Adhesive Binding. Adhesive-bound books

are held together not by sewing but by

a special glue. Adhesive binding is com¬

monly used for soft-cover books, but is

equally useful for larger handwritten

books, because the sheets can be ar¬

ranged with the fold towards the out¬

side, as described above. The pages open

more freely in this style, but the book

should be assembled by a bookbinder,

and it will not be as durable as a conven¬

tionally bound book.

Covers for One or Two Signatures. A board

cover is easily fashioned. You must

crease the board parallel to the grain di¬

rection in the middle of the board and

sew or glue the signature into it. If you

are gluing the signature, you must score

two more lines parallel to the middle

fold of the board, one on each side, at a

distance of У% inch (5 millimeters) from

the fold, so the book will open easily

(Figure 408). Paper can be folded

around the board cover and held in place

by means of flaps that reach almost back

to the fold (Figure 409). If you use this

method, which is known as English

binding, it is not necessary to attach the

first and last pages to the cover—just

put them under the flaps. The wrapper

can reach as far back as the inner edge

of the cover and can be made of printed,

marbled, or otherwise decorated paper.

It carries the title either in written form

or on a label.

When you score board for a booklet

of two signatures, you must take the

width of the spine into account (Figure

410). Apply adhesive to the cover, insert

the signatures, and weight the book be¬

tween two wooden boards until the glue

is dry. Depending on the size and thick¬

ness of the block, you may need to at¬

tach the endpapers to the cover with

adhesive, or you may just tuck them

under the paper wrapper, as described

190

above. Usually the latter is sufficient.

Should you desire a traditional hard¬

cover binding, consult a hand bookbinder.

It remains your responsibility to make

suggestions for the design and to choose

the materials.

We have covered only a limited

amount of information about paper, cov¬

ers, and techniques of binding. The

graphic artist who wishes to know more

can consult Franz Zeier's Books, Boxes,

and Portfolios (New York: Design Press,

1990) and other sources.

Lettering in Applied Graphic Art

Logotypes

A logotype is an expression of the essen¬

tial substance of a particular company,

institution, or organization, of an idea, a

special occasion, or a product. Logos are

visual signs, and their form comes from

the object they depict or from related as¬

sociations. Geometric or natural forms

can inspire logotype designs — for exam¬

ple, the environment could be sym¬

bolized by a stylized leaf. Other sources

are scientific symbols, heraldic forms, or

visual representations of the word in

question. The locality of a subject might

be important enough to be pictured.

Purely naturalistic forms, however, are

rarely effective.

A logo can also be developed from a

company's initials or the name of the

product. Logos that are made up of let¬

ters, monograms, and lettering of any

kind demand the same treatment as pic¬

torial symbols. There must be contrast

and tension. Interior space and spaces

between shapes carry as much weight as

the shapes themselves, and all the

graphic elements have to form a unit. A

logo should be more than a conglomera¬

tion of unrelated elements that are held

Figure 405

Figure 406

Figure 407

Figure 408

crease to facilitate opening

Figure 409

W ^ creases for

Vdouble fold Figure 410

Figure 411

together by a border. The examples in

Chapter 5 illustrate this principle.

It is, of course, possible to combine

letters and pictorial elements in a single

logo. Certain letters provoke associa¬

tions such as a feeling of lightness or

weight. Use these associations as well as

any other emotional messages the forms

may carry.

The following principles apply for all

logos, pictorial or based on letters:

A logo must be easily recognizable; it

has to be simple and memorable.

The purpose of the logo should influ¬

ence its form.

Most graphic forms of advertisement

are based on or include the logo of the

subject; the logo usually appears on let¬

terheads, brochures, labels, packaging,

and delivery vans. It may be necessary to

render it in varied materials, such as

cardboard, plaster, glass, metal, fabric,

or even neon. The technical require¬

ments and restrictions of work in any of

these materials must be taken into con¬

sideration from the earliest stages of de¬

sign, since it is obvious that printing,

embossing, punching, casting, or weav¬

ing require distinctly different approaches.

Variations may be necessary if the same

logo is to be executed in techniques as

different as engraving in steel or model¬

ing in plaster. It is rare, however, that

one design has to fit such diverse require¬

ments; more commonly it is enough to

satisfy the following requirements.

All details should still be visible if the

logo is reduced to Уъ inch (5 millime¬

ters). Unlimited enlargement should be

possible, though a variation of stroke

thickness might be necessary for very

large versions.

The logo has to be reproducible in

black and white and positive or negative,

and it is useful if a representation in sev¬

eral colors is programmed into the design,

but it is rarely feasible to concentrate on

color exclusively. It has to stand on its

own as well as fit into a frame. Consider

the possibility of relief or freestanding

sculpture.

Logos are protected by law. A new

design must be original and may not

create associations with already existing

ones. The simpler the design, the harder

to avoid this problem.

