-I56-

Some designers and

their types

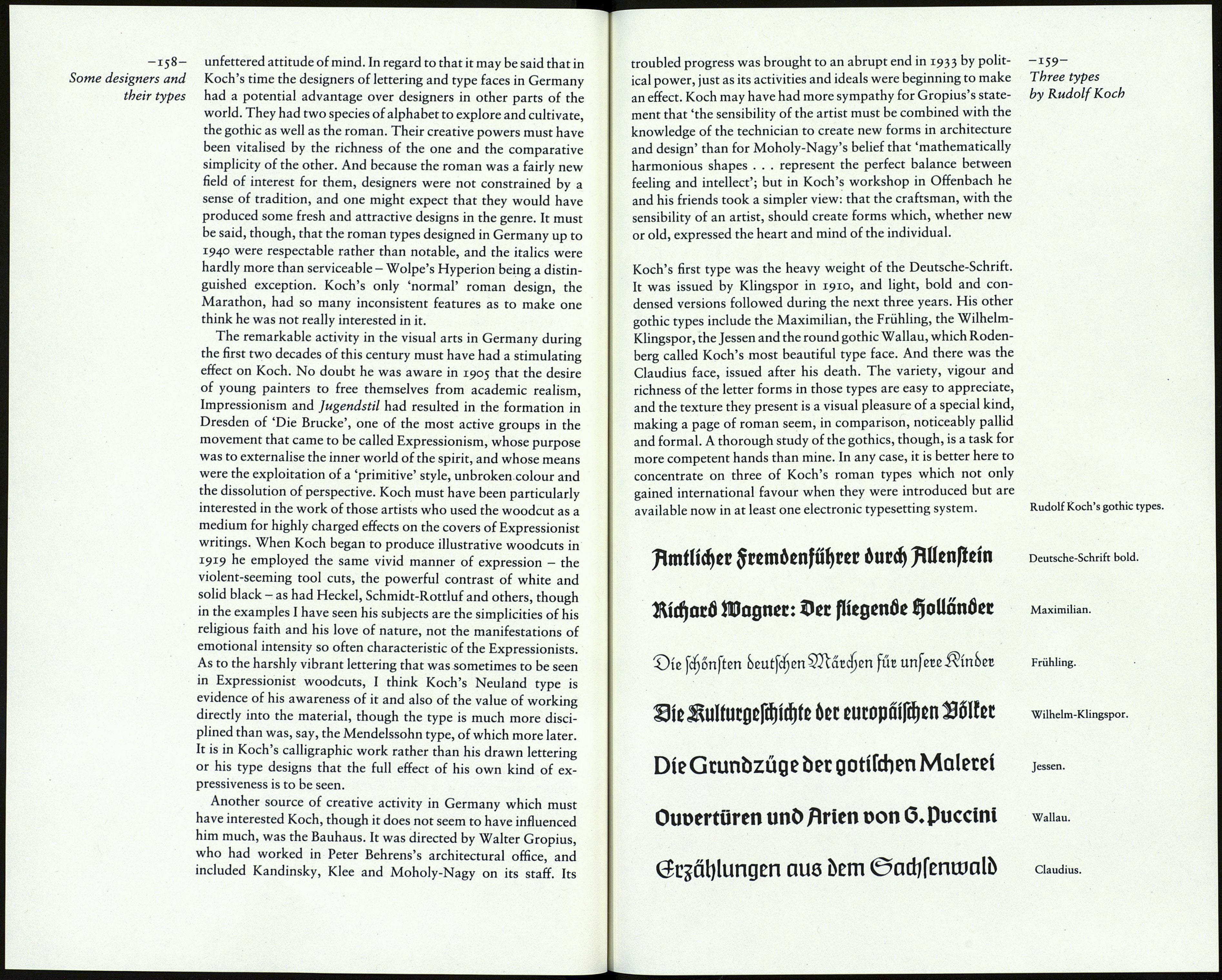

The g in the Satanick type and the bold version of Koch-Antiqua.

under names of their own choosing: Morris-Gotisch, Archiv, and

Uncial. They even made light, heavy and open versions of it -

clear evidence of its popularity. (Incidentally, it may have been

the lowercase g in that type that took Koch's fancy so much that

he adopted its form for his Antiqua, Wallau and Kabel faces.)

