-96- might not Futura, in which the devices of geometry were em-

Aspects ployed to create 'pure' shapes, also be called 'classical', in the

of type design aesthetic sense of the word? 'Romantic', which implies the

imaginative and personal, hardly seems appropriate. On the

other hand, if Morison was taking the view that it was not very

sensible to design a type according to a theory rather than to

tradition, it could be argued that though the genesis of a type is

interesting it has nothing to do with its visual quality and its

functional efficiency.

Sans-serif faces tend to induce this kind of philosophising

about classification, merit, preference and prejudice - consider¬

ations which had exercised the mind of Jan Tschichold, another

influential figure in typography, a few years before Morison had

made his remark.

Tschichold taught typography in Munich from 1926 to 1933, the

period when the Bauhaus was active at Dessau. He was keenly

interested in the work done by the graphic designers there, and by

the typographic work produced elsewhere by El Lissitzky, Piet

Zwart and others. He formulated a doctrine of graphic design,

firmly non-traditional in its attitude, and expounded it in a book,

Die Neue Typographie, which was published in 1928. Its state¬

ment on type is particularly interesting. 'Amongst all existing

type faces only Grotesque fits spiritually into our time . . .*• The

phrase 'our time' expresses both the rejection of the artistic con¬

ventions of the past and acceptance of the influence of modern

science and technology. Tschichold's advocacy of sans-serif as

the appropriate style of letter to express the spirit of the time in

print was not a mere fancy or fashion; it was a serious and central

element in his doctrine, and it consciously elevated the sans-serif

from its former utilitarian role to a status at least equal to that of

any of the classic seriffed faces.

He went on to speak of the kind of sans-serif he had in mind.

'The existing forms of the Grotesque do not, as yet, entirely

satisfy the demands for the perfect type face . . . Most, but

especially the latest "artist-designed" Grotesques (e.g. Erbar-

Grotesk, Kabel) show modifications which fundamentally put

them in the same category as other "designed" type faces (this

makes them inferjor to the anonymous Grotesques of earlier

times) . . . One step in the right direction is the Futura designed

by Paul Renner . . .' (That last remark seems to be little more

than a politeness; it was Renner who had obtained the Munich

teaching post for Tschichold.) Tschichold's rejection of the new

'designer's' types, and his belief that only sans-serifs of an imper¬

sonal form were acceptable was demonstrated in the choice of

type for the text of Die Neue Typographie. It was a plain light-

*Quoted by kind permission of Ruari McLean from his unpublished translation

of the work deposited in the St Bride Printing Library.

