-98- intellectual discipline. Although the sans-serif letter was no

Aspects longer held to be a fundamental article of the creed it was much

of type design favoured for its linear nature. In Britain Gill Sans was popular

until about the middle 1950s; but then - perhaps because Swiss

typographers had looked back to Die Neue Typographie and

approved of its severe view of the aesthetics of sans-serif types -

typographers developed a taste for two faces that had first been

made in Europe in the early years of this century and were then

produced by Monotype in the 1920s as Series 2.15, a face very

similar to the medium weight of the Venus type used in

Tschichold's. second book, and Series 216, its bold companion.

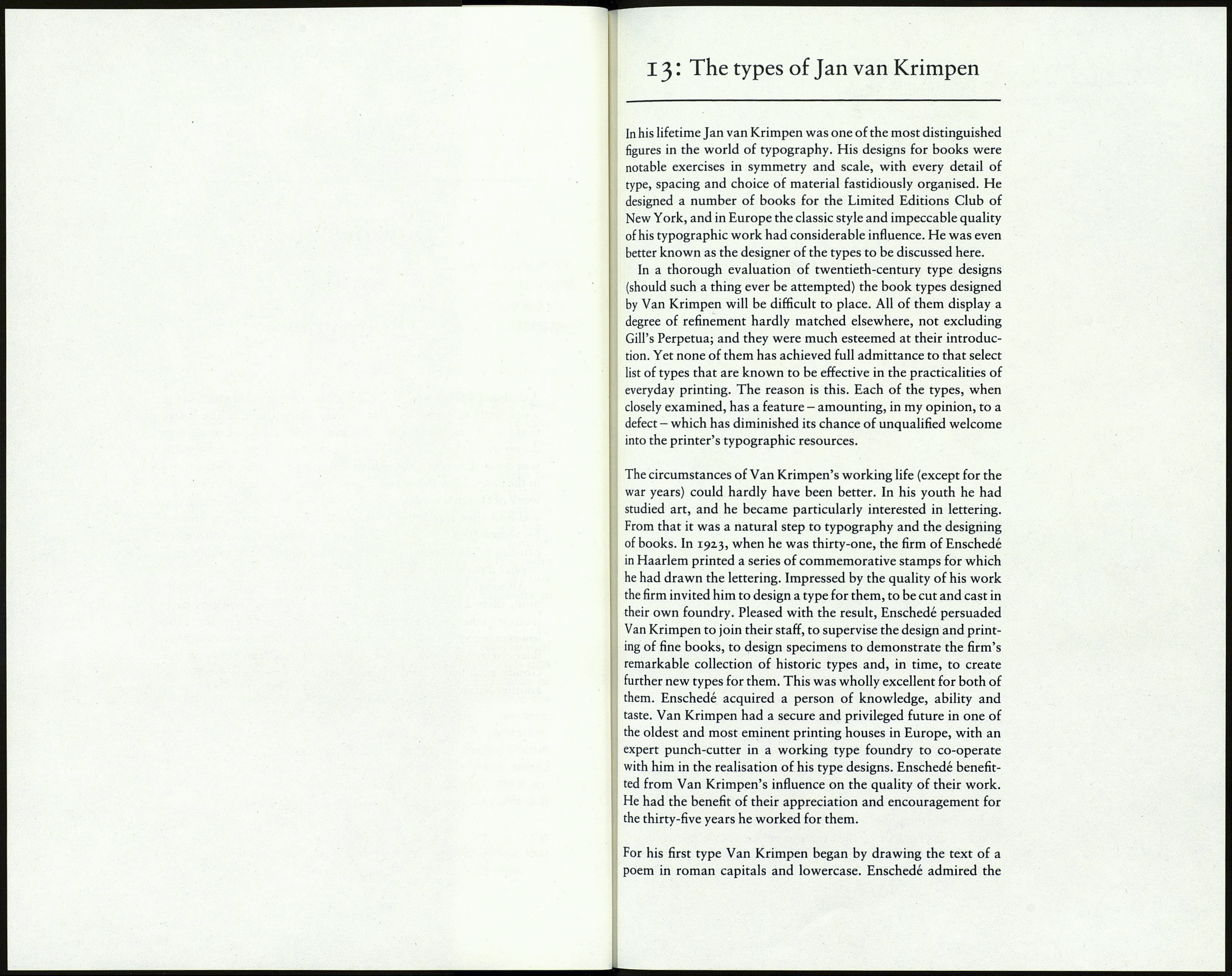

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXY2

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 123456789

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 1234567890

Monotype Series 215 and 216. American typographers will recognise them as similar to the

various Trade Gothics which at that time were brought out of

obscurity and granted the favour that they still enjoy.

These 'industrial' faces, as P. M. Handover usefully called

them, form a third species to be added to the two classes of sans-

serif already mentioned. The demand for types of this sort was

considerable. In 1957 the Haas foundry of Basle stimulated it by

redesigning one of their existing Grotesks and issuing it under the

name Helvetica. Typographers everywhere developed a consum¬

ing appetite for it. Its range of weights and widths was increased;

it was adopted by every sort of mechanical and electronic type¬

setting system; and its popularity became so great that it rivalled

the Univers sans-serif, a type of the 'industrial' class but more

original and subtle in its modelling than Helvetica and, because

its character spacing was properly done, a better performer in

text composition.

This essay has attempted no more than a sketch of the course of

events that has led to the several species of sans-serif types that

are now familiar: the original nineteenth-century grotesques or

gothics; the improved version of that style designed since the

middle of this century and called neo-grotesque or, as here,

'industrial'; the geometric faces of German source or inspiration;

and the humanist sans-serif which draws upon the classic letter

forms of the past. Only a few faces have actually been named

here, and then only because they are exemplars. In fact, the num¬

ber of sans-serif types currently available is so considerable that

any attempt at a review would certainly be invidious.

The sans-serif letter form is restricted, or apparently so, in the

scope it allows the type designer; but that is a challenge that

serious designers like to face up to at least once in their lives.

PARTII

Some designers

and

their types

A designer's attitude to his or her work is revealed as much in the

work itself as in the life, letters and relationships. In the essays

that follow, the sketch of the designer's life and times is meant to

do no more than indicate the circumstances in which the work

was done. The concentration is on the work itself- all the types

in the case of Dwiggins and Van Krimpen, a selection only of the

work of Goudy and Koch. The intention is to show their motives,

and how they responded to the tasks they were given or created

for themselves; how they observed the fundamental features of

printing types as set out in the first part of this book; and finally,

to offer a personal valuation of their achievements.

Although by character and circumstance they had little in com¬

mon, there are similarities to note. Goudy and Dwiggins each

interested themselves in substituting uncial letter forms for some

lowercase characters. Dwiggins and Van Krimpen were both in¬

fluenced by Morison's sloped roman idea. And Van Krimpen and

Goudy each acquiesced in the revision of one of their types by

another hand.