In August 1861 I wrote another novel for

the Cornhill Magazine. It was a short story,

about one volume in length, and was called

The Struggles of Brown, Jones; and Robinson. In

this I attempted a style for which I certain¬

ly was not qualified, and to which I never

had again recourse. It was meant to be fun¬

ny, was full of slang, and was intended as

a satire on the ways of trade. Still I think

that there is some good fun in it, but I have

heard no one else express such an opinion.

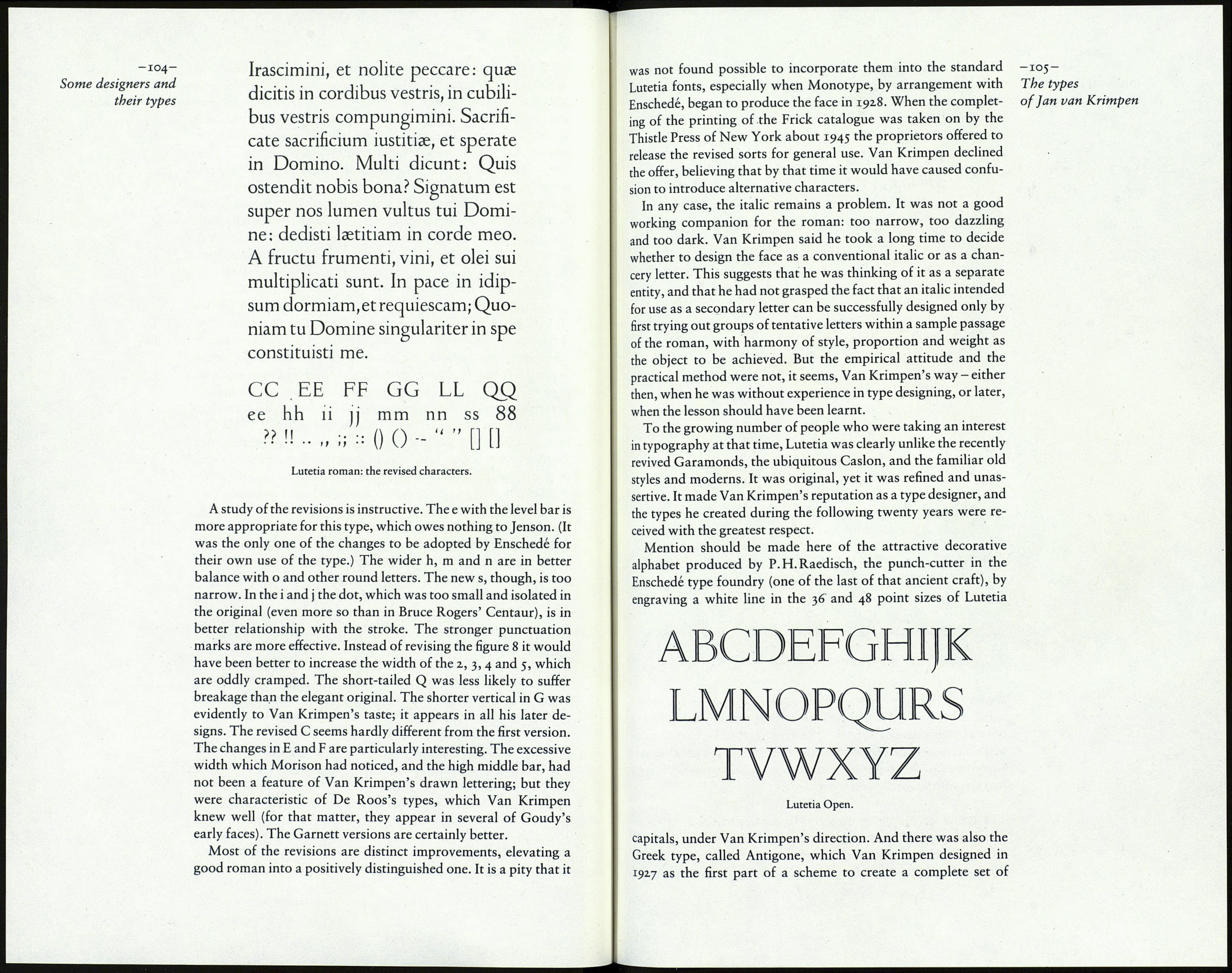

A BCD E FG H I J К LM N

О P Q^R STUVWXYZ

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

12545 fffiflffiffl 67890

ABCDEFGHIJKLMN

OPqRSTUVWX YZ

abcdejßhijkimnopqrstuvwxyz

Lutetia roman and italic. The original version.

