-72- characters, was content to say, in a letter to Stanley Morison

Aspects about a proof of trials of Perpetua roman, 'The space between

of type design letters wants alteration, but as you say, that can be done inde¬

pendently of me.' (Barker, Stanley Morison, p. 233.) Reynolds

Stone, another accomplished letter-cutter, left the fitting of his

Minerva design to the Linotype drawing office staff at Altrin-

cham. The fitting of the types designed by W. A. Dwiggins was

dealt with by the Linotype office in New York, under the direc¬

tion of С H. Griffith; but at least Dwiggins took an interest in the

process. In his WAD to RR, written in response to Rudolph

Ruzicka's request for advice on type designing, he said, 'Each

type letter, wherever it goes, carries along with it two fixed blank

spaces, one on each side. And of course, each one of the 26 is

likely to be placed alongside any one of the other 25 with their

fixed blank spaces ... the letter shapes occur in groups of

similars: when you have solved for n alongside of n you are close

to a workout for h i j 1 m and for the stem sides ofbdkpq-a

proper fitting for о gives you a line on the round shapes . . . a, c,

e, on their open sides, and f g r t are hard to fit . . .' He went on to

say, 'There isn't any fitting formula worked out yet. G. [Griffith]

says there can't be any: that it is a job for the eye alone. I have a

hunch that a "coarse" formula could be worked out, because

there is certainly a "right" interval for a given weight and height

of stem, varying as these dimensions vary'.

Griffith was right in his belief that the eye is the final judge of

character spacing; but Dwiggins was also right to suspect that the

fitting process could be expressed in the form of a system, a

combination of formula and optical judgement - though I have

never seen such a system described in print. The one that follows

is based on the principles I learnt from Harry Smith of Linotype

over thirty years ago. I have found it reliable, and I think Dwig¬

gins would have accepted it.