German designers pursued the idea of a type combining the char¬

acteristics of the gothic and the roman. The government printing

office in Berlin produced an unusual calligraphic roman by Georg

Schiller, and Otto Hupp designed an interesting simplified gothic

for the Genzsch & Heyse foundry. In 1900 the Rudhard foundry

nature Poems

of ftenrp Scott

Illustrated bp Jobn Кіфагй Brounb

The Neudeutsch type by Otto Hupp.

WGRV few months, during recenf years, some

'literary or Typographical Knight Adventurous

I has started on the quest of the [lew Cype, - the

. type which is to be perfectly original, or, at the

least, altogether unhackneyed, and yet which is

to be so normal that no one will be able to object

to the form of any of the letters as fantastic or

I unfamiliar. Che quest is no new one, though an

unusual number of people are interested in it lust now. 3t has

The Eckmann face.

Catalogue exhibition

of tbe German empire

The Behrens type.

issued Otto Eckmann's type, an extraordinary design owing -157-

more to art nouveau than to gothic or roman. Rodenberg said it Three types

was a great success. About the same time the foundry issued a by Rudolf Koch

design by the architect Peter Behrens, similar to but rather more

gothic than Schiller's type.

These innovations caused considerable interest and discussion

amongst German printers, and a certain amount of punditry. In

1905 Klingspor published an essay by Gustav Kühl (now more

interesting to look at than to read) called, in the English-language

edition, On the Psychology of Writing. It put the argument for

the gothic as being the proper letter form in which to express

German culture, and for the roman as being easier to read, and

settled for an amalgam of the two,.such as the Behrens design. But

though the Eckmann and Behrens types made the Klingspor

foundry's reputation, they did not last long in favour. A conser¬

vative element continued to regard roman as appropriate only for

'foreign' work; but the majority of publishers and printers came

to see the advantage of allowing gothic and roman equal status

for the expression of the German language and, as time went on,

to recognise that only in the roman was it going to be possible to

create the variety of type faces needed to satisfy the demands of

publicity printing.

The gothic, then, continued in favour; but there was a general

desire to see it revitalised, a. task in which Koch took a dominant

role. He became the foremost designer of gothic faces. His first,

the Deutsche-Schrift (often called Koch-Schrift) became im¬

mensely popular. Of the forty-five types, including variations,

credited to Koch in the Handbuch der Schriftarten - many of

them, no doubt, drawn by others under his direction - twenty-

four are gothics, and it is on them that Koch's high reputation in

Germany is based.

'Lettering gives me the purest and greatest pleasure,' Koch

wrote. He owned a copy of Edward Johnston's Writing and

Illuminating and Lettering, and, as previously noted, he con¬

tributed to the Beispiele Künstlerischer Schrift, the books of

examples of lettering that Rudolf von Larisch began to edit in

1902 (C. R. Mackintosh, Georges Auriol, Alphons Mucha and

Emil Weiss were amongst those whose work was shown). Koch

probably found Von Larisch far more stimulating than Johnston.

As Alexander Nesbitt has pointed out, Johnston's efforts in re¬

viving historic writing styles and his teaching of the use of the

broad pen were, and are, valuable in the early training of the

student of lettering, but they were limited in their scope and

purpose and had little relevance to practical applications. By

contrast, Von Larisch encouraged inventiveness. His chief inter¬

est was in developing the creative abilities of students by the use

of all sorts of writing tools - brushes, ball-pointed pens and blunt

sticks as well as the traditional broad pen - and by a flexible and