-158 - unfettered attitude of mind. In regard to that it may be said that in

Some designers and Koch's time the designers of lettering and type faces in Germany

their types had a potential advantage over designers in other parts of the

world. They had two species of alphabet to explore and cultivate,

the gothic as well as the roman. Their creative powers must have

been vitalised by the richness of the one and the comparative

simplicity of the other. And because the roman was a fairly new

field of interest for them, designers were not constrained by a

sense of tradition, and one might expect that they would have

produced some fresh and attractive designs in the genre. It must

be said, though, that the roman types designed in Germany up to

1940 were respectable rather than notable, and the italics were

hardly more than serviceable - Wolpe's Hyperion being a distin¬

guished exception. Koch's only 'normal' roman design, the

Marathon, had so many inconsistent features as to make one

think he was not really interested in it.

The remarkable activity in the visual arts in Germany during

the first two decades of this century must have had a stimulating

effect on Koch. No doubt he was aware in 1905 that the desire

of young painters to free themselves from academic realism,

Impressionism and Jugendstil had resulted in the formation in

Dresden of 'Die Brücke', one of the most active groups in the

movement that came to be called Expressionism, whose purpose

was to externalise the inner world of the spirit, and whose means

were the exploitation of a 'primitive' style, unbroken colour and

the dissolution of perspective. Koch must have been particularly

interested in the work of those artists who used the woodcut as a

medium for highly charged effects on the covers of Expressionist

writings. When Koch began to produce illustrative woodcuts in

1919 he employed the same vivid manner of expression - the

violent-seeming tool cuts, the powerful contrast of white and

solid black - as had Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluf and others, though

in the examples I have seen his subjects are the simplicities of his

religious faith and his love of nature, not the manifestations of

emotional intensity so often characteristic of the Expressionists.

As to the harshly vibrant lettering that was sometimes to be seen

in Expressionist woodcuts, I think Koch's Neuland type is

evidence of his awareness of it and also of the value of working

directly into the material, though the type is much more disci¬

plined than was, say, the Mendelssohn type, of which more later.

It is in Koch's calligraphic work rather than his drawn lettering

or his type designs that the full effect of his own kind of ex¬

pressiveness is to be seen.

Another source of creative activity in Germany which must

have interested Koch, though it does not seem to have influenced

him much, was the Bauhaus. It was directed by Walter Gropius,

who had worked in Peter Behrens's architectural office, and

included Kandinsky, Klee and Moholy-Nagy on its staff. Its

troubled progress was brought to an abrupt end in 1933 by polit- -159-

ical power, just as its activities and ideals were beginning to make Three types

an effect. Koch may have had more sympathy for Gropius's state- by Rudolf Koch

ment that 'the sensibility of the artist must be combined with the

knowledge of the technician to create new forms in architecture

and design' than for Moholy-Nagy's belief that 'mathematically

harmonious shapes . . . represent the perfect balance between

feeling and intellect'; but in Koch's workshop in Offenbach he

and his friends took a simpler view: that the craftsman, with the

sensibility of an artist, should create forms which, whether new

or old, expressed the heart and mind of the individual.

