shown in Figures 473 and 474, page 221.

The earliest printed books were im¬

itations of handwritten ones. Today the

handlettered book should not seek to

emulate the printed book, but it is useful

to take into account the rich experiences

of typesetters, not just where the stricdy

technical aspects are concerned but

especially the considerations of logic and

aesthetics. For a handwritten book issues

such as format, decoration, letter size,

and arrangement of text blocks are less

constrained by the demands of produc¬

tion techniques than for a typeset book.

The designer has much more influence

on the final product and can express his

or her personality in many ways, freely

and unencumbered by many restrictions.

Different occasions — festive speeches,

works of poetry or prose, and so on-

demand specific forms appropriate to

their content. Legibility is an issue of

varying importance, as expressive poetry

may be better served by a lettering style

of comparable emotional value at the ex¬

pense of clear presentation of each letter.

Such variations and decisions are impos¬

sible to make in a typeset volume. Calli¬

graphy can be used to interpret and vis¬

ualize text in a way similar to illustration.

A series of planning steps is necessary

for the production of a handlettered

book, and these will be discussed in the

following sections.

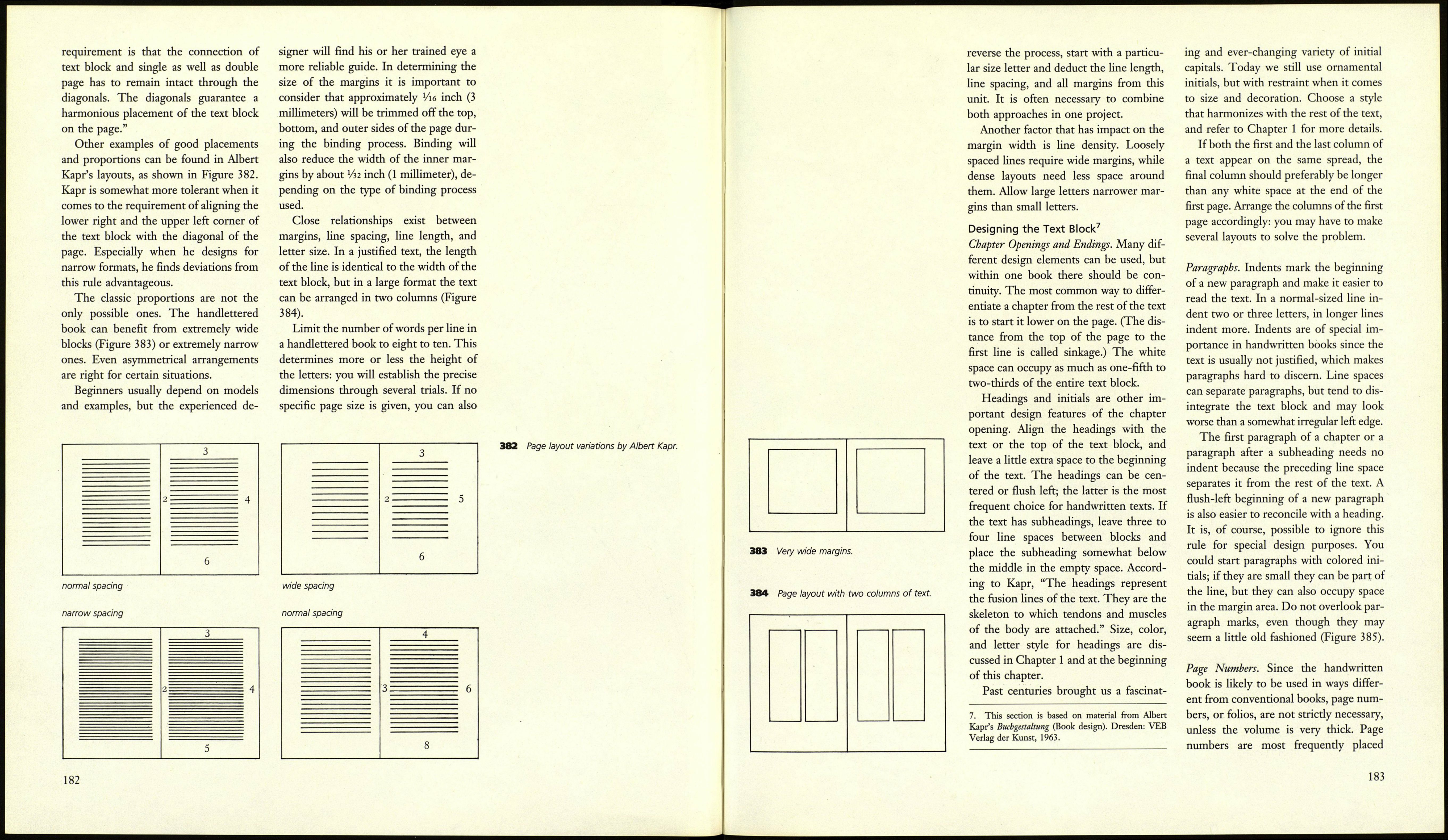

Format and Page Layout

If you are planning to use paper for your

book, you need to determine the grain

direction and the size of your sheet be¬

fore you decide on a format (see the sec¬

tion on Paper Structure, page 187).

There is an important difference be¬

tween layout for a single loose page and

for a book: the single sheet stands alone,

but a book opens to a spread — a pair of

facing pages that have to function as a

unit.

Every page layout has to be related to

the layout of the facing page. If the text

block were placed exacdy in the middle

of a page, surrounded by margins of

equal width, the spread would optically

fall apart in the middle. Jan Tschichold

wrote, "Harmony between page format

and page layout comes from equal pro¬

portions between both of them. If a

union is achieved between layout and

format, margin proportions become a

function of page format and the con¬

struction process. The elements are in¬

terdependent. The margins do not

dominate the page, they develop natur¬

ally from the page format according to a

