-86- only, about 20 point. It is, in fact, a type of very little value to a

Aspects jobbing printer. My guess is that the face had originally been cut,

of type design from a design supplied to the type founder, for a special order -

for a printer of labels for some sort of merchandise, say - and that

Caslon then included it in his specimen book, calling it 'Egyptian'

to suggest antiquity, in the hope that the face would take the

attention of someone else with a similar need. Evidently it did

not, because the style was not developed, either by Caslon's suc¬

cessors or their competitors, for a considerable time. My surmise,

then, is that Caslon's type was not a highly original creation by

the type founder which just happened to be ahead of its time. If

that had been the case the face would surely have been altogether

more powerful - as was, indeed, the next sans-serif type, Vincent

Figgins's, which appeared sixteen years later. (Two faces offered

by the Schelter OC Giesecke foundry of Leipzig, one of them at¬

tributed to Conner of New York, are shown in the Handbuch der

Schriftarten and dated 1825 and 1830. On stylistic grounds those

dates are about forty years too early.) Figgins's sans-serif of 1832

was heavy and large, and in the following year he had ten sizes of

sans-serif to offer. He made the style a reality, and his jobbing

printer customers must have recognised the new design as a use¬

ful running mate to the fat face and the egyptian.

Unlike the egyptian, and particularly the clarendon, which

soon assumed the role of companion to roman text faces, the

sans-serif was evidently thought of as only suitable for titling

display lines. Not until the i86"os did sans-serif types begin to

appear in the weight, width and size appropriate to text setting.

An example is the Gothic No. 4 that was shown in the catalogue

issued in 1865 by the Bruce foundry of New York. Four sizes were

available, equivalent to 6, 8, 10 and 12 point; there was a

lowercase, and the numerals were non-ranging, a clear indication

that the face was intended not only for single display lines but for

text matter in many sorts of jobbing work, though not the ex¬

tensive text settings with which we are now familiar. The use of

sans-serif for that purpose did not occur until well into the pre¬

sent century, when the process of putting words into print ceased

to be a matter for the editor or compositor with an 'artistic' touch

and became the occupation of a new specialist, the typographer.

It is noticeable that up to about 1914 the type founders had

become quite competent at producing bold condensed sans-serif

types (Stephenson Blake, for instance, had several with much

more character than any types of that sort produced since that

date), but they seemed unable to instil any quality into faces of

normal weight and width. The capitals were dull, because there

was too little variations of width. The lowercase generally lacked

the balanced proportions that had gone into the modelling of the

bold version. The letters a, g, к, r and s were often ill at ease. It

would not have troubled Bruce Rogers if the lowercase had never

arrived. Speaking in 1938 and referring to the sans-serif form he -87-

said, '. . . it has been reproduced lately in almost innumerable The sans

versions, none of them fit for the printing of books. Indeed, the

lowercase, by reason of the principle of its construction, is unfit

for reading anywhere.' Not many people would have agreed with

those last four words at that time; even fewer now. The interest¬

ing phrase in his statement is 'principle of its construction', by

which I assume he meant the common weight of all the strokes as

well as the absence of serifs. Those are in fact the two essential

characteristics of the normal sans-serif face. There are types

without serifs but with a visible difference in the weight of the

strokes; the Britannic face, designed in Britain about the turn of

the century, is an example. So are Koloss and Radiant, the dis¬

tinctive Peignot, and more recently, the excellent Optima. And

there are types of monoline stroke weight and serifs - usually

very small. The Lining or Plate Gothics (called Spartan in Britain)

are types of that sort. All of those variations of the sans-serif form

are outside the area of these present notes. It is the regular sans-

serif letter form that is under scrutiny here; and to consider how

and why it became not only acceptable as a text face but, in the

minds of some people, the only proper type for that role, it is

necessary to look at two very different lines of development in

Britain and Germany in the 1920s.

