RENAISSANCE ROMAN AND ITALIC

Renaissance Roman

As part of the pervasive reorientation

that took place during the fifteenth

century in Italy in practically all areas of

learning and culture, the art of lettering

was also affected. The Italian humanists

found much of the ancient literature

written in Carolingian minuscule and

adopted this as book type (to paraphrase

Muzika, lettere antiche nuove). The type

was purged of all archaic remnants, the

sequence of moves became conscious,

letters like a, g, and r assumed a new

shape. Capitals from the Roman monu¬

mental capitals were added, the stems of

the minuscules were fitted with serif-like

strokes. The Gothic tradition was over¬

thrown in several stages. Arabic nu¬

merals first appeared in the fifteenth

century.

During the sixteenth century the

printed word supplanted the handwrit¬

ten one in the production of books. Ever

since, the history of letters is the history

of printing type, which continues to draw

inspiration from handlettering. Until the

end of the nineteenth century, however,

type forms moved ever further from

their origins at the time of Gutenberg.

The first Venetian types show a

strong effort to copy handlettering as

closely as possible, for example, the

Jenson roman of 1470. Characteristic of

early Venetian forms are the slanted eye

of the letter e, still evident in Centaur, a

modern version of the Jenson. But the

engraver of Aldus Manutius's type for

De Aetna (1495) and Hypnerotomachia

Poliphili (1499) started using his tools

not only to re-create but to create. Bold

type became pronounced, serifs more

differentiated. Capitals were modeled

after classical roman types.

The Hypnerotomachia served as model

for the French Renaissance roman. The

type created by and after Garamond

(1544) soon could be found all over

Europe.

