Nineteenth-Century Display Styles

One of the side effects of the industrial

revolution in England was the advertis¬

ing industry. Advertisements, posters,

and other printed matter created a de¬

mand for eye-catching and effective

typefaces, some of them larger than ever

before. European firms were quick to

adopt and further develop the new Eng¬

lish typefaces. First came the bold

roman of neoclassical style, followed by

Egyptian, Italian, and Tuscan faces in

many variations. Their names allow in¬

ferences to the original purpose. Egyp¬

tian, one assumes, was created to satisfy

the interest in all things Egyptian that

arose in England after Napoleon's ill-

fated campaign, Kapr says. Type pro¬

duction became the domain of industry.

Foundries were engaged in competition

with each other, which was beneficial in

the beginning, but catastrophic in terms

of artistic quality soon afterwards.

Catalogs hawked well-designed and ques¬

tionable alphabets side by side; type

design degenerated into mere technique.

Display typefaces are of great impor¬

tance again today. The following sec¬

tion presents an overview of the most

useful display types. Basic forms can

easily be varied and adapted to specific

applications.

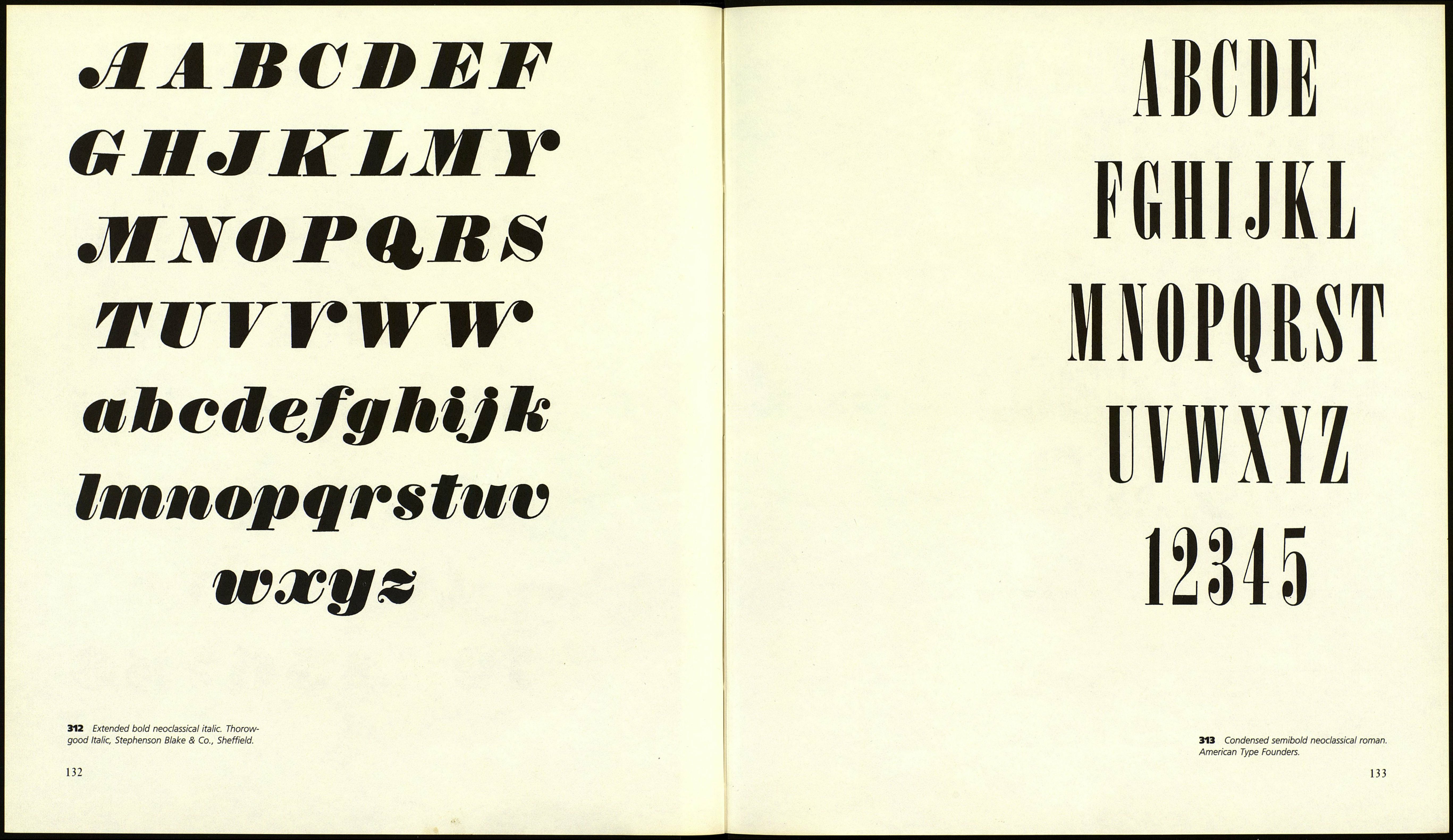

Bold Roman Neoclassical

An extreme contrast between thick and

thin distinguishes bold roman neoclas¬

sical types, also called fat faces, from

the neoclassical roman. It can be quite

elegant, nevertheless. Keep the interior

spaces narrower than the stroke width.

Variations are shown in Figures 314

through 325.

Egyptian and Italienne

The first of these types were probably

created before 1806 in the foundry of

Robert Thorne (according to Muzika).

The thick/thin contrast is reduced to a

minimum. The stress of the round forms

is vertical, the capitals are matched to

each other in width. The serifs are rect¬

angular in shape (slab serifs) and the

same width as the crossbars. Earlier ver¬

sions have straight serifs, later ones are

bracketed. A common name for these

was Clarendon, after the type of that

name. Both basic forms in various

weights and excellent new copies have

been produced during the last few years

by several foundries: Volta by Bauer,

Neutra by Typoart, Clarendon by Haas,

