-50- decision being made, the baseline became a permanent and un-

Aspects changeable feature of the system; it is common to all type faces

of type design supplied by that manufacturer, and all functions, such as the

placement of sized-down font numerals in the role of superior

figures, are measured from it. With their considerable library of

existing letter drawings to call upon Linotype chose to use their

traditional standard alignments of the hot-metal era: 8,12 and 18

point alignments where an existing type was available in display

as well as text sizes. New designs were made to the standard 12

point alignment only, whatever range of sizes it was to be used in

- a doubtful practice. Other manufacturers made choices to suit

themselves - some of them to unfortunate effect on the propor¬

tions of their types, to judge from the evidence to be seen too

often on the booksellers' shelves.

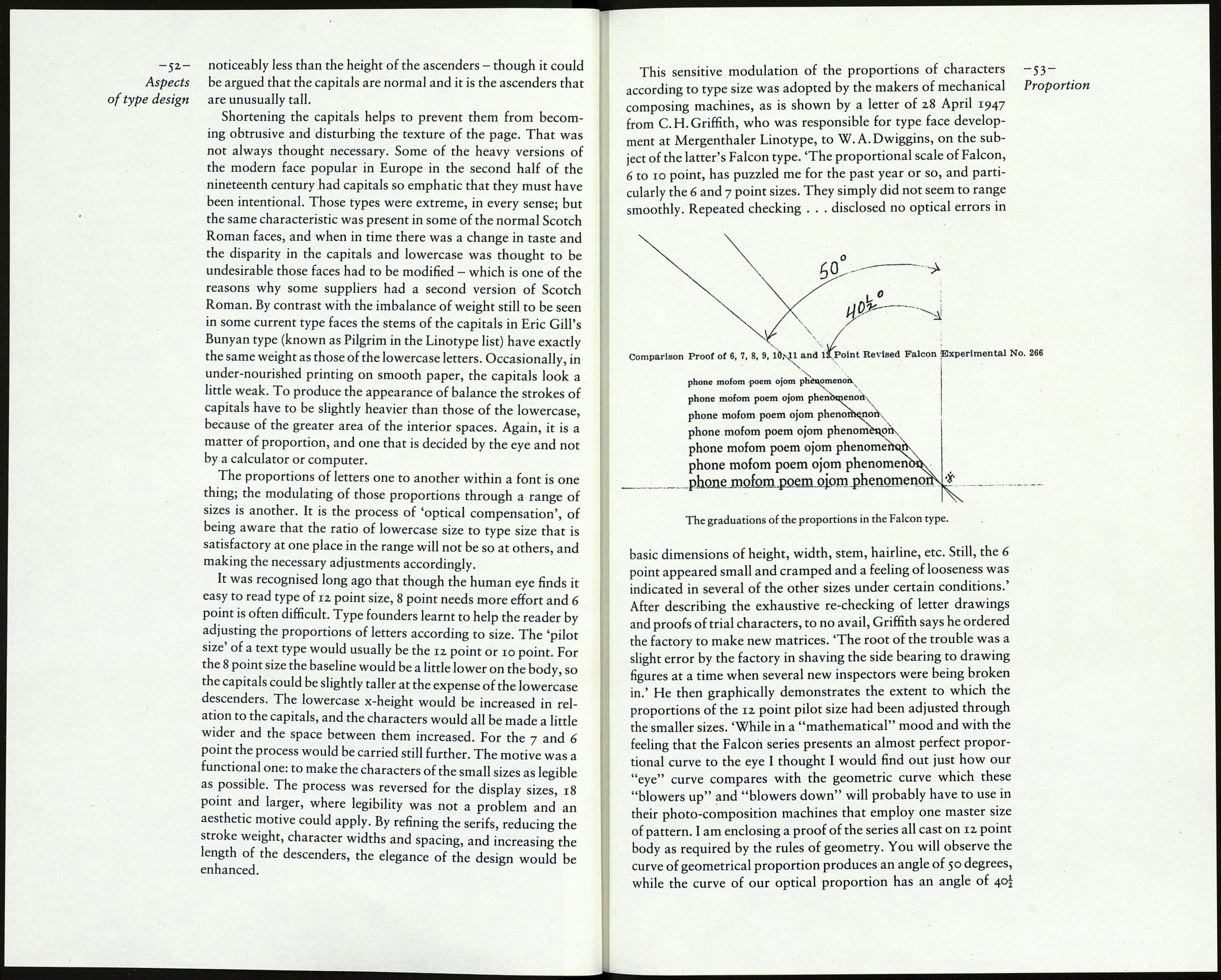

The length of the descenders is only one aspect of the proportions

of a type design and, in regard to readability, not the most im¬

portant. If the descenders are short the appearance of the letters

g, j, p, q and y may be displeasing to the professional eye, but the

reader's comprehension of the text will not suffer much. The

case is otherwise with the ascender elements in b, d, h, к and 1

which, if they are shortened, cause the letters to lose some of their

individuality and the words in which they occur to lose some

of their familiar shape. Actually, though, ascenders are seldom

shortened - certainly not when the baseline is fixed. When ascen¬

ders seem to be short it is usually because the x-height is larger

than normal. An extreme example is the Antique Olive sans-

serif type; an attractive face when used in a display line but not

very legible or readable when used in advertising text matter - a

consideration that evidently does not trouble some typographers.

The ratio of x-height to ascender height is an important fac¬

tor in the style, and the quality, of a type. Francis Meynell's

'Nonesuch Plantin', which was Monotype Plantin no with the

ascenders lengthened as well as the descenders, transformed the

type to a remarkable degree, making it look not only more refined

but as if it derived from another period: Fournier's, say, not

It was a delightful occasion, and began one of my most treasured

friendships, which did not end until B.R.'s death in 1957. I

found his personality a complete confirmation of his work as a

typographer. His line of talk was as firmly gende as his drawing of

a border or typeface. He was a propagandist but he was kind; he

admired a great tradition and showed how one could adapt it to

modern use; he treated the young aspirant as a fellow-worker.

The lengthened ascenders and descenders in Monotype Plantin no,

as used in the text of Sir Francis Meynell's autobiography My Lives.

The n point size of Monotype Baskerville was similarly treated.

Granjon's. For my own taste, if x to h is a proportion of about six

to ten a face will look refined and be pleasant to read. If the x-

