-90-

Aspects

of type design

Some characters from Eric Gill's

first drawing for the sans-serif

type. They were revised

in manufacture.

the illustrative posters for which the transport authority was

famous (a task I sometimes had to perform at the Baynard Press —

where, incidentally, the bold version of the face, a titling, was

drawn by Charles Pickering to notes provided by Johnston in

1929). The Johnston sans-serif did not actually become type -

wooden for the sizes 6-line pica up to 36-line, metal for the 36,48

and 60 point - until about 1922, when it was needed for

letterpress-printed information notices. It was in the lower sizes

that the defects in the lowercase were liable to become visible

and, to some eyes, irritating. In the late 1970s the Johnston face

was substantially reworked by a London design studio; but

because of the variety of sans-serif types that no w compete with it

on station poster sites the type no longer has the distinction it had

when it was introduced in 1916 and made such a superior con¬

trast to the plebeian 'grotesques' of the time.

The particular attitude to the task that Johnston adopted - the

belief that the letters should be based on the classic letter forms

developed in Rome - is more significant to the student than the

type itself, which remains a 'private' design, localised in the

London area. That attitude was given further expression in a type

that was by no means 'private' and so far from being localised

actually achieved a world-wide reputation, if not popularity.

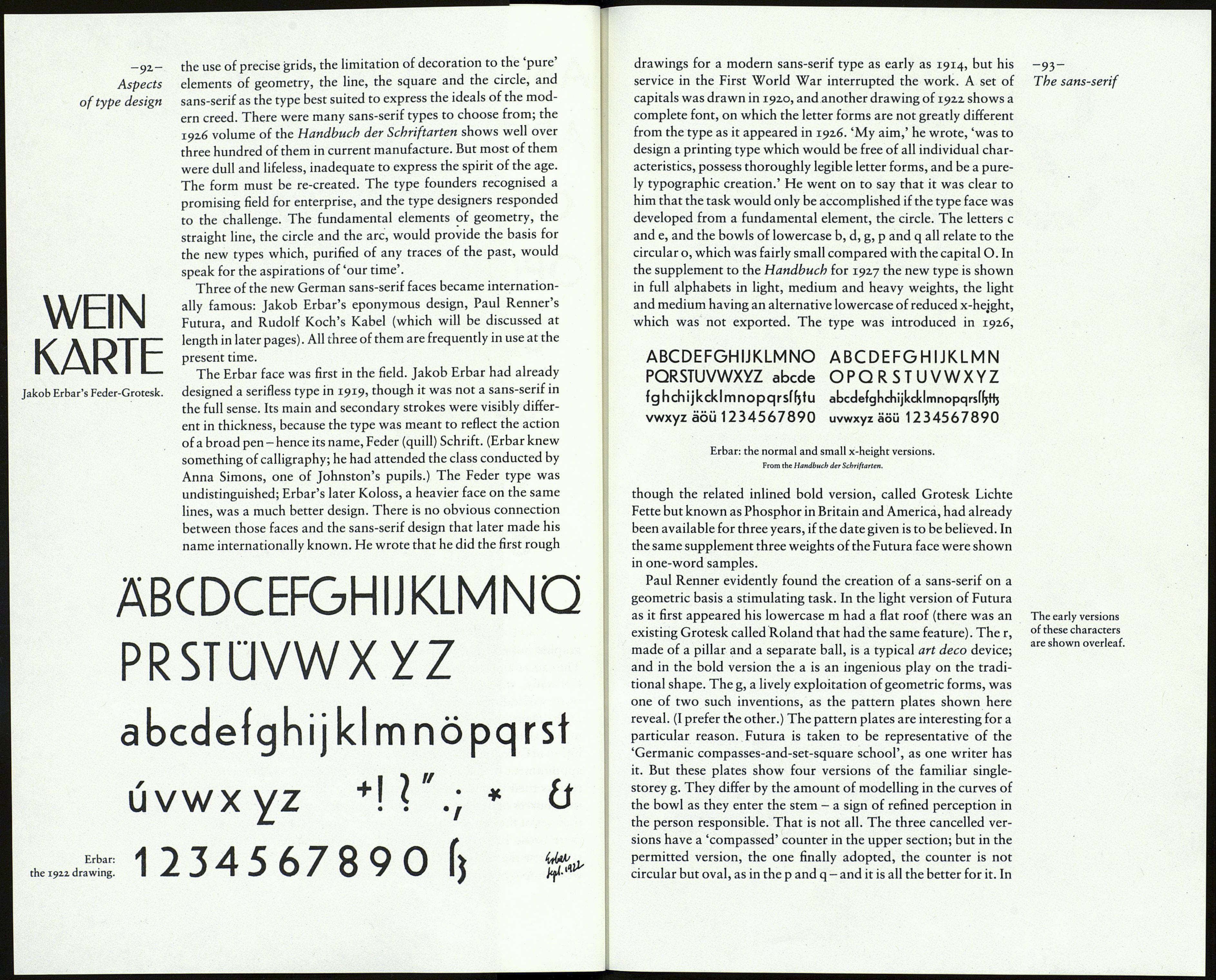

This was the sans-serif type designed for Monotype by Eric Gill,

a friend of Johnston, and introduced in 1928. Gill's original

drawing for the type contained several unusual features. There

was the flat bottom to the lowercase d (it is also present in his

Perpetua roman), a feature that was repeated at the head of p and

q. And there was the shearing of the ends of the vertical strokes at

an angle - a device we shall meet again from other hands. Those

features may have been not just personal fancies but signs of a

conscientious desire to avoid imitating the Johnston face. They

disappeared in the course of development. (The design as it fin¬

ally emerged owes a good deal to the Monotype drawing office.)

The letters and numerals of the Gill sans-serif in its basic weight

are decidedly more stylish than those of the Johnston type. The

bold version is dull; but the extra-bold deserves its popularity. Its

numerals are particularly good. In its metal form the basic Gill

Sans had one slightly unsatisfactory feature. As noted in the essay

on spacing, its fitting was a little too loose for a sans-serif. In

some filmsetting versions the character spacing has been slightly

reduced, with a consequent improvement in the texture of the

type in text sizes.

The Johnston and Gill sans-serif did not come into existence as

the outcome of an artistic movement or campaign, but were

instigated, separately, by two remarkable men: Frank Pick, the

imaginative manager of the London transport system, who com¬

missioned Johnston two years before the formation of the Design

and Industries Association; and Stanley Morison, who saw typo-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMN

ABCDEFGHIJKLMN

OPQRSTUVWXYZ

OPQRSTUVWXYZ

abcdefghijklmn

abcdefghijklmn

opqrstuvwxyz

opqrstuvwxyz

Johnston and Gill Sans compared.

graphic possibility in Gill's sans-serif lettering on a shop front.

The causes and effects of sans-serif development were different in

Germany, where as early as 1907 two important events in the

history of industrial design occurred. The first was the formation

of the Deutsche Werkbund, an association of architects, crafts¬

men and (significantly) manufacturers. It held a notable exhi¬

bition in Cologne in 1914. The second event, also in 1907, was the

appointment by A E G, the great electrical combine, of Peter Beh¬

rens as their design consultant, the first of his kind. From those

two sources of design activity, and from the non-representational

theories of the constructivist movement amongst Russian artists,

there arose in 1919, the Bauhaus, that remarkable attempt to

synthesise the values of art, craft and the machine. In its printing

workshop constructivist principles were applied to typography: