— ібо—

Some designers and

their types

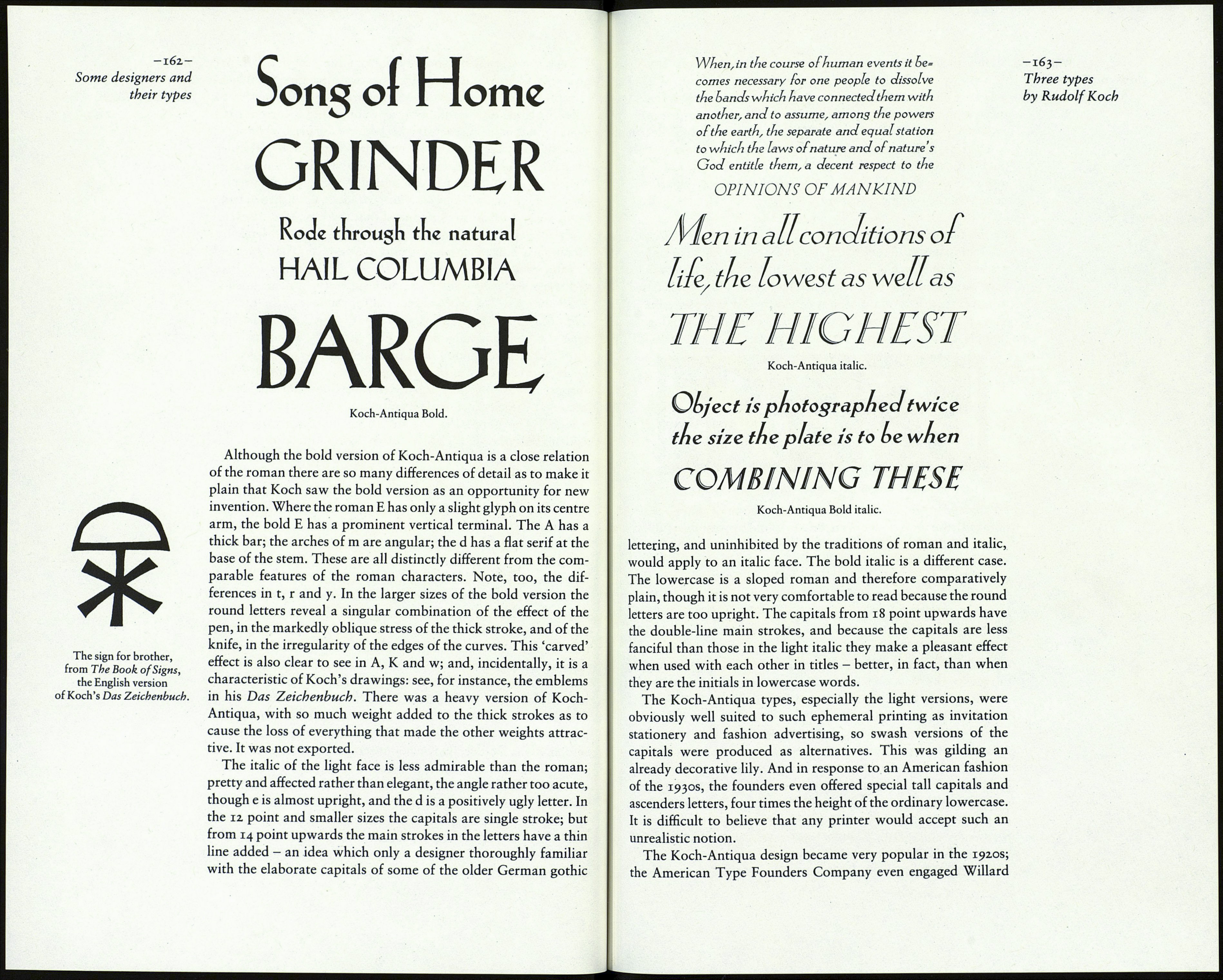

abcderghijklrnnop

qrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHU

KLMN

OPQ

RSTUVWXyZ

12345Ó7890

1 he annual picnic this year will

be bela at the new reservation at

NANTASKET BEACH

Koch-Antiqua roman.

Koch's first roman type, apart from the set of decorative -161-

capitals called Maximilian Antiqua, was the type known as Three types

Locarno in Europe and as Eve in America. In Germany it was by Rudolf Koch

called Koch-Antiqua; and because it appears in a current cata¬

logue in that name it seems the best one to use here. The roman

was issued in 1922, the italic in the following year and the bold in

1924. The origin of the design can be seen in a lettering exercise

done by Koch at the Offenbach school in 1921, and then repro¬

duced in his Das Schreiben als Kunstfertigkeit, published in Leip¬

zig in 1924. As Rodenberg pointed out, this was one of several

cases where Karl Klingspor, on seeing a piece of Koch's lettering,

encouraged him to develop it into a type face. The Klingspor

private press introduced the type in a special printing of Alfred

Lichtwark's Der Sammler; a sample page of it was included in

The Fleuron v. The type was chosen for the text of the Limited

Editions Club's Grimm's Fairy Tales (1931), where it must have

been the perfect companion to Fritz Kredel's woodcuts. The

Curwen Press in London used the italic for several books. But

Koch-Antiqua is not a book type; it is too mannered for that

purpose. I know of no type more elegant; but it must be said at

once that the elegance is deliberate, not artless; lively, not re¬

strained. The impress of the designer's personality, to recall

Rodenberg's phrase, is clearly visible. Koch-Antiqua is a highly

individual design. It reveals the working of a fastidious mind and

a skilful hand.

Anyone fortunate enough to have access to the type specimens

issued by the Klingspor foundry (the quality of their typography

and printing has never been equalled) should take time to study

this fascinating type letter by letter. The unusual characteristics

of the face are numerous. There is its weight, which is notably

light; the considerable height of the capitals and ascenders com¬

pared with the lowercase; the great difference in width between

B, P, R, S, T and A, C, N, O. There is the tapering of the vertical

strokes in the tall letters, a feature derived from the use of a

flexible pen. And there is Koch's distinctive lowercase g, making

its first appearance. Every letter shows something of interest,

often of an unorthodox kind. Note, for example, that h has two-

way serifs at the top of the stem but a single serif on its right leg;

that i has one serif at its foot but r has two; that the top half of s is

larger than the lower half; that the y is oddly out of character. (A

similar y was included in Koch's Jessen gothic type when it was

supplied to printers outside Germany. With its two oblique

strokes it was out of harmony with the strong verticals of the rest

of the alphabet. The letter y occurs rarely in the German langu¬

age. Perhaps German designers of the time had the same sort of

uncertainty about the correct form of the letter as there some¬

times is when a non-German designer has to draw the German

double-s character.)