height is much less than that the face may be stylish but will be

unsuitable for a long text. A larger x-height conduces to dullness.

Small x-height was a characteristic of types produced in the first

quarter of this century; see, for instance, Goudy's Pabst Roman,

the charming Nicolas Cochin, and the popular Astrée of the

1920s. A more notable example is Cheltenham Old Style, the first

size of which, the 11 point, was made in November 1900. The

design is always credited to the architect Bertram Goodhue,

though Ingalls Kimball of the Cheltenham Press may have direct¬

ed it. The insensitive modelling of the face was partly redeemed

by the small x-height, which gave the type a degree of refinement.

The recent large x-height version has eliminated even that small

virtue. It is not the only type of the past to have been tastelessly re-

proportioned by latter-day design studios.

The height of the capitals compared with the lowercase ascen¬

ders is another vertical relationship that has an effect on the

appearance and quality of a type. The accepted opinion now is

that in a type designed for book printing the capitals should be

shorter than the ascenders. The amount of the difference in

height has varied from one face to another. In Poliphilus, Bembo

and Garamond the difference is clearly visible. In eighteenth-

century faces such as Caslon, Fournier and Baskerville the

capitals are nearly as tall as the ascenders. (At Francis Meynell's

request Monotype made shortened capitals for Fournier 185 for

use in the first Nonesuch Shakespeare.) Trump Medieval, a type

of comparatively recent origin, has capitals that are unusually

short - a characteristic favoured in Germany, no doubt, where

the printed language uses capitals very frequently.

In sans-serif types 'short' capitals seldom occur. An interesting

exception is Tempo, the Ludlow design, which was popular in

British newspapers for many years. In the light, medium and bold

versions (but not the heavy weight) the height of the capitals is

The basic character in a type design is determined

by the uniform design characteristics of all letters

in the alphabet. However, this alone does not

determine the standard of the type face and the

quality of composition set with it. The appearance

The basic character in a type design is determined

by the uniform design characteristics of all letters

in the alphabet. However, this alone does not

determine the standard of the type face and the

quality of composition set with it. The appearance

Linotype Ionic was the progenitor of several faces, including

Textype, shown here. The type size is the same, and there is hardly

any change in the size of the capitals. The distinct difference in

appearance is due to the lowercase x-height.

-51-

Proportion

Simone Hats are

extremely unusual in

that they combine a

noticeable Elegance of

Style and a Superior

Quality. Fifty Years

of Experience goes a

long way toward the

making of such Hats.

SIMONE

MADISON STREET

The original Cheltenham

Old Style, as shown in the

November 1904 number

of the ATF American

Cbap-Book.