sample, and Van Krimpen then proceeded to design the full set of

roman characters. His letter drawings were ready by the middle

of 1924, and he went on to draw the italic. The type was made

first in the 16 point size and was used in a book produced for an

exhibition in Paris in 1925: hence its name, Lutetia (the Roman

name for Paris).

In Britain the roman was reviewed in The Fleuron v in 1926 by

Stanley Morison. He observed that the type was not derived from

any historic predecessor or school, that the designer 'has kept

himself free from current English, German or American fashions'

(were there any?) and that the 'design is an exceedingly handsome

one, its proportions . . . most agreeable'. He did not care for the

e with the sloping bar, and would be pleased if the E could be

reduced a little in width. But he clearly regarded it as a remark¬

ably fine design. During the next two years the Enschedé foundry

completed seven sizes of roman capitals and lowercase, three of

titling capitals, and five sizes of italic (some of the punches being

— 102—

Some designers and

their types

cut in Germany). They were shown in an inset in The Fleuron vi -103-

in 1928, and this time the italic was reviewed. It was noted to be a The types

true 'chancery' letter, and the most legible of its kind so far; but of Jan van Krimpen

the reviewer made the comment that it is 'so good in itself that it

cannot combine, with the proper self-effacement, with its

roman'. (Presumably by 'good' he meant 'distinctive' or 'expres¬

sive'.) The Fleuron inset shows some of the swash alternative

letters made for the italic; and it must be said that they prettify the

text only at the expense of comfortable reading. Swash letters

were made for the roman, too; they can be seen in the Enschedé

specimen books of 1930 and 1932. Many years later, when Van

Krimpen wrote a survey of his type designs for The Typophiles,

he had changed his mind, and expressed disapproval of such

extraneous aids to elegance.

There was wide but not unqualified admiration for the Lutetia

design. Oliver Simon, who visited Holland in 1928 and met Van

Krimpen, ordered Lutetia for the Curwen Press. In America the

Grabhorn Press installed the type and used it frequently, though

when they tried the 18 point size for an edition of Leaves of Grass

they found the face (not surprisingly) unsuitable for Whitman's

reverberant verse. Another distinguished printer who changed

his mind was Alexander Stols of Maastricht. The Book Col¬

lector's Quarterly for July-September 1934 noted that having

composed Holbrook Jackson's Maxims on Reading in Lutetia,

Stols disliked the result and re-set the book in De Roos's Erasmus

Medieval - a type whose 'system of ornamentation' had been

criticised by Van Krimpen in The Fleuron vii as 'rather tiresome'.

The Merrymount Press had Lutetia but used it sparingly; Updike

preferred a limited typographic palette. Bruce Rogers used the 18

point for Frederic Kenyon's Ancient Books and Modern Discov¬

eries in 1927; but he did not care for the lowercase e, m and n, and

substituted for them the letters from a font of Caslon, as noted by

William Glick. This 'improving' of Lutetia was carried further by

another hand.

Porter Garnett, an expert in printing, had been in charge of the

Laboratory Press at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in

Pittsburg since 1923. The Press was awarded the task of designing

the catalogue of the Frick art collection, a monumental work of

great prestige. In 1928 Garnett visited Van Krimpen to say that he

wanted to use Lutetia for the work, but would Van Krimpen

agree to certain characters being redesigned? His published

reason was 'to amend such characters as seem to fall short of

perfection'. He may have had another reason: to tell the govern¬

ing body of the Frick collection that the type to be used in the

printing of the catalogue would be, in a sense, original. Van

Krimpen willingly agreed to the changes because, as he wrote

nearly thirty years later, they accorded with the changes he would

have made himself if it had been possible to do so.