-202- would probably have noticed and corrected the dropped shoul-

Some designers and der of capital B. On the drawing the serifs of the letters are

their types elegant; but the drawing being about twenty-two times larger

than the final type size, they are much too thin for reduction to 9

point, and the Monotype draughtsmen must have had to

strengthen them considerably. In fact, the design process in¬

cluded a great deal of trial manufacture; many punches and

matrices were scrapped and remade 'on account of errors in en¬

graving [there cannot have been many of those - the Monotype

workmen were very skilful] or second thoughts on the part of the

designer'. This supports the view that Morison did not begin

with a clear vision of the ultimate type, but felt his way along, so

to speak. As to his second thoughts: although, as Allen Hutt

remarked, Morison was no draughtsman, he was quite capable

of expressing the revisions he needed in the form of sketches; and

if he did so it was those, perhaps, that he was thinking of when he

wrote his account of the gestation of the type in A Tally of Types.

The number of reçut punches was 1,075, a figure often men¬

tioned, presumably as evidence of the earnestness that went into

the work, though it is also evidence of an inability to make effect¬

ive decisions at the drawing stage. The figure is large; but a pos¬

it may be claimed that The Times, with its new

titling, its new device, and its new text types,

possesses, from the headline on the front page to

the tail imprint on the back, a visual unity. But

this is no more than the beginning of typographical

wisdom, for visual harmony, whatever its signi¬

ficance for the artist, has little value for the general

reader unless and until it accompanies the basic

factors of textual legibility. The reader needs a

definite plainness and familiarity of type design;

It may be claimed that The Times, with its new titling, its

new device, and its new text types, possesses, from the

headline on the front page to the tail imprint on the back,

a visual unity. But this is no more than the beginning of

typographical wisdom, for visual harmony, whatever its

significance for the artist, has little value for the general

reader unless and until it accompanies the basic factors of

textual legibility. The reader needs a definite plainness and

familiarity of type design; the greatest possible size and

clearness of impression ; and that adjustment of the

spacing, first, to the single letters, next to their combina¬

tion in words, lines, paragraphs, columns, and pages which

makes the whole "look right" to him. From this point of

It may be claimed that The Times, with its new titling, its new device,

and its new lext types, possesses, from the headline on the front page

to the tail imprint on the back, a visual unity. But this is no more than

the beginning of typographical wisdom, for visual harmony, whatever

its significance for the artist, has little value for the general reader

unless and until it accompanies the basic factors of textual legibility.

The reader needs a definite plainness and familiarity of type design ;

the greatest possible size and clearness of impression; and that

adjustment of the spacing, first, to the single letters, next to their

combination in words, lines, paragraphs, columns, and pages which

niakes the whole "look right" to him. From this point of view what,

if anything, was wrong with the founts which served until yesterday?

Were the types wrongly designed, or were they wrongly used?