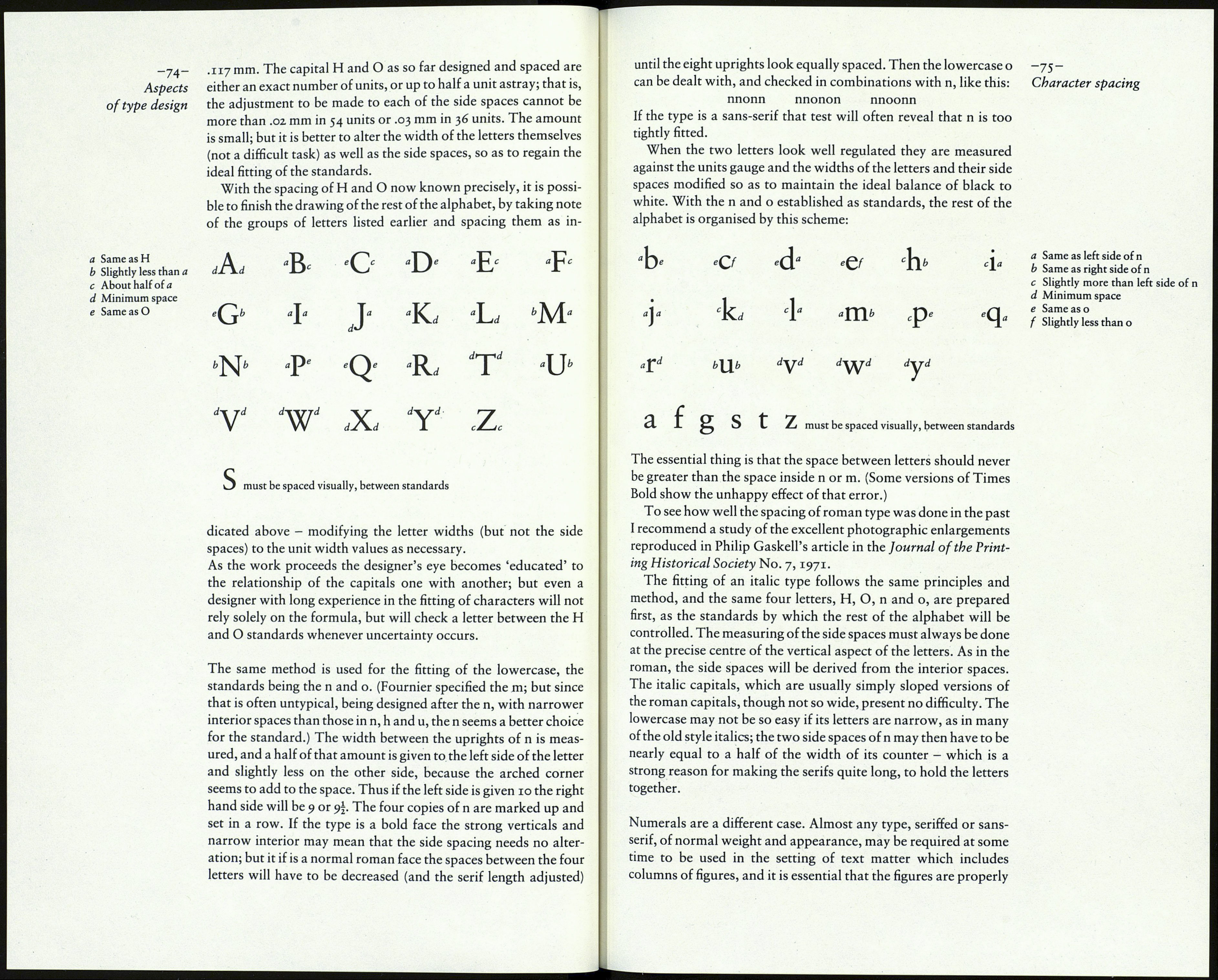

In the roman alphabets, capital and lowercase, most of the letters

are formed of straight strokes or round strokes, or a combination

of them; and the direction of emphasis is vertical. The letters can

be grouped like this:

letters with a straight upright stroke:

BDEFHIJKLMNPRU bdhi j к 1 m n pqr u

letters with a round stroke:

CDGOPQ bcdeopq

triangular letters

AVWXY vwxy

the odd ones:

STZ afgstz

The fitting of the alphabets is best done when the letters have

been sketched but before they are 'finished', because the fit¬

ting process may require adjustments of the character widths,

especially if they are to conform to a prescribed unit system. _73_

For the spacing of the capitals the basis is the H. The designer Character spacing

will have tested it with a few other letters and satisfied himself

that the weight of its strokes, the width of its interior space,

and the shape and length of its serifs are all in accord with his

purpose. Four black-on-white copies of the H are needed. The

width between the uprights of the letter is measured and half that

amount is marked on each side of the letter on all four copies.

When they are set together in a row, their eight upright strokes

are equally spaced. That spacing will probably look correct if the

type is a bold face, the verticals emphatic and the counters nar¬

row; but for faces which have strokes of normal weight and fairly

broad interior whites - ordinary text faces, in fact — the crossbar

of H acts as a ligament drawing the uprights together, so the side

spaces must be reduced until they look equal to the interior

spaces. Creating this illusion is a task for the eye and careful

judgement (a reducing glass is a useful aid). Time is needed to get

the balance right. It is time well spent, because much depends on

it. The length of the serifs must not be a controlling factor; they

must be shortened as necessary. The spatial relationship of the

verticals is the important thing.

The serifs at the four corners of H make a linking effect with

adjacent letters. Because they are absent in a sans-serif type the

side-spaces of a sans-serif H have to be narrower than those in a

seriffed face.

When the four Hs look harmonious, the spaces between them

not too open, not too cramped, the distance between them is

measured. A half of the amount is now the appropriate alloca¬

tion for each side of H, and for all other capitals having a straight

vertical stroke.

The next letter to deal with is O, of which two copies are

needed. One copy is placed between two pairs of correctly-

spaced Hs, and the spaces on each side of it are reduced or

increased until all five letters seem to be in balance. The space is

then measured. The amount belonging to H is subtracted, and

the remainder is therefore the amount due to O. But another test

is needed. The two copies of О are marked with the side space

just arrived at, and are placed side by side between the two pairs

of Hs, thus, HHOOHH. This test may show the need to revise

the fitting of О - and even the H, because it is a new test of that

character too. When that has been done the process has reached

the stage when the ideal spacing of the two most useful capitals,

the 'standards', has been achieved.

At this stage, and not before, the letters must be adjusted to the

unit system (if there is one) of the typesetting machine for which

the type is intended. A unit system finer than 54 to the em will

require little or no change in the side spacing. At 54 units at 12

point size the unit is .078 mm. In the 36 unit system the unit is