-78- with each other is crucial, not only for the rapid recognition of

Aspects words by the reader but for the regularity of texture that is essen-

o/ type design tial if the reader's comprehension is to be maintained for a long

period. Considering the amount of careful judgement that goes

into the fitting of a type face it is unfortunate, not to say absurd,

that in the 1970s some typographers, aided and abetted by trade

typesetters, developed the habit of specifying the reduction of

inter-character spacing in the text of advertising copy, with an

effect that they would have rejected if a new novel by their

favourite author had been set in the same way. The detrimental

effect on the texture of type matter could have been predicted:

emphasis of the white interiors of n, u, с and о and the white

triangles of v, w and y, but a darkening where i and 1 occurred

next to letters with vertical strokes. Nevertheless, the manufac¬

turers of electronic typesetting systems willingly became accom¬

plices in the act by producing 'advertising typesetting' computer

programs which included a selection of automatic spacing

routines, usually 'normal' (for which read 'correct'), 'tight' and

'tightest'. This use of 'minus spacing' is a spurious sort of soph¬

istication. (Typographers involved in package designing, an ac¬

tivity just as important as publicity work, seldom indulge in it, no

doubt because they are keenly aware of the need for clarity.) The

practice can only be due to a compound of ignorance and indif¬

ference. Ignorance of the process of character fitting as described

earlier is forgivable; it is an esoteric subject not part of the

typographer's normal education. But ignorance of the essential

role of character spacing has shown itself in the words of people

who should know better. For instance, there are those writers

who seem to believe that character spacing as we know it is a

mere convention and that metal type allowed no alternative -

and this in spite of Fournier's clear indication that the type foun¬

der could and would debase a type if required: 'Certain printers

occasionally ask for type thinner in set than normal, to get in

more letters to a line. This is perhaps prompted less by taste than

by economy. In these circumstances it is necessary to make the m

as thin as the extremities of the strokes will permit, so that no

shoulder remains, and to regulate the set of the other letters in

relation to it.' And there is the London typesetter who was heard

to say, 'Before the introduction of the adjustable spacing

program filmsetting looked like metal setting' - as if the printing

of the past, from Aldus and Estienne to the Elzevirs and on to

Whittingham, Rudge of Mount Vernon, the Doves Press,

Nonesuch and Curwen, to omit many, lacked a desirable but

unattainable improvement. And quite recently the manufacturer

of an electronic typesetter issued an item of print composed in a

face designed for the system, in which the colophon said, 'The

standard inter-character space has been reduced by 2 units

throughout' - as though they now thought that the fitting they

had given the face in the first place was unsatisfactory. Perhaps —79-

the naive belief that character spacing is simply a matter for Character spacing

choice is due to unthinking enthusiasm for computer programs

('the program allows choices, therefore we should use them'). No

doubt the practice of reducing the character spacing in text will

cease when typographers adopt a cool attitude towards the com¬

puter and a rational view of the qualities of readability and

legibility.

However, there is one case where inter-character space reduc¬

tion is reasonable and necessary: in a headline set from a font

actually made for text sizes. In that case a judicious closing up of

the letters improves what would otherwise be a loose and feeble

effect. It is to be hoped, though, that before long electronic type¬

setting systems will be equipped with a complete modulation

program so that all the aspects of a type - its x-height and stroke

weights and its internal as well as its external spaces - will be

automatically adjusted according to type size, so as to maintain a

proper balance of all the elements of the design.