Logos are subject to fashion. The

taste of the public changes in the field of

graphic art almost as quickly as when it

comes to hem lengths. Since the logo is

an essential element of all graphic design

pertaining to a product, it should be

changed only if absolutely necessary,

and then only gradually, especially if old

and established products are concerned.

Some logos are developed from the

name of a product or a company. The

letterforms should be chosen in relation

to the particular product or company;

the letters must form a word that stands

on its own as a composition, and the

word must stand out among other text

elements. Again, the design must be easy

to remember.

To ensure that the word can be read

easily, the letterforms must never be

modified beyond their basic characteris¬

tics. Figures 412 and 413 show examples

of design that sacrificed legibility to the

visual image in a misguided attempt to

be original. Unfortunately, many similar

examples could be cited.

Logos may be executed with pen or

brush as well as with type, but the field

of application is more limited, because

calligraphic forms cannot be transferred

so easily to other media.

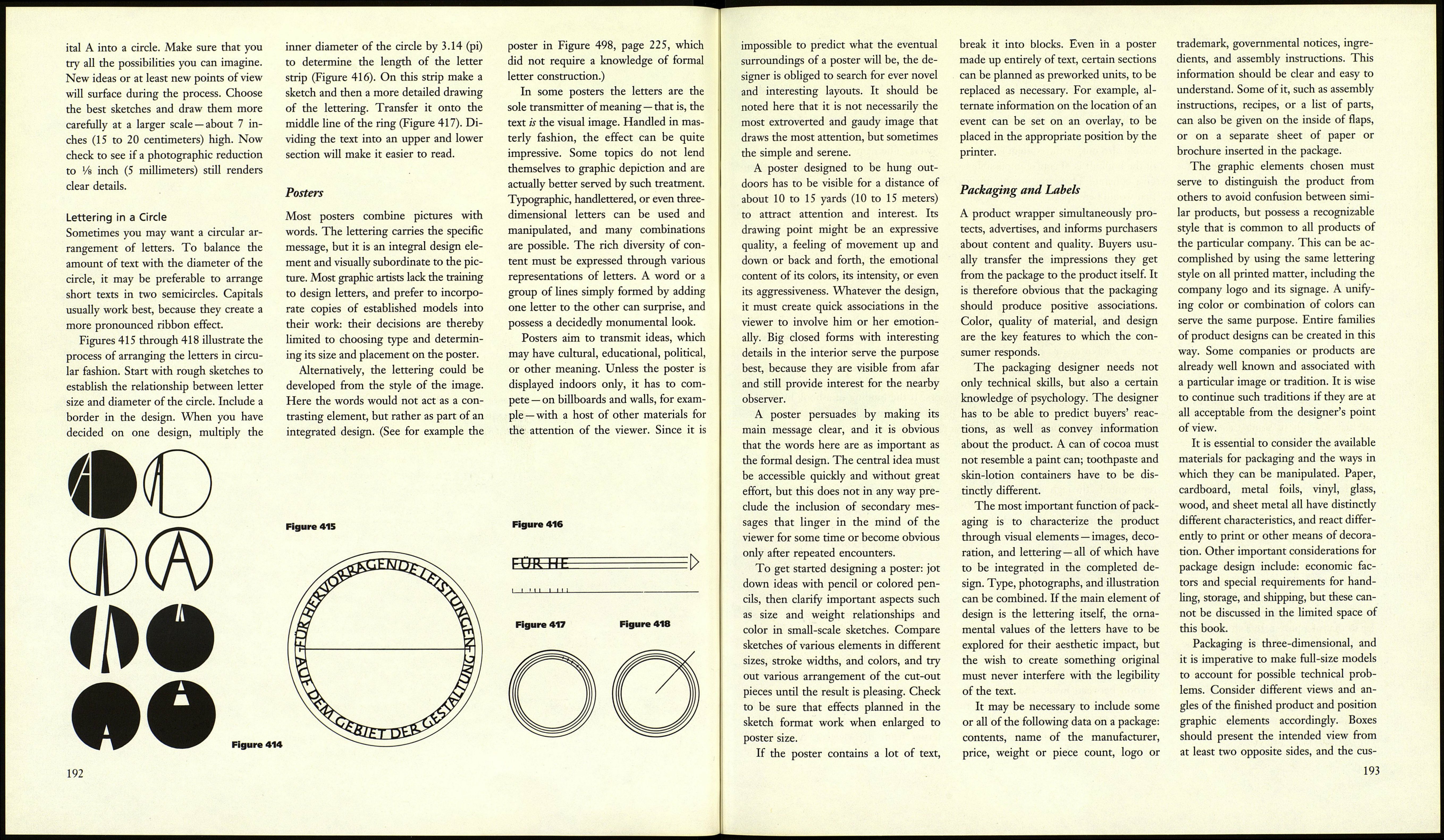

To get started designing a logo, make

a number of preliminary sketches. If one

of these looks promising, play with it in

a small format of about 2 inches (5 to 6

centimeters) in black and white. Figure

414 is an example. The topic for this

particular exercise was to inscribe a cap-

191