-I20- unusually limited: his four roman text types, Lutetia, Romanee,

Some designers and Romulus and Spectrum, are remarkably similar in style. It is

their types as though he carried in his mind an image of a single perfect

alphabet, the quintessence of letters, and could do no other than

produce a representation of it on each occasion - even when, as in

Romanee, a particular model was in view and the task was speci¬

fied. Only in the Spectrum roman, a late work, is there any sign

that Van Krimpen had added to his vision an awareness of typo¬

graphic characteristics; but the awareness is not very obvious.

The hypothesis holds good for his italic types, too. His ideal

was evidently the written chancery hand of Arrighi and other

masters of calligraphy of the early sixteenth century, to the exclu¬

sion of later typographic models. If this were not so, if he had

shown equal willingness to take the italic types of, say, Granjon

or Fournier as exemplars, he would have worked as they did,

from a practical standpoint, fully aware of the need to make his

italics true secondary faces, subservient to and thoroughly har¬

monious with his romans. But the italics for Lutetia, Romanee

and Spectrum, and the Cancelleresca Bastarda that was intended

to work with Romulus, show that, whatever he thought he was

doing, he was actually concentrating single-mindedly on the

design of a perfect alphabet in the chancery mode, and was

probably oblivious to external considerations.

In short, Van Krimpen thought like an artist, not like a de¬

signer. He worked from an inner vision, not from a broad view of

practical realities and requirements. That is not the best frame of

mind (indeed, it is not the right one) in which to create something

which is to function in a variety of texts to the full satisfaction

of publisher and reader. In Van Krimpen's case the attitude

produced, in my opinion, type faces that, though not wholly

adequate in the functional sense, are, as letter designs per se

(especially the capitals), unequalled as representations of classic

letter forms in print. That is their significance in the history of

type design. And it is also the reason why a close study of them is

essential for anyone who aspires to a clear understanding of

something that Van Krimpen seems not to have appreciated: the

crucial difference between art, visual expression as an end in

itself, and design, the creation of something to serve a practical

function.