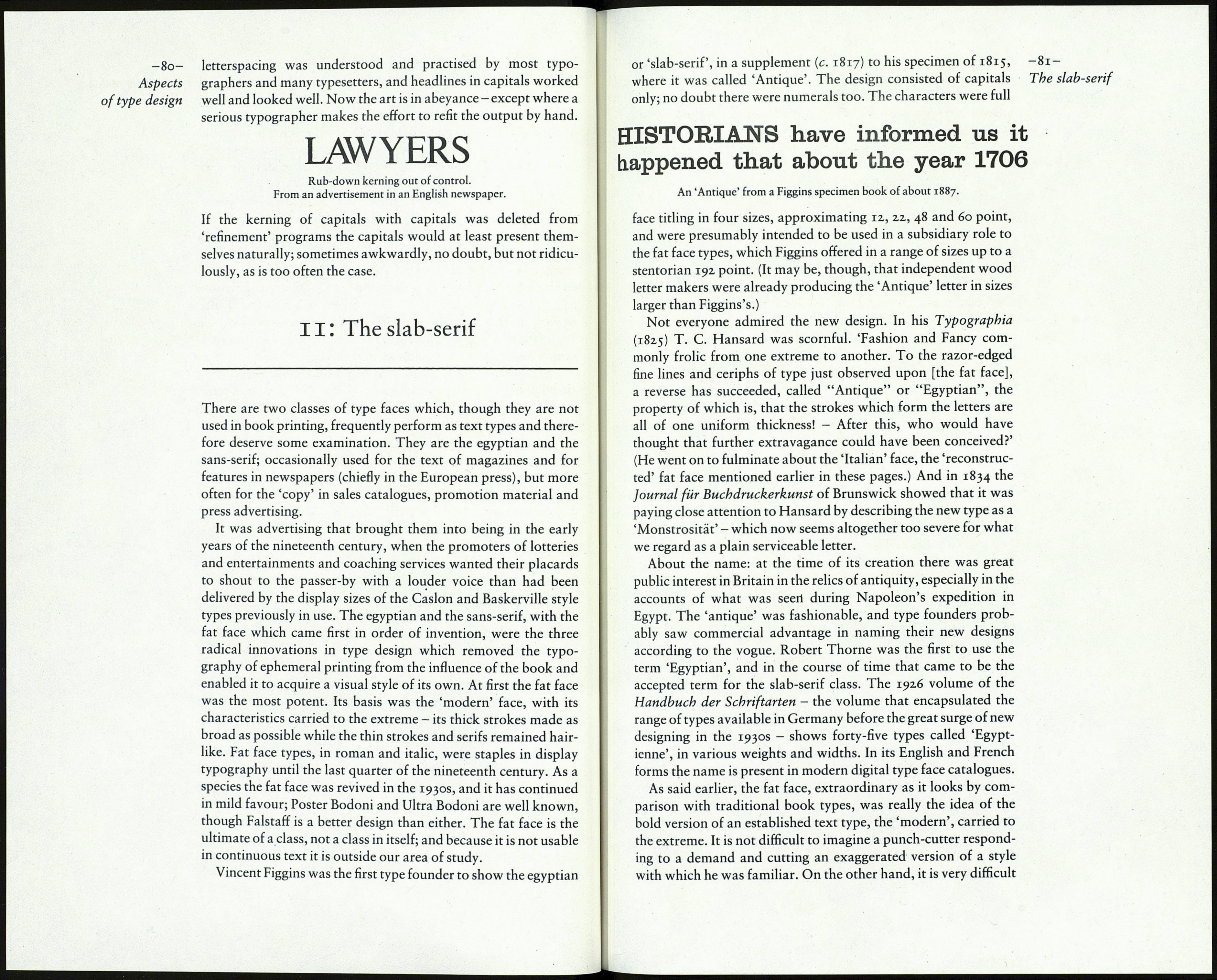

The advertising typesetting program includes one feature that

alters character fitting to its benefit - or would do so if it were

correctly organised. This is the 'kerning' routine, which allows a

letter to intrude into the 'air space' of another when the circum¬

stances make it desirable. The closing up of T, V, W and Y with

non-ascender lowercase letters is a familiar example. Unfor¬

tunately, some manufacturers have got it wrong. Too often the

program reduces the space between the letters by too much,

diminishing the identity of the letters and causing a clot of con¬

gestion. One reason for this may lie with a precedent - the

logotypes To, Tr, Ye and so on which Linotype used to make for

some of their book types. It must have been those that Bruce

Rogers had in mind when he said, '. . . the cutting [mortising] of

such letters as V and W to make them set closer than their natural

width is usually very much overdone. The new logotypes cut for

this purpose are equally faulty in this respect. The resulting effect

is more noticeable and more objectionable than the natural set¬

ting of the type would be.' If it is properly done the programmed

kerning routine can have a mildly beneficial effect on the ap¬

pearance of type in action (though thrusting the comma or period

into the angle of w or y has the contrary result). However, the

kerning of the triangular capitals A, V and W with each other

produces as many awkward effects as it cures. It improves the

appearance of the word AVAIL if the first three letters have a unit

or two subtracted from the space between them; but the same

process will have a bad effect in AVILA, because of the two

uprights in the middle of the word and the unalterable white area

in LA. There is only one reliable way to balance capitals with

each other: it is to add space between them according to their

shapes. Not so long ago, in the days of metal type, the art of visual