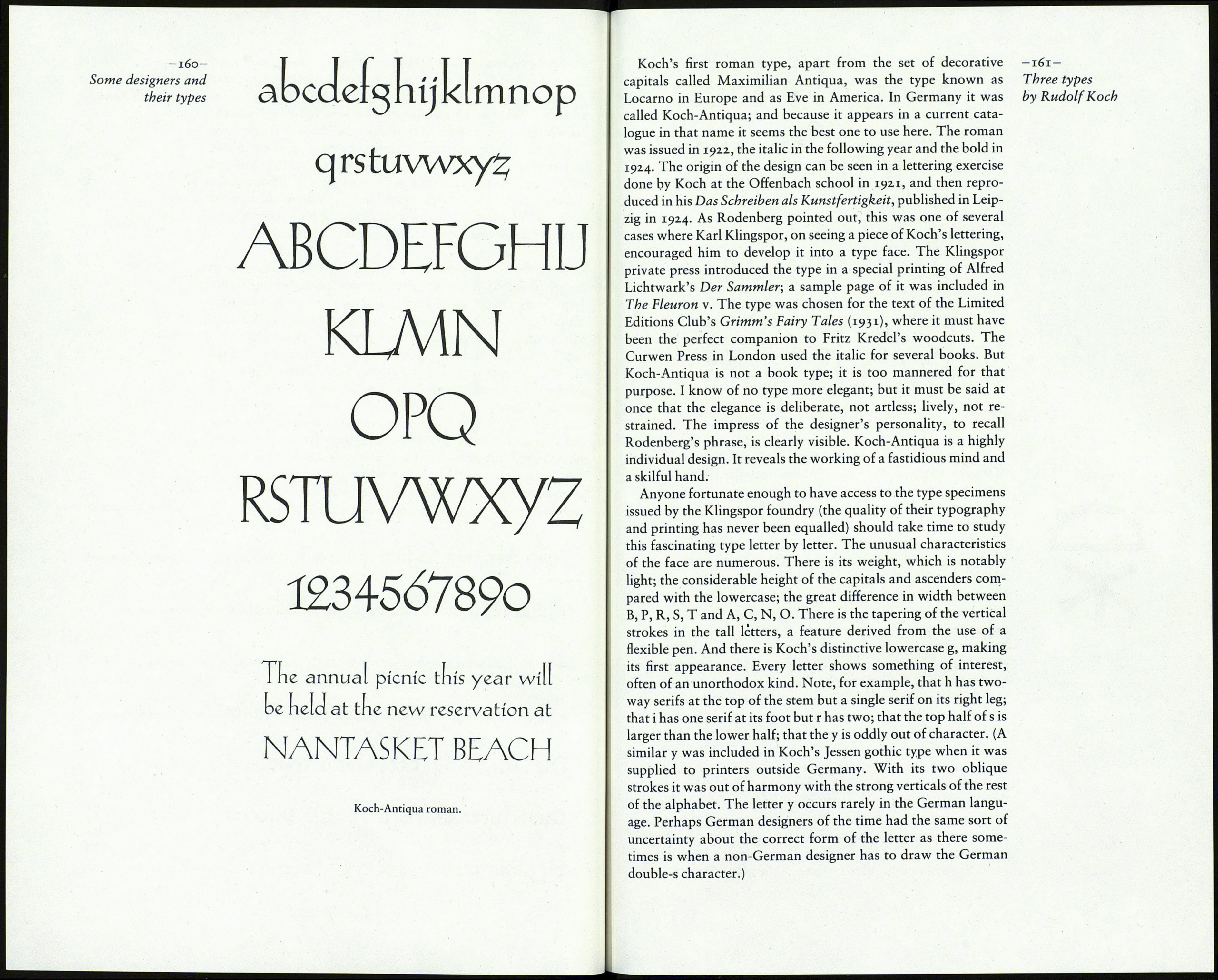

Koch's first type was the heavy weight of the Deutsche-Schrift.

It was issued by Klingspor in 1910, and light, bold and con¬

densed versions followed during the next three years. His other

gothic types include the Maximilian, the Frühling, the Wilhelm-

Klingspor, the Jessen and the round gothic Wallau, which Roden-

berg called Koch's most beautiful type face. And there was the

Claudius face, issued after his death. The variety, vigour and

richness of the letter forms in those types are easy to appreciate,

and the texture they present is a visual pleasure of a special kind,

making a page of roman seem, in comparison, noticeably pallid

and formal. A thorough study of the gothics, though, is a task for

more competent hands than mine. In any case, it is better here to

concentrate on three of Koch's roman types which not only

gained international favour when they were introduced but are

available now in at least one electronic typesetting system. Rudolf Koch's gothic types.

Jimtlíájtt Jcemoenfufycec оисф JHlen/hín Deutsche Schrift ыа.

Шс^осй íftagnec: Фес fliegende fjoUcmóec махшшнш.

£)íe jcfyônften 8шіД imbacci) en fur unfetß-^inbßß Frühling.

Síe^ulíutgcfd)ící)fe kl еигорШГфспЗШес

Die Grunòzuge bec gotífdien Maleceí Jessen

Ouvertüren unö Ягіеп сюп б» Puccini waiuu

Öt^äblungen аіш htm ©adjfentualb

Wilhelm-Klingspor.

Claudius.