-152- designed at the request of Lanston Monotype, to compete with

Some designers and the new sans-serif types then appearing from Germany. 'I attem-

their types pted to give my type a definite expression of freedom and a per¬

sonal quality not always found in this kind of letter.' He seems

not to have realised that, on the contrary, it was the strict geom¬

etry and the impersonal quality of Futura and Erbar which were

gaining the favour of the typographer and printer of the time.

Goudy never attempted a slab-serif type. Nor did he look with

interest at the modern face, with its severely vertical stress, strong

contrast in stroke thickness and unbracketed serifs. The Goethe

design was the one approach he made to that style, and that face

was only as 'modern' as is Bulmer or Bell.

Goudy's types, except for those he designed directly for

Monotype, were cast from his own engraved matrices, in which

the action of the rotary cutting tool makes it impossible to obtain

the precise angles and corners needed in hard-edge faces. It is

therefore tempting to think that he turned a practical limitation

into a prejudice of taste. There may be something in that; but it

seems more likely that he simply was not interested in those

classes of type design where plainness and impassivity are of the

essence. He wanted each new design to be clear evidence of his

individuality, so he preferred the old style model because it gave

him the latitude to express himself as often as he wished. But the

fact is that although in the old style form the subtle variations of

letter shape, stroke thickness, serif form and x-height are appar¬

ently inexhaustible, the designer himself has natural limits to his

versatility; he can create only so many designs in a particular style

which possess both individuality and consistently high quality.

To force himself to produce several dozen variations on the

theme, as Goudy did, was to over-stretch his talent. I think many

would agree with that comment, though not everyone will agree

with the criticisms of particular types that have been made in this

essay.

If I do not think that all the thirty or so designs selected here

from Goudy's considerable tally of types would stand every test

of critical judgement, I do believe that Goudy Old Style, Goudy

Text and the Heavy Face are very fine designs of permanent

value; and that if Goethe, Marlborough and Goudy Lanston

were to be reworked by a sensitive hand and eye they would be

gratefully received by discriminating book designers. Even if

those few types had been the sum total of his work in the field he

would have earned his high place in the ranks of twentieth-

century type designers.

15 : Three types by Rudolf Koch

In his description of the typographic creations of the Klingspor

type foundry Julius Rodenberg remarked: '. . . among the many

examples of modern types there are some . . . which may be

regarded as truly artistic because in them the personality of the

artist is paramount. Whenever the creative power of the artist is

so strong that the impress of his personality is still clearly dis¬

cernible in the finished type, even after it has passed through the

long and complicated manufacturing process ... we may speak

of a truly artistic type.' If Rodenberg was including in that ob¬

servation the kind of type intended for continuous text, as in a

book, many of us would want to modify, even reject, his state¬

ment. Long familiarity with the classic book types - the well-tried

Baskerville, Janson, Garamond, Bembo and the few other staples

of American and British book printing - has imbued us with such

a deep-seated preference for plain and unobtrusive faces that

some of us find it difficult to accept even such an excellent artistic

type as Palatino in that role, however willing we are to use it in

other sorts of printing. But Rodenberg's dictum is entirely ac¬

ceptable when the subject is a type meant for persuasion, as in

printed advertising, or for pleasure, as on an invitation card. I

find convincing evidence for that view in the type designs of

Rudolf Koch, the most important of the distinguished designers

who worked for Klingspor.

Rudolf Koch was born in Nuremberg in 1876, the son of a sculp¬

tor of very modest means who died when Koch was ten years old.

At sixteen a family friend in Hanau took him in as an appren¬

tice metal worker. Koch later wrote: 'With eleven hours work

every day and evening classes of two hours several times a week

[he studied drawing] the apprentice lived a strictly ruled life.'