form canon."6 Tschichold has recon¬

structed such a canon, which is the basis

of many documents and incunabula of

the late Middle Ages (Figure 375).

Tschichold found other ways to create

the same proportions. One is to divide

width and length of the page into nine

equal parts (Figure 376); another to ar¬

rive at the nine parts with the help of

Villard's Figure (Figure 377).

The nine-part division gives good re¬

sults even with other page formats.

Examples are 1:1.732 (the golden sec¬

tion—21:34), 1:1.414 (the international

A format), 3:4, 1:1, and 4:3 (Figure 379).

Tschichold considers the nine-part

system the most beautiful, but not the

only possible one. Referring to some of

the illustrations in his essay, which are

reproduced here, he further wrote, "A

twelve-part system creates a larger text

block, as we can see in Figure 16, ...

Figure 17 shows pages with the side pro¬

portions of 2:3 divided into six equal

parts. Along its length the paper may be

separated into any number of parts if

necessary. Margins even narrower than

those in Figure 16 are possible; the only

6. Jan Tschichold, "Papier und Druck" (Paper and

printing), in Typografie, Vol. 3, 1966.

I1

*------->

:

у

374 Раде formats, showing grain direction of

the paper: folio, quarto, octavo.

375 Jan Tschichold identified the plan of many

medieval handwritten texts and incunabula: the

proportions of the page as well as of the text

block are 2:3. The height of the text block

equals the width of the page. (Figure 5 of

Tschichold's essay, "Willkürfreie Massverhältnisse

der Buchseite und des Satzspiegels".)

\__s

\ y/

}\ _

У \ -

/ \

/ \

/ :: ::_s

/ \

376 Rosarvio's construction. Like Tschichold's,

it assumes page proportions of 2:3 but uses a

system of nine basic units. The result is the

same. (Tschichold, Figure 6.)

180

377 Villard's figure. The heavy lines make it 378 It is possible to use Villard's system to 380 Villard's system used to divide the page

possible to divide any other line into any number arrive at the nine-unit plan; page proportions into twelve parts. The proportions are still 2:3.

of segments. No rulers are necessary. remain 2:3. (Tschichold, Figure 8.) (Tschichold, Figure 16.)

(Tschichold, Figure 9.) jyg He¡gnt anc¡ w¡c¡tfi are divided into nine 381 Division of the page into six parts, with

parts. The proportions are 4:3. (Tschichold, the same proportions. (Tschichold, Figure 17.)

Figure 15.)

181