All the current newspaper types—the so-called "moderns"—are

designed upon a century-old model ; the former type of The Times

was no exception to this rule, although it was much the best of its

kind. But English craftsmen have come to lead the world in all that

belongs to the design and printing of books, by studying the art of

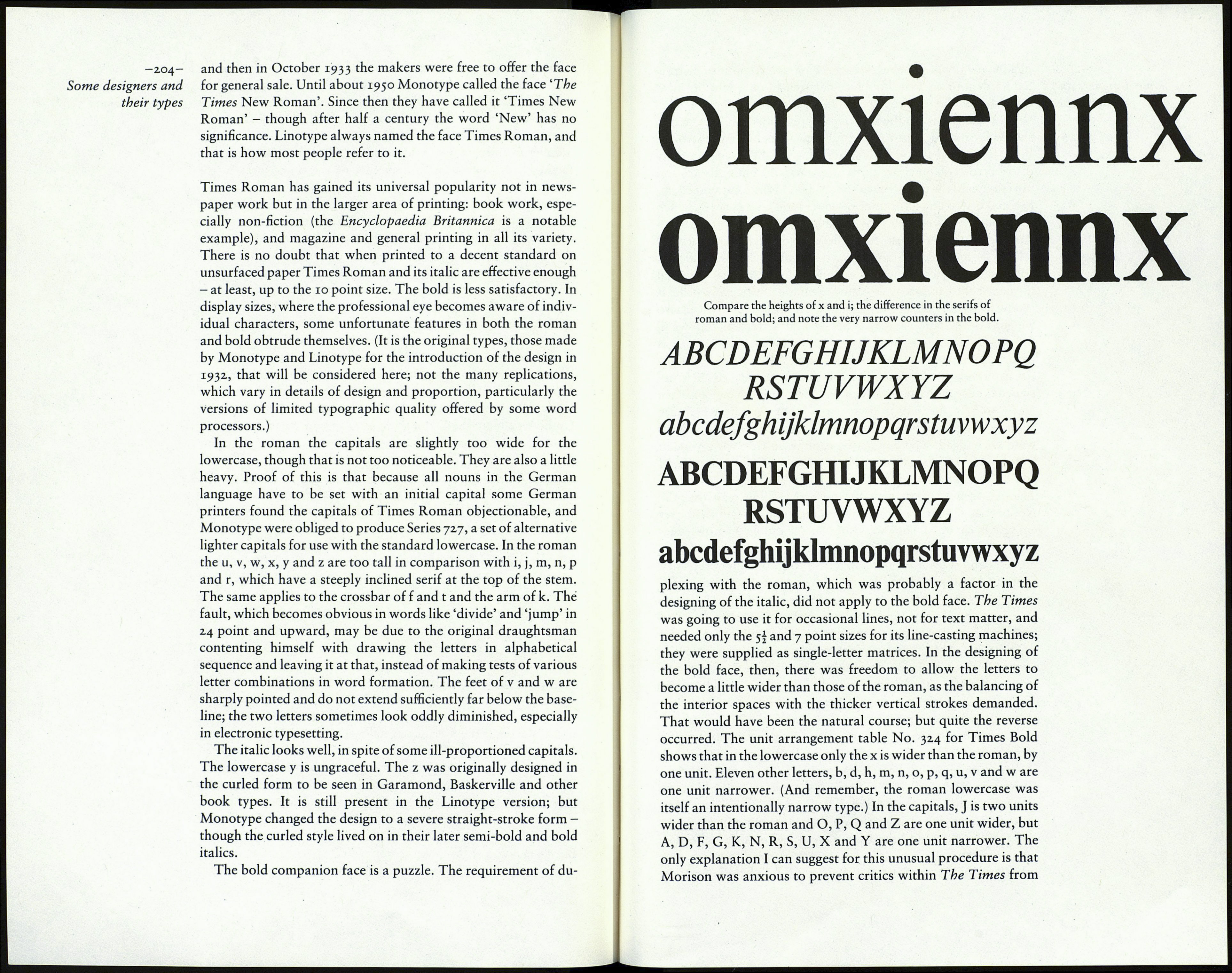

The design was created for three essential sizes:

9,7 and 5^ point.

sible explanation is that several sizes of the faces were already in -203 -

manufacture when proofs were being studied. For example: the 7 Stanley Morison's

and 5I point roman were actually put in hand for punch-cutting Times Roman

only five days after the 9 point was proofed. The revision of a

letter in the 9 point would affect the other two sizes, and the

number of rejected punches would multiply. The same process

might have occurred in the making of the other faces in the

family.

Early in June 1931 sample drawings and cast type of the roman

were supplied to Linotype, who were to make the matrices for the

linecasting machines which were used at that time to compose

the bulk of the paper. By the end of the year the paper's compos¬

ing room had been furnished with matrices of the text sizes, and it

probably also had Monotype matrices of the heading types (it is

curious that Linotype did not begin work on the heading faces

until August 1932, only two months before the new types publicly

replaced the old). For most of 1932 the date of the change-over

was undecided, partly because of editorial preoccupation with

the effects on the country of the economic depression and the

formation of the coalition government, but chiefly because of

internal disagreement about Morison's proposal that the paper's

Gothic title piece should be changed to roman. But by 3 October

1932 all was resolved. On that day The Times appeared in its new

typographic dress, to general admiration.

Something else was new on that momentous day. 'A make of

paper, newly manufactured according to a formula for express¬

ing the new fount to best advantage, has simultaneously been

introduced to serve it.' Anyone who consults the files of The

Times of the 1930s will immediately be aware of its high standard

of printing, made possible by the journal's comparatively small

circulation and the quality of the paper, heavier and far more

opaque than present-day newsprint. That the quality of the paper

was significant in the effectiveness of Times Roman as a news¬

paper type was shown in 1956 when, for reasons of economy, a

lighter weight of paper was adopted, with a smoother surface (in

aid of the famous half-page picture at the back). This made the

text type look sadly feeble; so on Morison's advice the text size,

which by then was 8 point, was changed to 8 point cast on j\

point, the descenders being specially shortened. This deliberate

reduction of the inter-line white space strengthened the overall

colour of the text, but gave it a disagreeable clotted appearance.

The practice was abandoned later. It is evidence of the fact that as

a newspaper type Times Roman lacked the physique for produc¬

tion conditions less favourable than those enjoyed by The Times

in the 1930s - a fact always more obvious to American than to

British newspaper production managers.

For a year The Times retained the sole right to use the type,