ital A into a circle. Make sure that you

try all the possibilities you can imagine.

New ideas or at least new points of view

will surface during the process. Choose

the best sketches and draw them more

carefully at a larger scale —about 7 in¬

ches (15 to 20 centimeters) high. Now

check to see if a photographic reduction

to У% inch (5 millimeters) still renders

clear details.

Lettering in a Circle

Sometimes you may want a circular ar¬

rangement of letters. To balance the

amount of text with the diameter of the

circle, it may be preferable to arrange

short texts in two semicircles. Capitals

usually work best, because they create a

more pronounced ribbon effect.

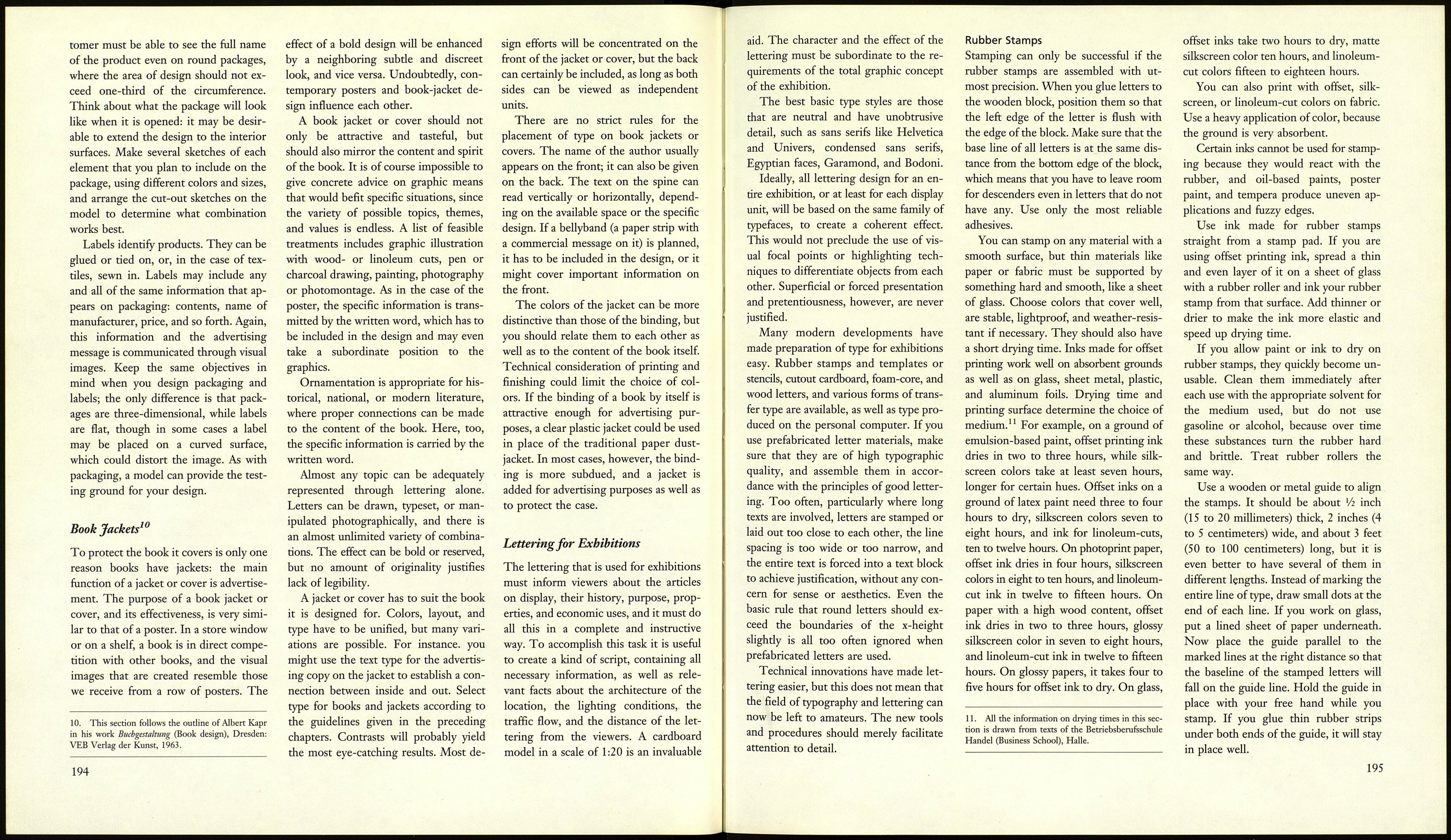

Figures 415 through 418 illustrate the

process of arranging the letters in circu¬

lar fashion. Start with rough sketches to

establish the relationship between letter

size and diameter of the circle. Include a

border in the design. When you have

decided on one design, multiply the

inner diameter of the circle by 3.14 (pi)

to determine the length of the letter

strip (Figure 416). On this strip make a

sketch and then a more detailed drawing

of the lettering. Transfer it onto the

middle line of the ring (Figure 417). Di¬

viding the text into an upper and lower

section will make it easier to read.

Posters

Most posters combine pictures with

words. The lettering carries the specific

message, but it is an integral design ele¬

ment and visually subordinate to the pic¬

ture. Most graphic artists lack the training

to design letters, and prefer to incorpo¬

rate copies of established models into

their work: their decisions are thereby

limited to choosing type and determin¬

ing its size and placement on the poster.