Egizio by Nebiolo, as well as some faces

for typewriters. The illustrations show

that Egyptian is a good starting point for

a variety of decorative variations. Only

some later Italienne types are worth

mentioning. They differ from Egyptian

in the horizontals, which are bolder than

the verticals.

Tuscan

In 1815 Tuscan type was introduced in

England by Vincent Figgins. Its pecu¬

liarity is bifurcated stems and serifs, a

device already popular during antiquity,

the Renaissance, and the baroque era.

Tuscan faces can be developed from

Egyptian or from Italienne.

Sans Serif

There are different opinions about the

first cut of sans serif, or grotesque, type.

Albert Kapr quotes the year 1803 in

his Klassifizierung der Satzschriften' and

the company as Thorne, while Frantisek

Muzika credits the Caslon foundry in

the year 1834 as the creator of the first

sans serif alphabets, which were cut as

4. Albert Kapr, "Die Klassifikation der

Druckschriften" (The classification of printing

types), in Schriftmusterkartei. Leipzig: VEB

Fachbuchverlag, 1967.

"Egyptian without serifs" (Muzika).

(The first known example of a sans serif

was from William Caslon IVs 1816

specimen book.) The horizontals are

only slightly narrower than the verticals,

the stress is vertical, the width of the

capitals is almost equal. Many variations

are possible through changes in stroke

width and letter width. The condensed

medium sans serif is the most useful

of them.

Historic sans serif typefaces are

graced with a certain liveliness and

charm, and it should not surprise us that

type designers try to approach the his¬

torical wellspring of type yet again with

creations such as Folio, Helvetica, and

Univers, after they exploited all the pos¬

sibilities of constructivism during the

twenties and thirties. Univers is of spe¬

cial interest, because it contains vertical

and diagonal bars that are differentiated

in accordance with the principle of

changing stroke width in the roman,

a characteristic that has influenced the

way we all see type. The width of the

capitals is less uniform than in other sans

serif styles.

130

ABCDEFG

ІІІ.ІІІЬтІЛ

OPQRSTU

VWXYZ

abcdefghij

klmnopqrs

tuvwxyz

311 Extended bold neoclassical roman.

Thorowgood, Stephenson Blake & Co.

.