If the paper is not absolutely horizon¬

tal on the work surface, the gesso will

collect in the lower sections of the let¬

ters and the relief will be uneven in

height. Oudine the form with pen and

liquid gesso, fill in with a brush and

thicker gesso, and build the relief up

within the contours of the letter to a

height of at least Уз 2 inch (.25 to 1 mil¬

limeter) for letters of wide stroke widths.

The gesso will shrink as it dries, and it

is possible to add further layers, after the

surface has been slighdy scored with a

knife.

Work quickly. Delays may cause an

uneven surface, but small problems can

be corrected. Never burnish the surface

before the relief height is satisfactory: it

is difficult to add further layers to a

smooth one.

Gesso that has been accidentally

placed outside the letter can easily be cut

away after it dries; the same is true for

small drops of gesso spattered elsewhere

on the parchment.

Should the gesso become brittle dur¬

ing work, scratch it off and add glue or

binder to it, but frequent stirring will

prevent most problems. To predict the

length of the drying time is difficult: it

depends on the ingredients of the gesso,

the thickness of the relief, the humidity,

and the room temperature. Make some

samples of the same kind as your project

and test them periodically for dryness.

Thin lines have to be gilded before thick

areas. Johnston suggests drying times

from two to twenty-four hours.

Gold leaf has a tendency to stick even

to surfaces that are not covered with

gesso, so it is useful to cut a template

from lightweight paper to protect the

area surrounding the gesso buildup. Put

loose gold leaf on the gilder's cushion

and cut it with a gilder's knife; cut tissue-

backed (patent) gold leaf with scissors. Do

not sandwich gold leaf between two

178

sheets of paper. You can cut several

pieces at a time and position them at the

edge of a book or a box, as shown in Fig¬

ure 371, to use as needed.

To activate the stickiness of gesso you

have to breathe on it, section by section,

through a breathing tube (Figure 372).

Move the tube close to the surface, and

take care that your breath does not con¬

dense into drops that might fall onto the

gesso. Protect already gilded parts, as

well as those that have not yet been

treated, with strips of paper. The warmth

will dull the gold, while gesso that gets

warmed up too early loses its ability to

hold the gold leaf.

Apply the gold immediately after the

gesso is warmed. If you use a gilder's

knife to cut the gold leaf, you will also

need a gilder's tip — a brush used to pick

up the cut sections. Touch the tip to the

gold and it will adhere easily. Now hold

the tip over the spot that is to be gilded

and, using a cotton ball, press the gold

onto the paste from the back side of the

frame. This procedure is not only con¬

venient but also safe.

If you cut the gold leaf on tissue back¬

ing, set the gold onto the warmed gesso

and, with your fingers, push it down

gendy paper side up (Figure 372). Then

remove the tissue backing. Cover the gold

with glassine. Hold it in place with your

left hand so that it will not shift during

the following procedure and push the

gold onto the gesso through the glassine

with the pointed end of the burnisher.

Then rub the entire surface with the flat

side of the burnisher. If you are not sure

whether the gesso is hard enough for this

procedure, use a tighdy rolled wad of

cotton instead of the burnisher.

If the gesso dries out before the gold

is applied, it will not adhere well. The

same thing will happen if you touch the

prepared gesso and leave a trace of oil.

