ODBEFHIJKLMN

'' и. '■ i.

PQURSTVWCG

L.

QU WA &YXZJ

NW r tfaf З^СЮюЬсоЛоййЬ^-івг^іи^^ІйСГЬп fu.) [ К .tram К» VVarovV, frfl ¿frfafr btW »Prò*

WITH CARE, INK MOT wat^roo*'.

obdcepqoyg as

aahijklmnrsek

tvwxyz ga

1234567890

oypqjyg

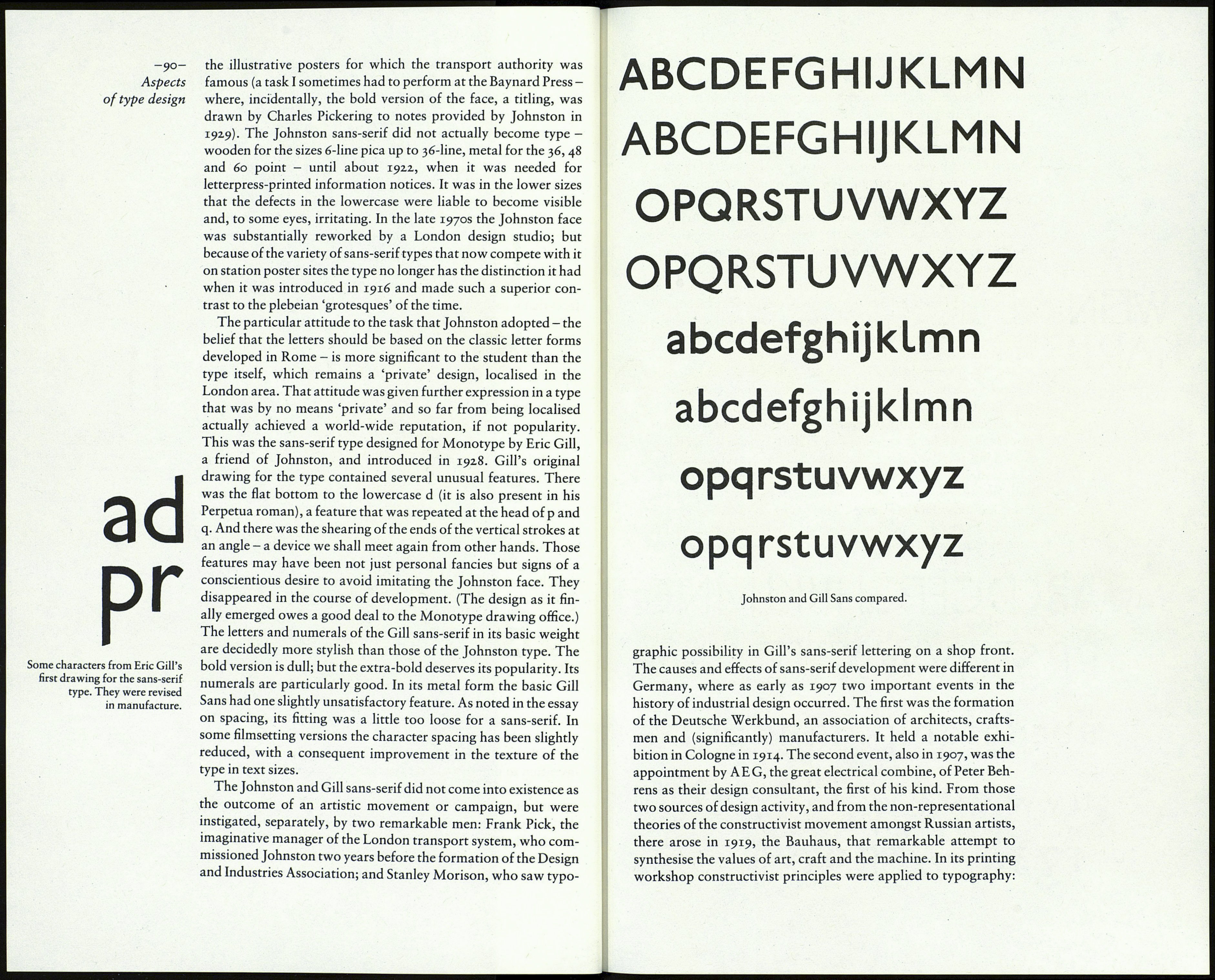

Edward Johnston's drawings of the type for the London public

transport system. Note the three versions of a and g, and the

lowered centre of w.

By permission of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

He said that his 'block' letter was based on classical Roman

capital proportions. Certainly his capitals avoid the squareness

of earlier sans-serif faces, though E and F are wider than classical

models and the short-centred M and the meat-hook S are hardly

traditional. The lowercase is a different matter. Johnston started

by deciding that the V must be circular, and he evidently thought

that the bowls of the other letters should be a section of the same

circle. (There was a good deal of 'geometry' in the capitals, too.)

The idea is reasonable, though a circle is always duller than an

oval. The widths of all the other lowercase letters related to the o.

The x-height was moderate. These proportions resulted in an

open face of ample width. (P.M.Handover was wrong to call it

'exceptionally economical'. What Johnston was given to under¬

stand was that his type was so much more legible than earlier

faces that it could be used in a smaller size with equal effect.)

Johnston established the stroke weight of the face by a method

that is natural to the professional calligrapher, for whom the size

of letters derives from the breadth of the pen. As the note on his

drawing shows, the relation of stroke thickness to capital height

was to be strictly i to 7. (Ibn Muqlah, the great calligrapher who

lived in Baghdad in the tenth century, used the same ratio in his

development and regulation of the Arabic script.) If Johnston

had studied type founders' specimen books, as he had said he

intended to do, he would probably have realised that unlike his

scriptorial work, which was an end in itself, his drawing for the

sans-serif was the means to a particular end - the manufacture of

type for printing, which meant that he was at liberty to establish

the stroke weight independently of the capital height. More im¬

portantly, Johnston should have learnt from observation of

examples of type that where curves flow into stems, in sans-serif

as well as seriffed types, the curves have to be made thinner if the

illusion of evenness is to be maintained and a clotted effect at the

joint is to be avoided. If he had been aware of that fact he might

have made his b, d, p and q better integrated, the g more graceful,

and the crotch of n and other letters more incisive.

It has been said that he took great care of the spacing of the

letters, but his tests for that purpose have not been described. If

he had tested his lowercase characters in word combinations,

with due attention to their appearance when doubled, he would

surely not have been satisfied with the gappy effect of his letter 1

(el) with its over-wide curved foot. The foot itself was a good

invention to differentiate the letter from the capital I; but it was

so broad that the letter stood aloof from the one that followed.

It might be argued that those features of the design are really

the idiosyncracies which give the type its distinctive character,

and that they had no ill effect in the large sizes in which the type

was used for its first five years or so, on station sign plates and as

litho-printed letters on paper to be pasted on to the art work of

-89-

The sans-serif

Ibn Muqlah's letter alif, to

the height of seven rhombic dots

From Y.H.Safadi,

Islamic Calligraphy (1978).