-22- put up with what they could get. In France, where the trade was

Aspects encouraged by patronage, it was possible for printers to express

of type design annoyance at the fact that type sizes were not always the same

from one foundry to another, and that there was no reliable

correlation between one size and the next.

An attempt to remedy this state of things by official decree was

made in Paris in 1723, when in a set of regulations on the conduct

of printers and booksellers there was included a rule that type

founders were to make their type body sizes to a prescribed sys¬

tem of relationships. It was one thing to make regulations; it was

another thing for a type founder to alter his 'standards', such as

they were, and so risk damage to the continuity of his business.

But for a man setting up in the profession de novo there was no

obstacle. It was Pierre Simon Fournier's decision in 1737, when

he was 25, to do just that - to start on his own, to cut his own

punches and make his own matrices and even his own moulds.

He thus created an opportunity to give reality to the regulations

of 1723 - though in regard to the relationship of body sizes he did

it on his own terms.

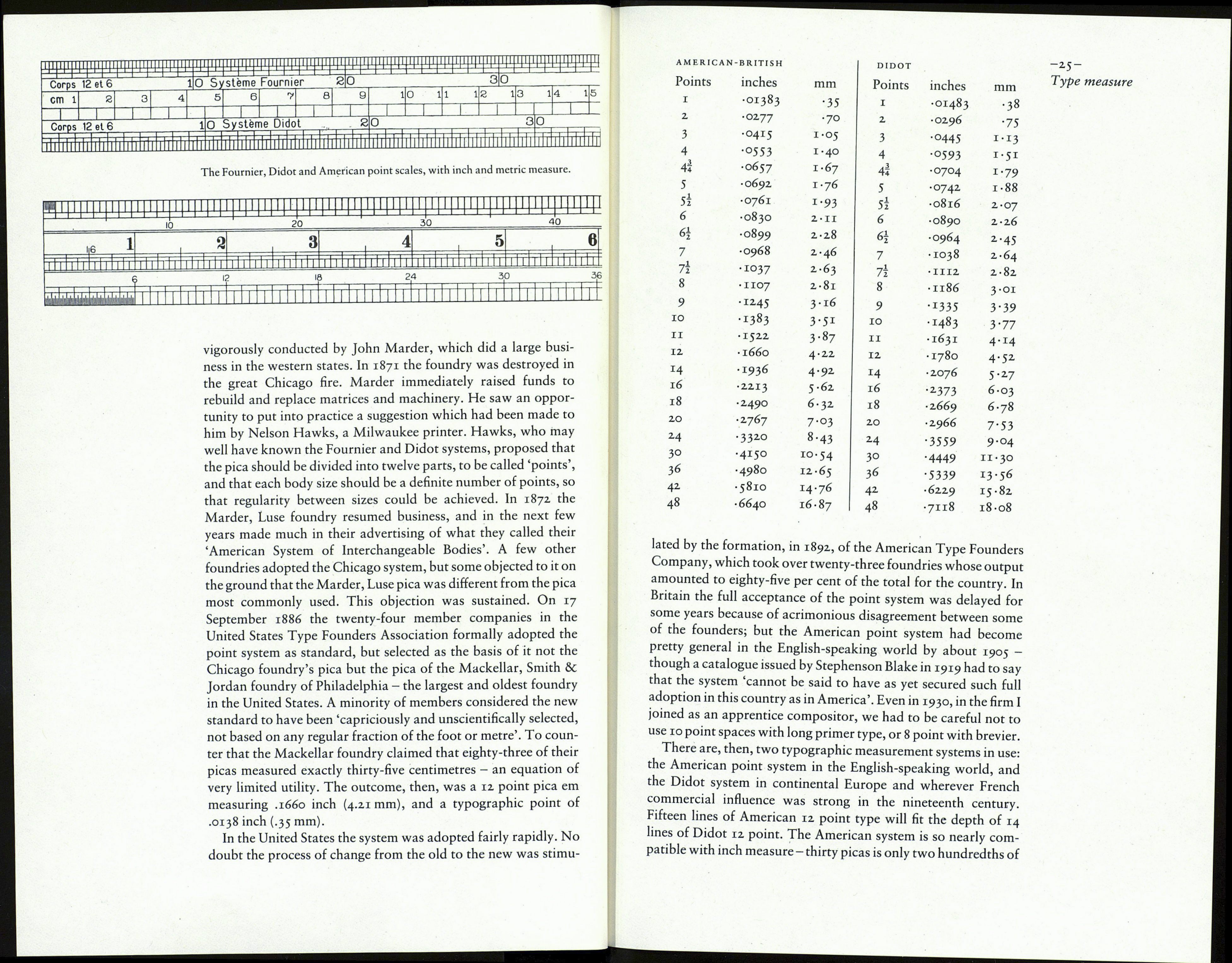

Fournier's system was simple enough. Using the familiar ter¬

minology of linear measurement he set up a scale of two 'inches'