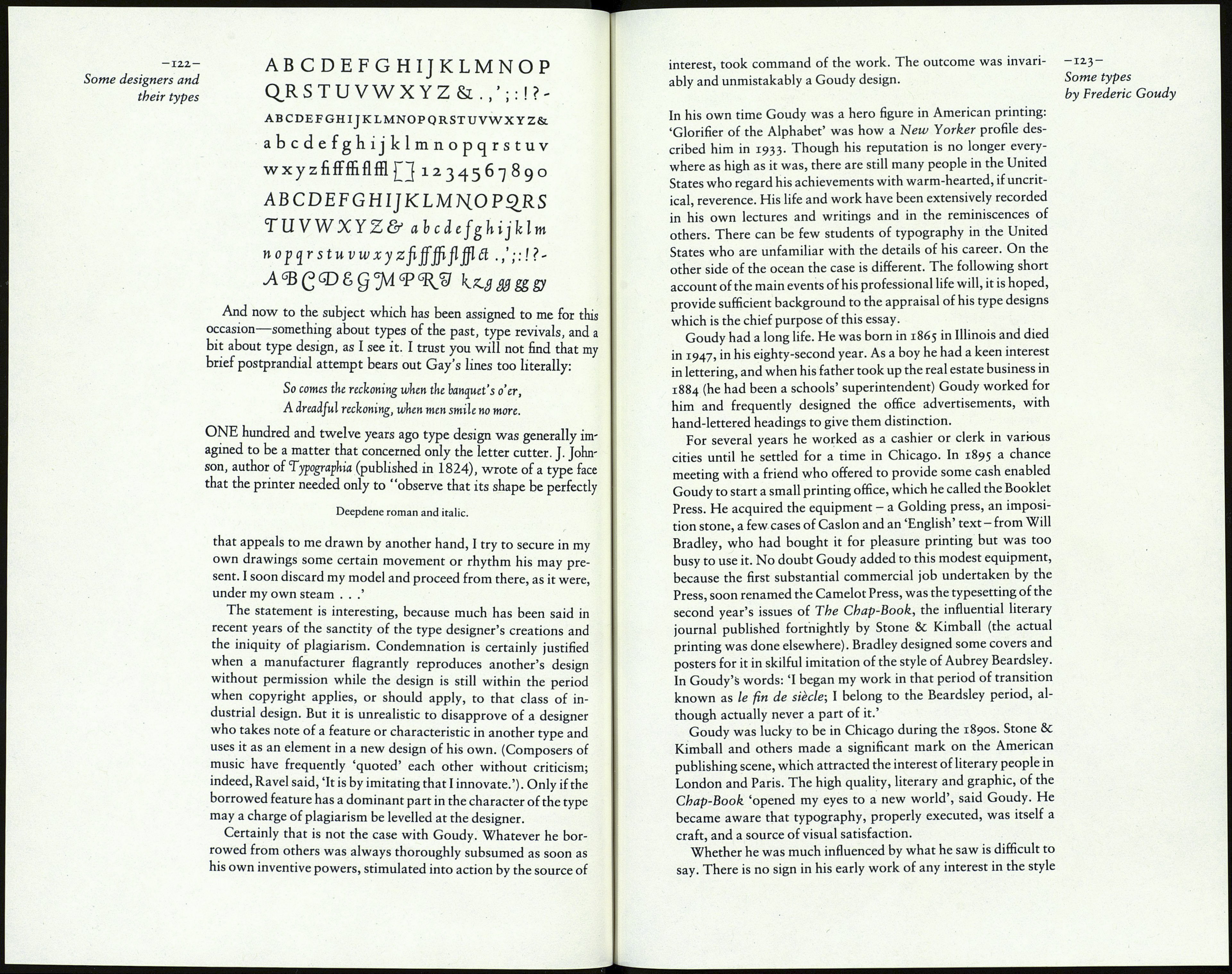

14: Some types by Frederic Goudy

'Van Krimpen's work as a book designer was more influential

than his work as a type designer.' Thus the obituary in The Times

of 21 October 1958, the day after Van Krimpen's death. True, no

doubt; but it seems that one of his types had once had an influence

on another worker in the field.

In Frederic Goudy's A Half-Century of Type Design and

Typography, he says of his Deepdene type: 'This year (1927) was

a prolific one for me. I find that I was working on six different

designs. For one of them I began drawings of a type suggested by

a Dutch type which had just been introduced into this country;

but as with some of my previous designs, I soon got away from

my exemplar to follow a line of my own.'

That passage was quoted in one of Paul Bennett's contri¬

butions to Books and Printing, with the phrase 'the Lutetia of

Van Krimpen' interpolated after 'Dutch type'. No doubt Bennett

had good reason to know that Goudy was indeed referring to

Lutetia and not, say, to De Roos's Erasmus Medieval, which had

been introduced in Holland three years before Lutetia, and may

have been known in America.

There are a few similarities between the romans of Lutetia and See overleaf

Deepdene: for example, in the shapes of C, R, c, g, r, y, z. The dots and PaBe Io:

of i and j are small and distanced from the stem of the letter in

both faces. The E and F are quite similar; but Goudy had used the

high middle bar in his Kennerley Old Style of 1911, and the broad

form of those letters can be seen in his Goudy Modern and Italian

Old Style, both earlier than Lutetia. However, the texture and

colour of Deepdene are quite different from those of Lutetia,

because the serifs and thin strokes in it are stronger than those in

Van Krimpen's type, and the serifs are unbracketed.

Deepdene Italic, which was designed in the spring of 1928,

bears no resemblance to the italic of Lutetia; in fact, Goudy wrote

of it that he 'drew each character without reference to any other

craftsman's work'. It is noticeably 'upright'; the angle can only be

about four or five degrees. Curiously, the lowercase of the italic is

remarkably similar to Van Krimpen's Romanee Italic, designed See page 10

twenty years after Deepdene.

Goudy explained his interest in the work of other designers in a

speech at Syracuse University in 1936. 'Once in a while a type face

by some other designer seems to present an interesting movement

or quality that I like. I take an early opportunity to make it mine,

frankly and openly, in the same way that a writer might use

exactly the same words as another, but by a new arrangement of

them present a new thought, a new idea, or a new subtlety of

expression ... By copying carefully a few characters of the type