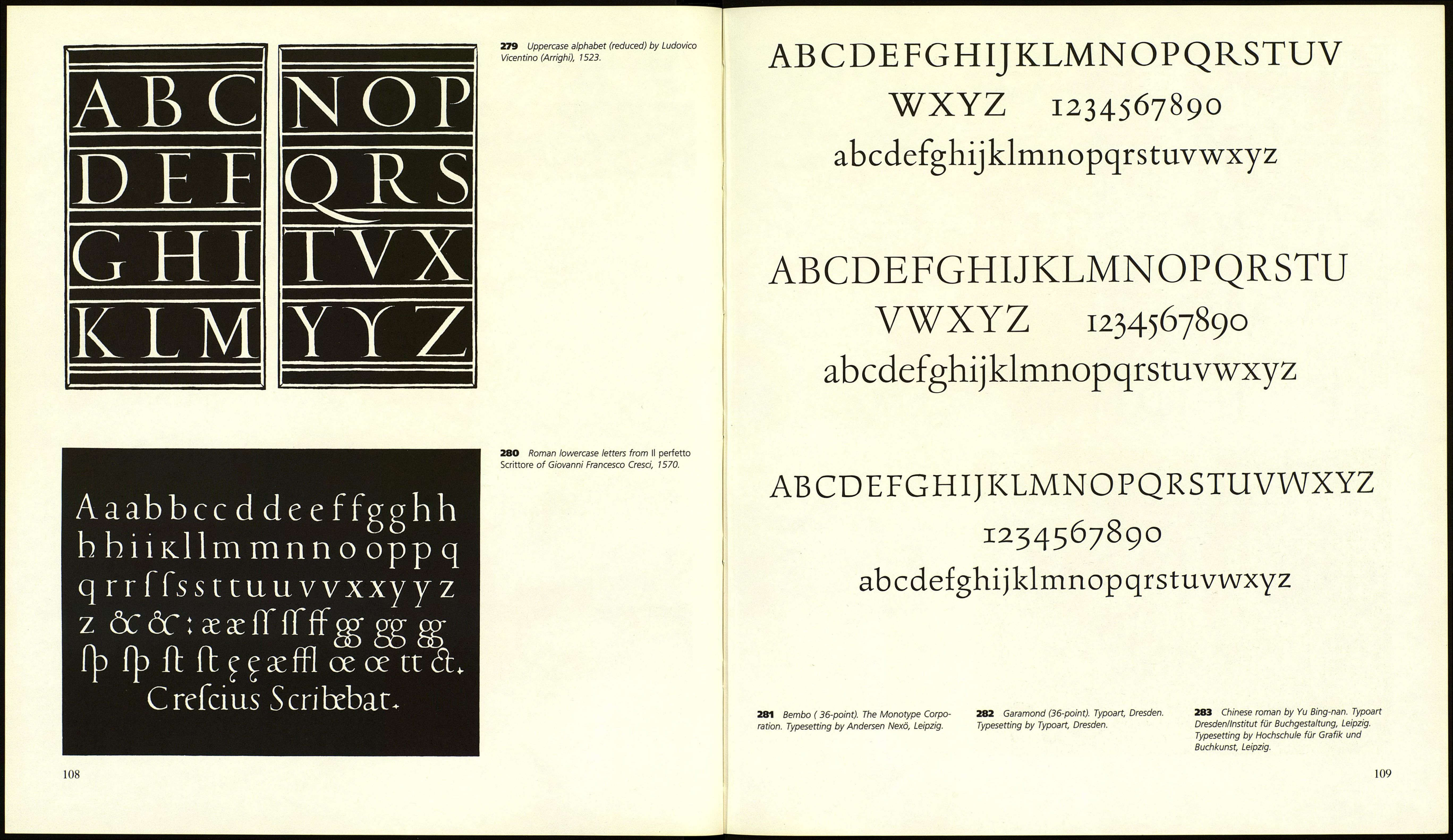

In use today are replicas of the Renais¬

sance roman types by Aldus Manutius,

Bembo and Poliphilus. French types in¬

clude replicas of Garamond and Jannon.

Other modern creations using French

and Venetian inspirations are Weiss

Roman, Palatino, Trump Mediaeval, and,

in Germany, Tschörtner.

collezreraiîcum лхлаЪтхяіW a, nume merer ckcemutr. Cum cm mot

iutf tifa. Serrer uxAtrer ааесааЛ! utrum риийтт earn aux ліяоСсопйІлгѵ

{alonar лсаіСлйхтс fer LuterafудшстчЬцГ utrtnf q tm* confami Ao fatine.

Ітлл uiAsxxú. txuî тллті опАгтапГгсЦ: uerttufme-tpie coiitm,^at ca.ouc'

шАшжт /Lea ца»гі 'лесаеея «»« - Фглиюгл^Лііжі^тл. at/uSbc/nxxatt jfirt>ra -Ac

TruJnttimbruef otftao ibtumerar-ur nature",tibi, nue-populo cKfceneut

dtotur fmueruium cfrv Ham cum tntr-mm foLumcpceratuf-uu/feri orruu

ашлѵ ас peneqmcuxcxnutcb, ocuti {vre trunúnc attor -propter auenv fora

opef ceceri {limai cum ipium orraimo detnLttxniuuien, • Qvu&möbrem

Accepiíh tu qiuacm dolorem iá cnTimiuíb. cm.finule' wttrrif nibtliu-

Figure 275

Figure 276

prouécum Ifrael etiam appellams eft duobus noíbus ,ppter duplicem

uirtutis ufú.Iacob eim athlerá & exercétem fe latine dicere pofìumus:

quamappellarioné primú habuit:quu praAicis operanoíbus multos

pro pietate labores ferebat.Quum autéíam uictor luchando euafit:<3¿

fpecularionis fruebatbonis:tiic Ifraelem ípfe deus appellarne ггегпа

premia beatitudméqj ulcimam qux in uifione dei confiftit ei largiens:

hominem enim qui deum uideac Ifrael nomen figmficat. Ab hoc.xiï.

106

275 Humanist minuscule (historie form). From

Arndt/Tangl, Schrifttalfeln zur Erlung der lateinis¬

chen Paläographie, Berlin, 1904.

276 Roman of Nicolas Jenson, Venice, 1470.

From D.B. Updike, Printing Types, 3rd edition.

London, 1962.

Z77 Ductus of crossbars and serifs.

278 Renaissance roman. Study by the author.

Figure 277

**

i-*

it

ABDEGHJKLMNOPRSTUVWXYZ

abedefghijklmnop qrs tuvwxy

Über die Nachahmung. Der nur Nach¬

ahmende, der nichts zu sagen hat zu

dem, was er da nachahmt gleicht einem

armen Schimpansen der das Rauchen

seines Bándigers nachahmt und dabei

nicht raucht. Niemals nämlich wird die

gedankenlose Nachahmung eine wirk-

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzß

ABCDEGHl]KLMNOPRSTUVWXyZ

Figure 278

107