which served as the model for the

type used in Gutenberg's Bible.

which served as the model for the On page 91 :

.____________1 ;_ /^__.___i______j_ t>íi_i_

GOTHIC LETTERS AND

THE RENAISSANCE

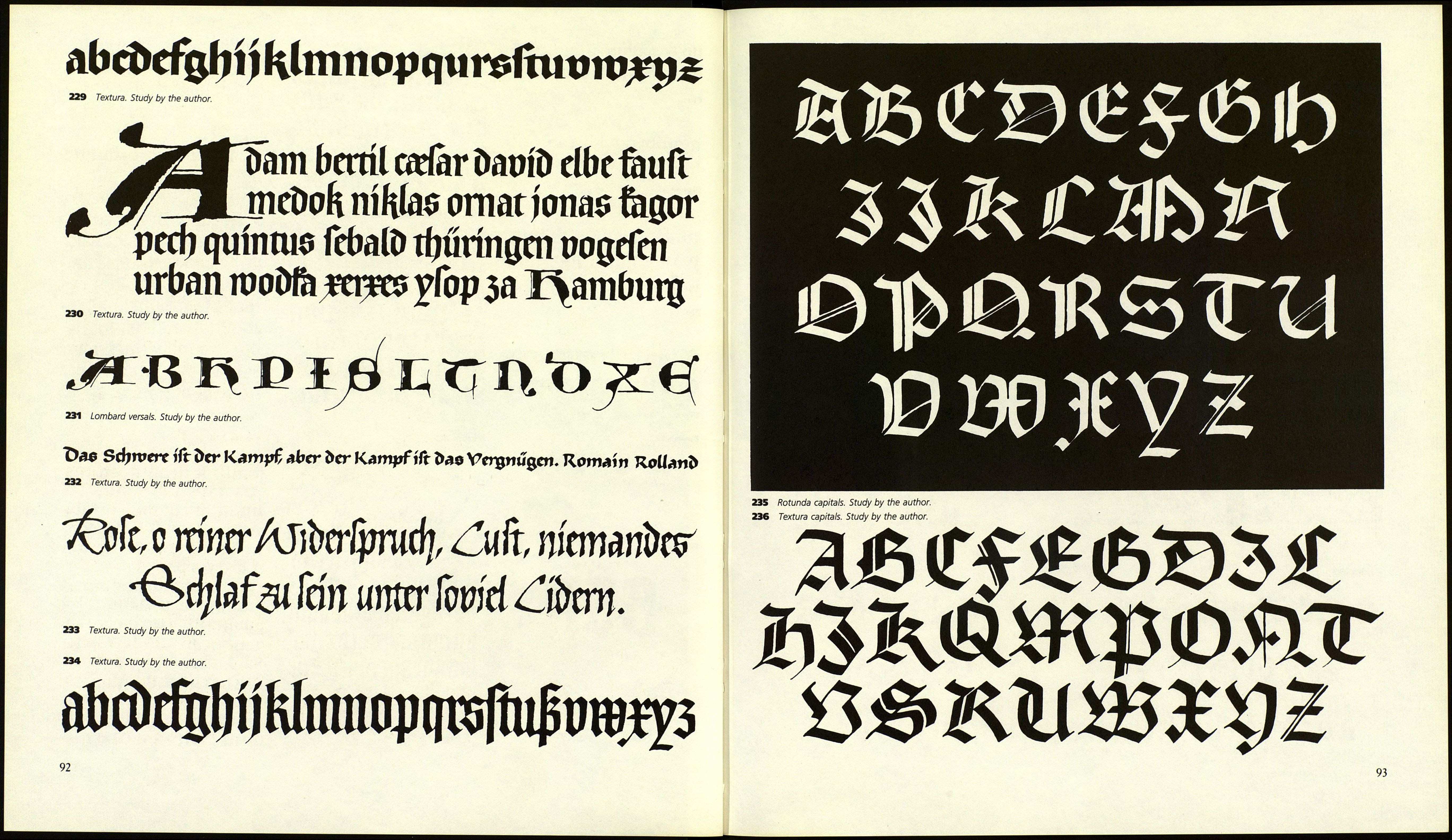

Textura

Under the influence of the Gothic style

in the twelfth century the x-height forms

of the Carolingian minuscule grew nar¬

rower and taller. The arches, entries,

and exits of letters started showing a ten¬

dency to "fracture." From these early

Gothic bookhands all later textura, or

blackletter, styles were generated, by re¬

placing all rounded forms with broken

lines. The form canon was established in

northern French monasteries at the end

of the twelfth century and was gradually

accepted by all other western European

monasteries. In the German realm tex¬

tura found an important expression in

missals.

Textura letterforms are narrow and

written with a broad flat-edged nib for a

strong contrast between thick and thin.