weight sans-serif which since its origin in about 1909 had become

a staple jobbing type in German printing. The Handbuch der

Schriftarten shows it as being available, under various names,

including Akzidenz-Grotesk, from ten different foundries in

1926. And the text of Tschichold's second book, Eine Stunde

Druckgestaltung (1930), was set in another face of the same kind,

the Bauer foundry's Venus, which had been introduced in 1907.1

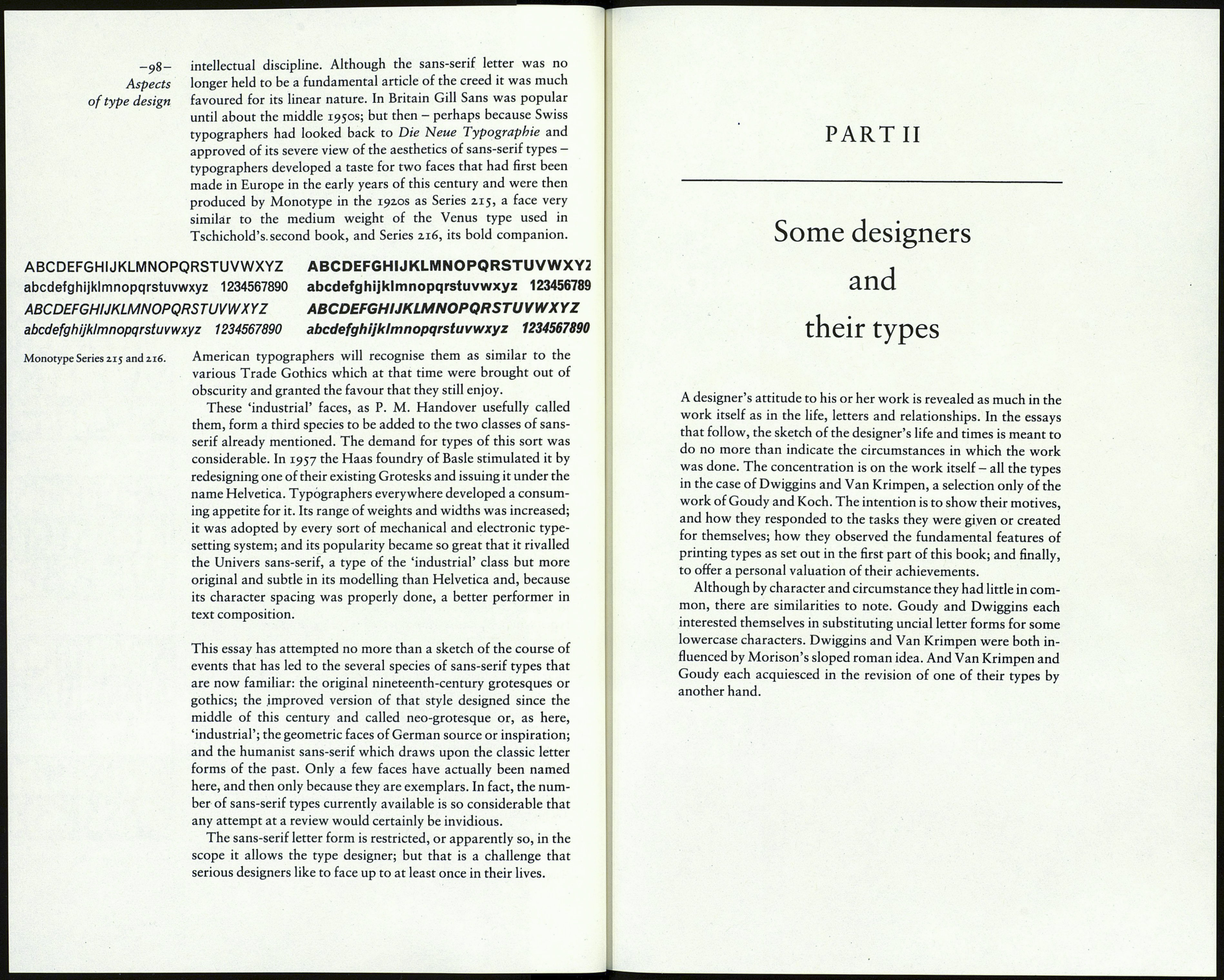

Hebrew type and its letters

Read the true experiences

LIFE IS EASIER FORYOU

think it was not so impersonal as Tschichold wished. Some of the

capitals of Venus have interesting similarities with the expressive

lettering of C.R. Mackintosh and Josef Hoffmann done a few

years before.

An English version of Eine Stunde Druckgestaltung appeared

in the July 1930 issue of Commercial Art, London, as a sort of

manifesto for the new typography. Tschichold's view of type was

now less dogmatic: '. . . it is permissible to use every traditional

and non-traditional face . . .' though he went on, 'Of the

available types, the New Typography is most partial to the 'grot-.

esque' or 'block' type . . .' His view was even more relaxed in his

third book, the Typographische Gestaltung, which was pub¬

lished in 1935 in Switzerland, to where Tschichold had moved

when the political climate in Germany had become harshly re¬

pressive. That work (the text of which was set in Bodoni, with

headings in Trump's City Medium) showed that Tschichold was

now willing to use a varied typographic palette; it included the

formal 'visiting card' style of script for purposes of contrast, and

in regard to sans-serifs did not exclude Futura and Gill Sans -

types which he had earlier rejected as possessing unwanted per¬

sonal characteristics. Indeed, there is even a criticism of the types

formerly preferred: 'The old sans-serifs are tiring to read because

their letter forms are insufficiently differentiated.'* The book was

very influential in Switzerland where, during the later 1930s and

early 40S, graphic designers perfected a style of type-and-picture

arrangement in which asymmetry, the 'grid', unjustified text and

low-voiced headings were the factors of a design formula that

produced pages of controlled rectitude. When the Second World

War ended in 1945 and people and ideas were again able to

circulate, this style of typography - called the 'Swiss' style, to

Tschichold's disapproval - was widely adopted by typographers

who, I suppose, experienced both a sense of release from conven¬

tions that had become stale and a welcome initiation into a new

*Page 89 of the English-language edition, Asymmetric Typography, 1967.

-97-

The sans-serif

Venus Light, 1907.

The straight-sided у was replaced

by the orthodox form in

exported fonts.

kVJiUM

4

мацам«

mum

тмт

Part of a poster by Josef Hoffman,

Vienna, 1905