To remedy this problem, roughen the

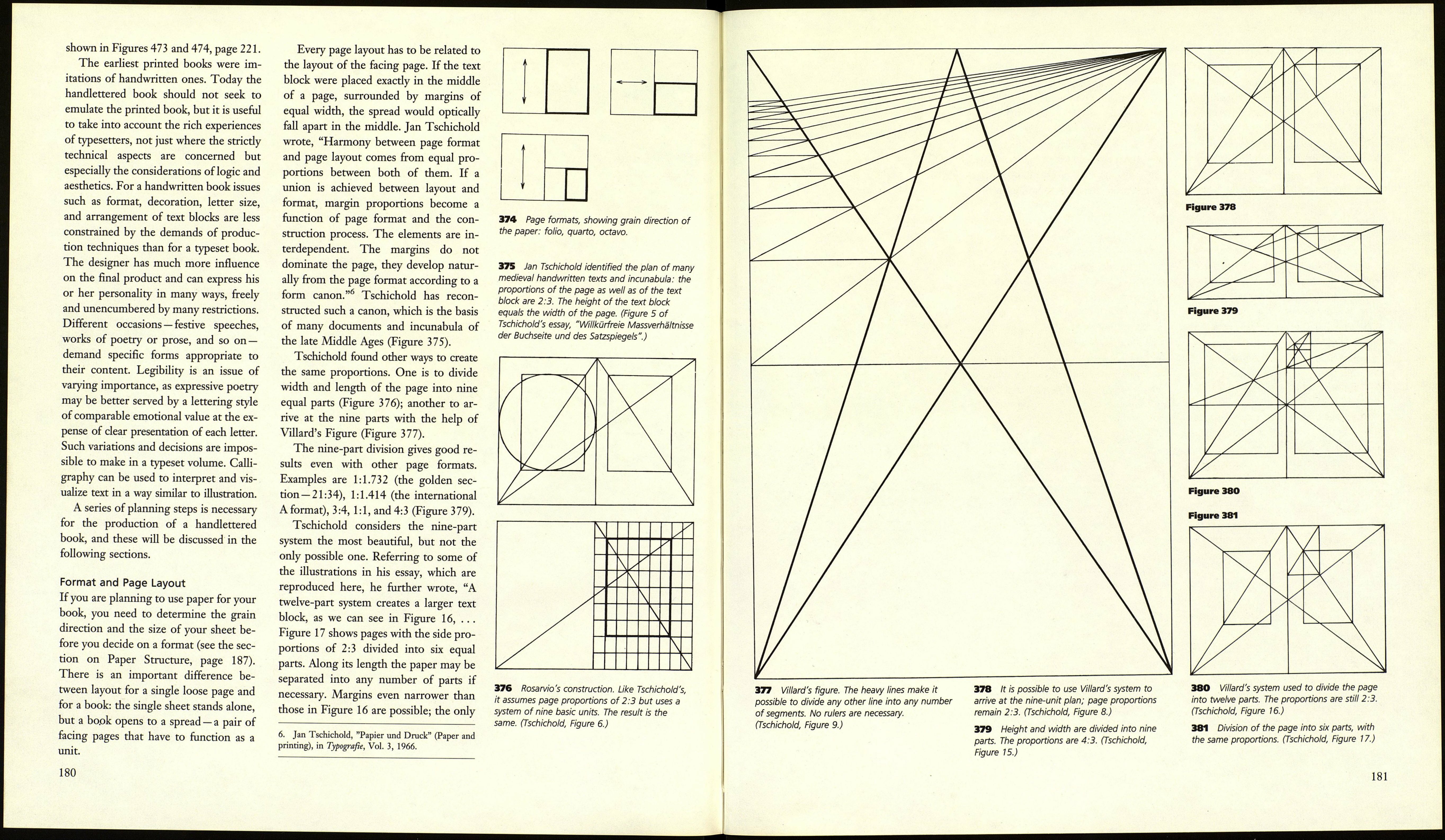

373 Page (reduced) from a handlettered book

of Paul Eluard's poetry, I am not alone, by

Irmgard Horlbeck-Kappler. Leipzig, 1963.

surface and apply a fresh layer of gesso

or a thin layer of glair, which can also be

used as adhesive for small repairs in the

gold leaf.

Keep adding layers of gold leaf until

they no longer adhere. You may need as

many as three or four layers, because

gesso particles can penetrate the first

layer, especially if it is too liquid or if the

gold leaf is very thin.

Do not burnish until you are certain

that the gesso has dried thoroughly, and

test a sample piece. Homemade mixtures

are ready for burnishing just a few hours

after the gold application.

Start the burnishing process with

round movements of the burnisher, and

continue with straight strokes. If you

feel any resistance at all, stop im¬

mediately, look for any gesso on the bur¬

nisher, and remove it. This problem can

be caused by too much glue in the mix¬

ture or by insufficient drying time.

Sometimes it is enough to add more

gold leaf and wait a little while before

burnishing, but if the second attempt is

not successful either, you have no choice

but to scratch off the gesso and start

anew.

Small imperfections in the layers or in

the burnishing become clearly visible if

you use a strip of white paper as a reflec¬

tor. Protect your work from the humid¬

ity in your breath, and never touch it

with your fingers.

Excess gold leaf is usually easy to re¬

move after burnishing is completed. If

you cannot clean the pieces away with a

brush, scrape them off gendy with a

knife. Burnish again after eight to ten

days, and once more two weeks later.

The Handlettered Book

General Remarks

Since the advent of printing, its ever-

increasing popularity has displaced the

handlettered book as a means of mass

communication, education, and enter¬

tainment. Today, the raison d'etre of the

handlettered book lies in the realm of

bibliophilia. Each piece is produced in¬

dividually, though it is possible to repro¬

duce a given work in small editions by

way of lithography or offset printing.

For more or less official occasions,

speeches, company histories, and the

like can be presented as handlettered

volumes and make appropriate gifts to

honored guests as souvenirs of the occa¬

sion. A well-executed calligraphic design

can meet such requirements more effi-

ciendy than a typeset book, since the

small number of copies needed would

rarely justify the necessary time and ex¬

pense for commercial typesetting and

printing.

The importance of the handlettered

book for private use should also not be

underestimated. There can hardly be a

more personal or unique gift. For many

of these works it would be difficult to

find a publisher, but it is possible to

create a small library of handwritten

books for specific purposes. For exam¬

ple, Goethe's father collected his son's

early poems in this form.

A third group of handlettered books

consists of artists' books — works created

by painters or graphic artists who are

less interested in the official or private

motive for the text, but rather wish to

interpret the contents in their own way.

This can be done using lettering alone,

but more often the text is combined with

illustrations, and the best results come

from works in which the character of all

elements is carefully matched — for exam¬

ple, the works of Matisse and Picasso

179