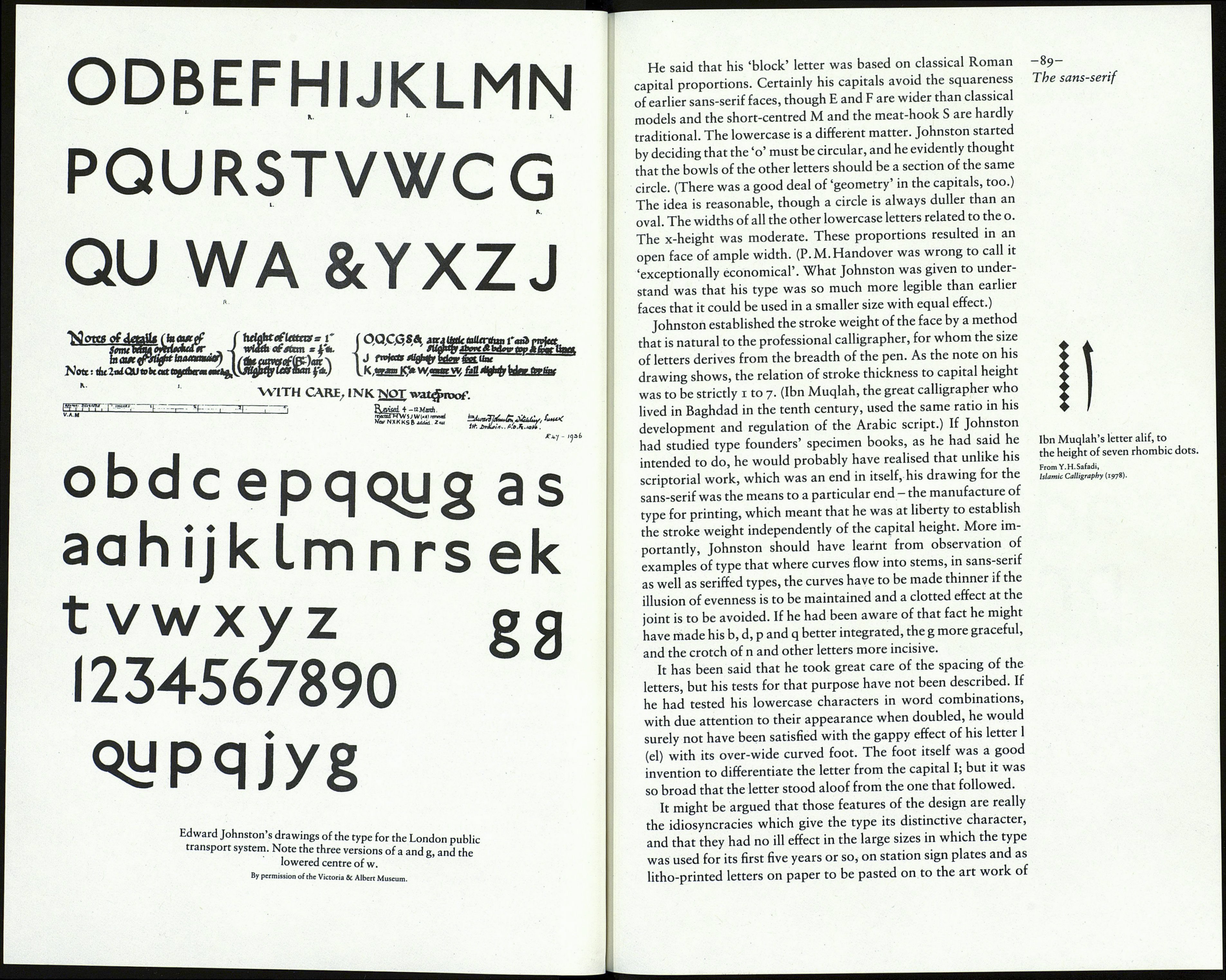

The first was Edward Johnston's sans-serif design in 1916 for

the London public transport system. In spite of its being a

'private' type, not available for general use and therefore un¬

known outside the London area, it has a place in the history of

type design for a reason that will emerge shortly. The design has

always been accorded something like reverence by writers on

typography in Britain. In 1974, when the transport authority was

in doubt as to its continuing utility and asked some of us for an

opinion, I too expressed warm respect for the original intention

and admiration for the design itself- except for a few characters

which I was then encouraged to redesign. Even so, on further

thought I find my respect for the original project intact but my

admiration for the design somewhat diminished.

Edward Johnston revived the craft of calligraphy, and in his

own work he raised the craft to the quality of art. He is still

regarded as the greatest calligrapher of the twentieth century.

Calligraphy is writing. The calligrapher writes words. He does

not draw letters. Johnston's involvement in the creation of an

italic type for the Cranach Press had been an unhappy experience

for all concerned, because, as John Dreyfus's absorbing account

of it makes clear, Johnston was temperamentally incapable of

producing letter drawings for someone else (the punch-cutter) to

translate into metal, with satisfaction to himself as well as to

others. But the sans-serif project was a task of a different sort,

which he later spoke of with great pride.