{pouces), divided these into twelve parts {lignes) and each part

into six points. All the usual body sizes were to be made to a

stated number of these 'typographic' points: nonpareil was 6

points, petit-texte was 8 points, cicero 12 points, and so on for the

twenty type sizes he envisaged. The use of a definite base made it

possible to fix a definite relationship between sizes.

Fournier's pouce, ligne and point were not precisely of the

same dimensions as the divisions of those names in the French

'foot' (which itself at that time varied from one area to another).

It is probable that Fournier thought it commercially prudent to

produce body sizes not greatly different from those in common

use.

The obvious advantages to the printer in a system of sizes

which had a definite relationship to each other were widely rec¬

ognised, and Fournier's great innovation was adopted through¬

out France and the Netherlands during his lifetime. But after

Fournier's death in 1768 the wind began to blow from another

direction.

The great Didot family began its rise to eminence in printing in

the middle of the eighteenth century when François Didot, a

successful publisher and bookseller, added printing to his other

activities. He was joined by his son François-Ambroise who, by

the excellence of his work, gained a notable reputation. About

1775 he started a type foundry as an adjunct to his printing office,

and it was presumably then that he decided to revise the Fournier

point system by making it directly relative to the official linear

measure, the French 'foot' and its normal subdivisions. This was

praiseworthy and logical, no doubt, and in accord with the spirit -23-

of the age of reason. But it resulted in a unit larger than Type measure

Fournier's: the Didot point is .0148 inch (.38 mm), while the

Fournier point was about .0135 inch (.34 mm).

The introduction of the Didot system was not universally ac¬

claimed. There were those who found the 'largeness' of the Didot

sizes too much of a departure from tradition to be tolerable; and

there were others who, having adopted the Fournier system,

disliked the thought of changing to the new one. But the great

reputation of the Didot family - especially when the sons of

François-Ambroise, Firmin the punch-cutter and Pierre the

printer, achieved prominence in the 'classic' movement in typo¬

graphical design - overcame opposition to the new point system,

and it rapidly gained favour. And then logic defeated logic.

In 1791 an official committee was set up to devise a new system

of weights and measures; in 1795 its terminology was established;

and in 1801 the metric system was given legal status (one of the

notable reforms of the French revolution). It thus obliterated the

one advantage that had been claimed for the Didot point system

in comparison with Fournier's - compatibility between the

measurement of type, particularly in page width and depth, and

the measurement of paper and other materials of printing. The

annoyance this caused to printers could not be assuaged - the

Didot point system was too solidly established. Indeed, in the

course of the nineteenth century it extended itself throughout

Europe and beyond, wherever French influence was dominant.

Although Firmin Didot made an attempt in 1811 to revise the

system instituted by his father so as to bring it into relation with

metric measure, nothing came of it. The Continental printer was

obliged to accept the fact that the typographic point and the

metre, however unrelated, were here to stay.

These energetic (if unfortunate) efforts by French type foun¬

ders aroused little interest among their counterparts in Britain.

Though Johnson and Hansard, in their respective Typographias

of 1824 and 1825, refer to the need for regularity in type sizes,

they have nothing to say about the reforms of Fournier and

Didot. The first mention of either seems to have been made in

1841, in Savage's Dictionary of the Art of Printing, which de¬

scribes Fournier's system at length. Although there was a grow¬

ing desire for some sort of regularity - a desire which increased in

the United States as the number of foundries multiplied - it was

not until T. L. De Vinne began writing for Caslon's Circular in

1878 that American printers gave serious attention to the French

systems.

The origin of the American point system has been described on

more than one occasion - not always accurately. The system was

first adopted by Marder, Luse & Co., the Chicago type foundry