Alternatively, the lettering could be

developed from the style of the image.

Here the words would not act as a con¬

trasting element, but rather as part of an

integrated design. (See for example the

Figure 415

poster in Figure 498, page 225, which

did not require a knowledge of formal

letter construction.)

In some posters the letters are the

sole transmitter of meaning — that is, the

text is the visual image. Handled in mas¬

terly fashion, the effect can be quite

impressive. Some topics do not lend

themselves to graphic depiction and are

actually better served by such treatment.

Typographic, handlettered, or even three-

dimensional letters can be used and

manipulated, and many combinations

are possible. The rich diversity of con¬

tent must be expressed through various

representations of letters. A word or a

group of lines simply formed by adding

one letter to the other can surprise, and

possess a decidedly monumental look.

Posters aim to transmit ideas, which

may have cultural, educational, political,

or other meaning. Unless the poster is

displayed indoors only, it has to com¬

pete — on billboards and walls, for exam¬

ple—with a host of other materials for

the attention of the viewer. Since it is

Figure 416

FUR ML =[>

i imi i 111___________________________________________________________

Figure 417 Figure 418

192

impossible to predict what the eventual

surroundings of a poster will be, the de¬

signer is obliged to search for ever novel

and interesting layouts. It should be

noted here that it is not necessarily the

most extroverted and gaudy image that

draws the most attention, but sometimes

the simple and serene.

A poster designed to be hung out¬

doors has to be visible for a distance of

about 10 to 15 yards (10 to 15 meters)

to attract attention and interest. Its

drawing point might be an expressive

quality, a feeling of movement up and

down or back and forth, the emotional

content of its colors, its intensity, or even

its aggressiveness. Whatever the design,

it must create quick associations in the

viewer to involve him or her emotion¬

ally. Big closed forms with interesting

details in the interior serve the purpose

best, because they are visible from afar

and still provide interest for the nearby

observer.

A poster persuades by making its

main message clear, and it is obvious

that the words here are as important as

the formal design. The central idea must

be accessible quickly and without great

effort, but this does not in any way pre¬

clude the inclusion of secondary mes¬

sages that linger in the mind of the

viewer for some time or become obvious

only after repeated encounters.

To get started designing a poster: jot

down ideas with pencil or colored pen¬

cils, then clarify important aspects such

as size and weight relationships and

color in small-scale sketches. Compare

sketches of various elements in different

sizes, stroke widths, and colors, and try

out various arrangement of the cut-out

pieces until the result is pleasing. Check

to be sure that effects planned in the

sketch format work when enlarged to

poster size.

If the poster contains a lot of text,

break it into blocks. Even ih a poster

made up entirely of text, certain sections

can be planned as preworked units, to be

replaced as necessary. For example, al¬

ternate information on the location of an

event can be set on an overlay, to be

placed in the appropriate position by the

printer.

Packaging and Labels

A product wrapper simultaneously pro¬

tects, advertises, and informs purchasers

about content and quality. Buyers usu¬

ally transfer the impressions they get

from the package to the product itself. It

is therefore obvious that the packaging

should produce positive associations.

Color, quality of material, and design

are the key features to which the con¬

sumer responds.

The packaging designer needs not

only technical skills, but also a certain

knowledge of psychology. The designer

has to be able to predict buyers' reac¬

tions, as well as convey information

about the product. A can of cocoa must

not resemble a paint can; toothpaste and

skin-lotion containers have to be dis¬

tinctly different.

The most important function of pack¬

aging is to characterize the product

through visual elements — images, deco¬

ration, and lettering—all of which have

to be integrated in the completed de¬

sign. Type, photographs, and illustration

can be combined. If the main element of

design is the lettering itself, the orna¬

mental values of the letters have to be

explored for their aesthetic impact, but

the wish to create something original

must never interfere with the legibility

of the text.

It may be necessary to include some

or all of the following data on a package:

contents, name of the manufacturer,

price, weight or piece count, logo or

trademark, governmental notices, ingre¬

dients, and assembly instructions. This

information should be clear and easy to

understand. Some of it, such as assembly

instructions, recipes, or a list of parts,

can also be given on the inside of flaps,

or on a separate sheet of paper or

brochure inserted in the package.

The graphic elements chosen must

serve to distinguish the product from

others to avoid confusion between simi¬

lar products, but possess a recognizable

style that is common to all products of

the particular company. This can be ac¬

complished by using the same lettering

style on all printed matter, including the

company logo and its signage. A unify¬

ing color or combination of colors can

serve the same purpose. Entire families

of product designs can be created in this

way. Some companies or products are

already well known and associated with

a particular image or tradition. It is wise

to continue such traditions if they are at

all acceptable from the designer's point

of view.

It is essential to consider the available

materials for packaging and the ways in

which they can be manipulated. Paper,

cardboard, metal foils, vinyl, glass,

wood, and sheet metal all have distinctly

different characteristics, and react differ¬

ently to print or other means of decora¬

tion. Other important considerations for

package design include: economic fac¬

tors and special requirements for hand¬

ling, storage, and shipping, but these can¬

not be discussed in the limited space of

this book.

Packaging is three-dimensional, and

it is imperative to make full-size models

to account for possible technical prob¬

lems. Consider different views and an¬

gles of the finished product and position

graphic elements accordingly. Boxes

should present the intended view from

at least two opposite sides, and the cus-

193