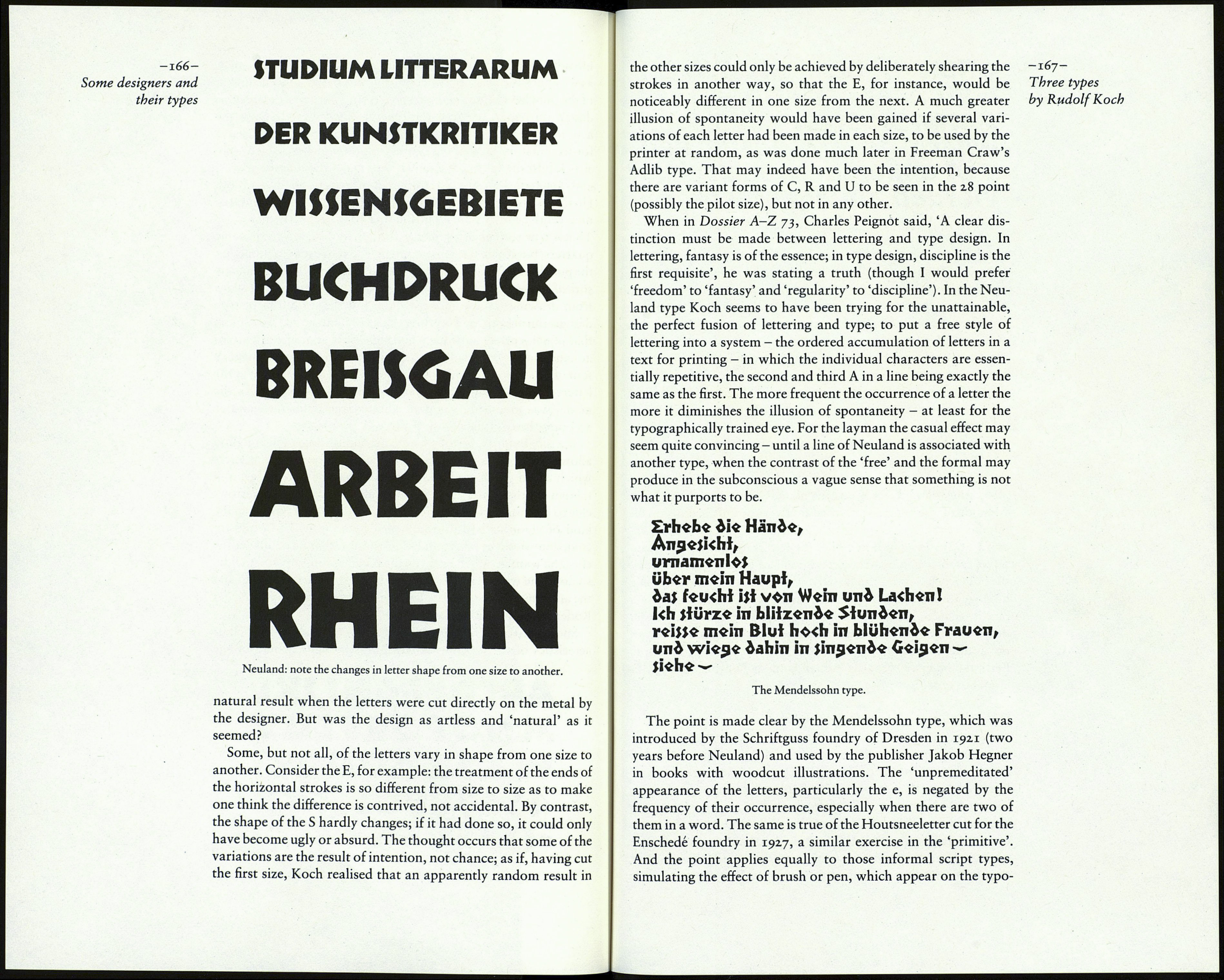

Koch's Neuland type appeared in 1923. It has two obvious char¬

acteristics: it is a sans-serif, and the letter forms seem to be unpre¬

meditated and 'accidental'. In both respects it is not the first of its

kind. Sans-serif lettering of the same blockish style had been used

to powerful effect on posters designed by Oskar Kokoschka in

Vienna before the First World War, the lettering looking as

though it had been rapidly cut from paper; and, as previously

EBS3

From a poster by Oskar Kokoschka, Vienna 1908.

noted, a primitive unregulated effect was the chief characteristic

of the titles in the woodcuts on the covers of Expressionist public¬

ations. The Neuland type is, though, entirely Koch's own in its

handling and realisation. And there is no doubt that it was his

own idea to create the type, not Karl Klingspor's. Klingspor dis¬

liked the face, but he respected Koch so much that he allowed it to

be produced (though he omitted it from his book on type design,

Über Schönheit von Schrift und Druck, published in 1949 shortly

before his death).

Neuland was much admired in its time. Francis Meynell used it

in 1924 for the Nonesuch Press edition of Genesis, where the type

accompanied a set of white-line woodcuts by Paul Nash. Stanley

Morison referred to the type as 'very fine'. The normal and the

inline version of the face were popular with advertisers in Britain.

And Monotype produced an imitation of it called Othello (its

name was the best thing about it). At the present time the face is

included in a catalogue issued by a manufacturer of filmsetting

equipment; but it seems unlikely that the type will regain much of

its former popularity, because of its distinctive and powerful

personality and the absence of a lowercase. Yet the design is well

worth examining, for reasons that will emerge.

In the first specimen of the type issued by Klingspor there is an

introduction signed by Koch himself. He begins by telling us that, -165 -

as was once the custom, the creator of this design and the maker Three types

of the punches is one and the same person. There was no previous by Rudolf Koch

design on paper, he says; the type emerged directly from the

action of the tool on the metal. The file alone produced the letter

forms - first in the shaping of the counter-punches, which were

struck into the face of the punches to make the interior spaces,

and then to fashion the outer edges of the letters. So far, so good.

He then says: 'Since the invention of printing until well into the

nineteenth century punch-cutting was done in exactly that way.'

That is true enough as to the physical operation, at least in some

quarters; but Koch's statement might lead the reader to think that

the punch-cutters of the past produced their punches without any

sort of reference in front of them. No doubt they did not work

from drawings of the modern kind; but the evolution of type

designs during the four centuries since Gutenberg makes it plain

that punch-cutters must have had some sort of model or pattern

at hand - a professionally written manuscript, a printed page, a

font of type, or a previous set of punches; and their shaping of the

letters on the metal, with whatever subtle divergence from the

model was intended, was premeditated and deliberate, and as

accomplished as time and skill allowed.

The final words in Koch's note are interesting. 'This method

allows a measure of freedom in the formation of characters

which could not have been achieved by any other means, and

therein lies the justification for the undertaking.' This is a strong

clue to his motive. I suspect that he wanted to see in type form the

kind of vigorous and untrammelled lettering he had often in¬

cluded in woodcut prints and block books; that he could get the

effect he wanted only by cutting the punches himself; and that by

so doing he was demonstrating his belief that the craftsman and

the artist should be one - a view he held strongly and sincerely, as

Rodenberg records.

Spontaneity and the fortuitous effect were to be the chief char¬

acteristics of the type; and that, it was thought, would be the

ABCDEF6HIJKL

MNOPQRÍTUV

WXyZAOU 121

4567890*,:*'!!

Neuland.