Verticals are connected to each other

with rhomboid forms, and these interior

spaces are frequently narrower than the

stroke width. Distances between lines

and words are very small. The letter a

consists of two parts, and a broken un¬

cial form serves as d. The f and the long

version of s reach only to the baseline.

Legibility is hindered by the dense let¬

tering, by relatively few ascenders and

descenders, and by the multitude of

ligatures.

Referring to different stem shapes, the

following groups can be distinguished:

1. Textura with rounded ends (four¬

teenth century)

2. Textura with broken ends (four¬

teenth century)

3. Textura with straight ends (four¬

teenth to fifteenth centuries)

4. Textura with rhomboid-shaped

ends. This is a late development,

The third form of blackletter appears

in French manuscripts. A skillful twist of

the pen in the lower part of the stem

creates horizontal ends. Since fractured

forms appear only at the upper but not

at the lower ends of letters, a very attrac¬

tive contrast results.

A fourth variation is the execution of

textura in stone, bronze, or wood. Here

the letters are not engraved but raised.

Some inscriptions were painted or cut

into wood for printing purposes. The

latter technique furthered ever pointier

entrance and exit strokes, an effect that

was later mimicked in some typefaces.

For special occasions, forms of roman

capitals and uncials as well as rustic cap¬

itals with elements of Gothic script were

used. An original and very ornamental

set of capital letters was developed from

Gothic elements and the addition of

minuscule forms. These so called Lom¬

bard versais were drawn with a brush in

attractive contrast to the common style.

Rotunda

Textura could not hold its own for long

in Italy and Spain. At the end of the

fourteenth century it was fused with

Latin traditions into rotunda. Like tex¬

tura, rotunda is characterized by thick

vertical strokes and short ascenders and

descenders, but it appears wider, roun¬

der, and lighter in spite of many liga¬

tures and the frequent contraction of

letters. Intermediate forms came from

encounters with humanist minuscules.

Many typefaces were created in the

image of rotunda and a later form of it,

the Gothic. They were very legible and

popular even outside of Italy. Only one

form of it is still in use, in German-

speaking countries — Koch's Wallau.

219 Early Gothic bookhand (historic form).

From Hermann Degering, Die Schrift (Lettering).

Berlin, 1929.

220 Textura (historic form). From Hermann

Degering, Die Schrift.

221 Textura (historic form).

222 Textura. The bars have horizontal ends at

the baseline (historic form). From Albert Kapr,

Deutsche Schriftkunst (The art of German letter¬

ing). Dresden, 1955.

223 Textura (historic form).

224 Type from the forty-two line Gutenberg

Bible. Mainz, 1455.

225 Stroke endings.

226 Ductus.

227 Woodcut for the title page of Hartmann

Schedel's Chronik. Nuremberg: A. Koberger,

1493. From Hermann Degering, Die Schrift.

228 Italian rotunda, fourteenth century. From

Ernst Crous/Joachim Kirchner, Die gotischen

SchriftartenfThe art of Gothic lettering). Leipzig,

1928.

218 Medieval initial. From Graphik, repro¬

duced by kind permission of Karl Thiemig KG,

Munich.

90

utf9AtmnitCAÍu|iiiqum

Figure 219

Figure 220

ttrnip2(flifflgQuimmcJ

p#uttnfiapimutëituu

teto -JUmaítet jjtaii£

Figure 221

qtlumammtratratt

qtic:uf(padanima

Figure 222

Figure 225

1 2 3-4

Figure 226

mmtmûttfiïm&ai

mutmmtttë ofimv

tlüWOVflßttttffiWt

Figure 223

Figure 227

utófltt ваиШ:йстйй in

^іШдп antan omimtea

;tmuailtraptfaïm.Jftt5*

tû опт tórma Ai afrenta

ìm-ttfiimbia mat mann

ját una au ШшШ. jMmtòe:

ìmbo pijíüffijm in mann

ecgoiianmaöfaaalpifara^

[flit ma ibi n tóftt jbiuffit

ma mma rota ratrfitut ЬЬ

imjßroptma norato I no*

t?baalpljararnn.iftrditj[*

iptilia fnarq tulit îaui 0 tt

tfftiîmmt au if иг pfyiltffi*

öccmtrn: mffuHi Cut t таІІ£

Rjfnlnit autf oaniu опт.

i rotea piñlí&oa:* traûaf

Figure 224

Figure 228

fhaiur Ce in tramutino*

ftum \vtkt cU mati6.Z*>

rmut firn споішб/ф Tubi

intra:' roenitr Ьх рссссг

ѵю ïum engnus. TlumqjD

n qf om* pant* ma^u

i imo ісш coiti tcmòltrac

Ьшіш oc panane до bri

pubUcmú i pecare. Tît

)iilo uuxö. 4tatupipc il

05 cnçcnô (c uirotbfu* i

плѵшпшб ttncubuô.ma^

Ȕfafptnjs. cr (fplics pat

iium Ditfit. Tu ce crus»