After nearly four years he grew dissatisfied with metal-chasing

and was allowed to return to Nuremberg, where he enrolled in

the school of arts and crafts. He thought he should try to make a

career as a drawing master; was thwarted in that, and found

himself a job in a lithographic firm in Leipzig as a draughtsman

and painter, but soon gave it up because he thought he was in¬

competent. For a time he tried to sell his drawings privately, but

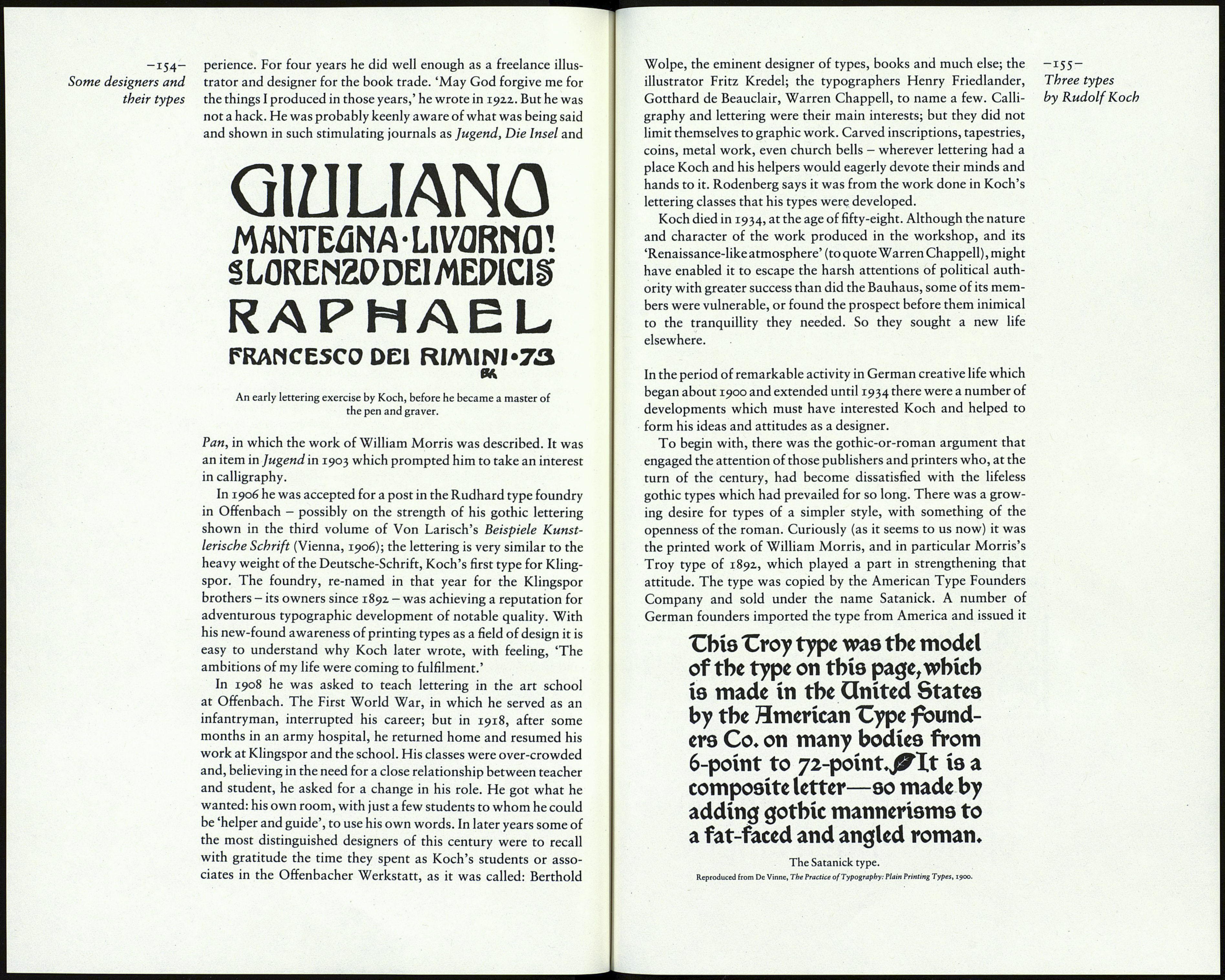

without success. Someone suggested he try his hand at designing

book covers. He did so ('water-lilies in the Jugend manner'), and

after what had been a long period of hardship he gained a post in

a bookbinding firm. The salary was modest but the job gave him

security, congenial work and the means of becoming a good

draughtsman. In 1902, after three years in the firm, he left it to

work on his own, this time with the advantage of practical ex-