abbcdefghij

klmnopqr

stuvwxyz

1Ï1 / nwprrase letters nf a sans serif even- ■'

121 Lowercase letters of a sans serif even

stroke roman.

ä b cl eg h

122 Ductus, or stroke sequence and directions.

aaabbddptfjk

mnnuusseee

123 Poor letterforms.

Figure 124

Figure 125

Hnbg nd

Lowercase Letters

Minuscules were developed from majus¬

cules over a long period of time. Several

form changes took place which can only

be appreciated when the historic context

becomes clear. We are turning our at¬

tention to lowercase letters at this point

because they make up the vast body of

printed and written material in our time.

Long texts made up entirely of capital

letters are difficult to read.

Figure 124 shows the proportions of

stroke width to height: the x-height is

about six and a half times the stroke

width. Capitals of the same type should

have a height of nine stroke widths. The

ascenders are somewhat taller than the

capital letters, which would otherwise

appear too big and cause optical holes in

the page design. Mark the waisdine, which

defines the upper end of the x-height,

with a pencil line. Ascender, descender,

and cap heights are best estimated.

Lowercase letters are grouped differ¬

ently from capitals. Practice m, n, h, i, u,

and о first, and tune their widths to each

other. Write your m with smaller in¬

terior spaces than n. Do not represent о

with a circle, and practice related forms

along with it: b, d, e, g, p, and q. Keep

writing m, n, h, and u, and add the

newer letters to your repertoire. The

letters k, v, w, x, y, z, s, c, and l should

not pose any new challenges, since they

correspond closely to the capital forms.

The last group consists of a, t, and j.

Make the t with a flat bottom arch; treat

j in a similar way, and place the crossbar

of the t somewhat below your auxili¬

ary pencil line. Common mistakes are

shown in figure 123. With some practice

the lowercase even-stroke roman letters

can be made easily with a flat brush.

Special attention is required at the spots

where arched forms meet straight lines.

Avoid blobs of ink at these points by

thinning the lines before they meet. To

52

1Г if

right

nib edge too flat

nib edge too steep

ffttt

Figure 127

right

wrong wrong

right

wrong

ritjuic ЛЛЛ»

ІГ/AVOS

Figure 129

ГГЛІЛЛ

right

wrong

right

wrong

MM

wrong

right

NÑ

wrong

right

wrong

achieve this effect, simply lift the brush

off the paper slightly (Figure 125).

Sans Serif Roman with

Figure 126 Different Stroke Widths

Uppercase Letters

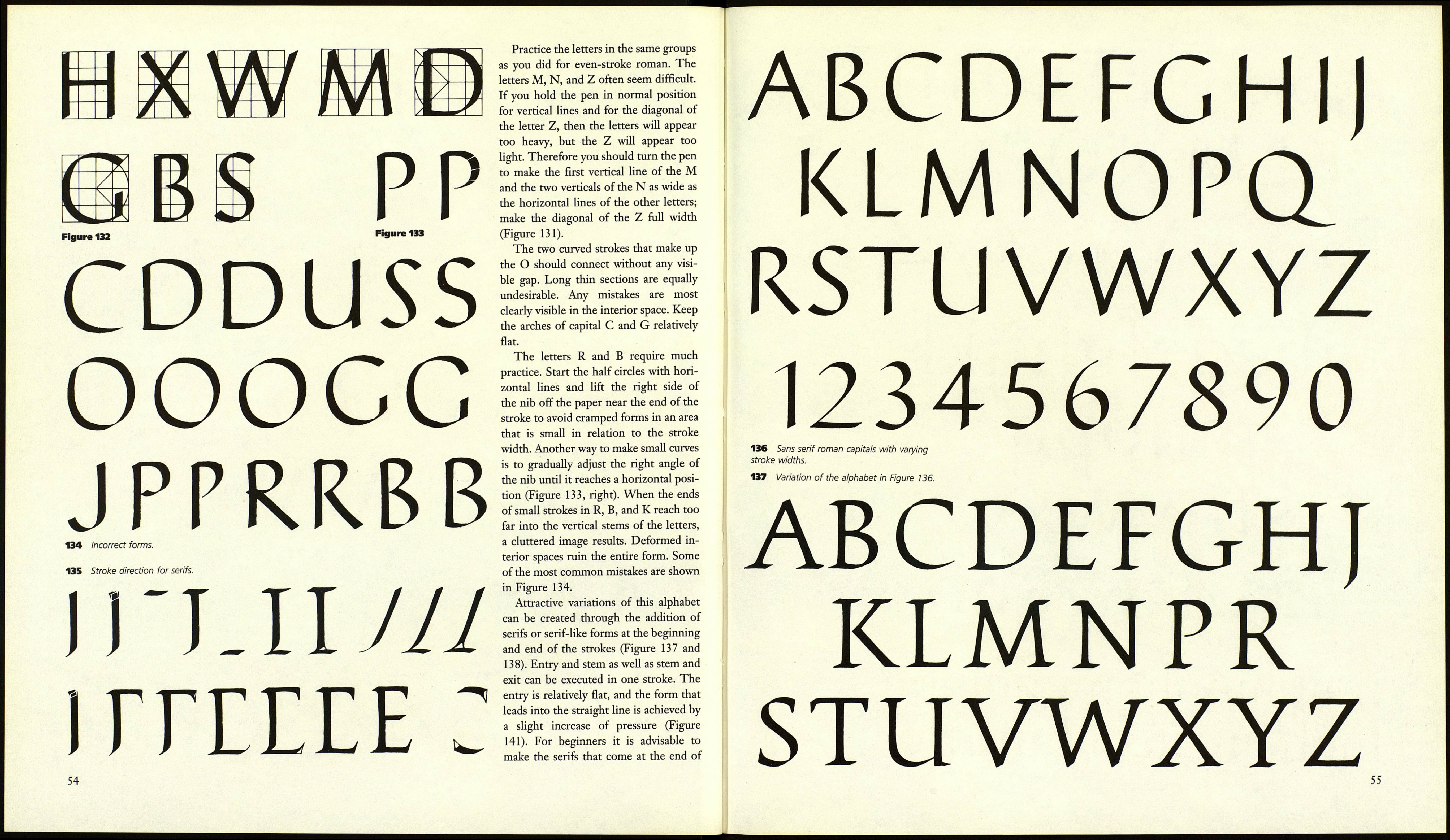

Capitals made with different stroke

widths are subject to the same consider¬

ations of proportion as the even-stroke

letters. The angle of the pen is of utmost

importance, however: it determines the

character of the letter (Figure 12 6).

After you have decided on the stroke

width and letter height, proceed in the

same manner as for the sans serif (Figure

127), and practice the basic strokes (Fig¬

ure 129). Try to give each stroke a defi¬

nite beginning and end. Touch the pen

nib to the paper with some pressure and

lift it slightly to form the stroke, but

make sure that it always remains in con¬

tact with the paper. Increase the pres¬

sure slightly again just before you lift the

pen off the paper (Figure 128). All hori¬

zontal lines are formed in this way. Too

much pressure will result in black spots

at the end of the stroke and should, of

course, be avoided. Corners look better

if the horizontal lines slighdy overlap

the verticals to which they are attached

(Figure 130). Where two diagonals

meet, the wider stroke can also overlap

Figure 130 the other one.

For round shapes hold your pen as

you would for a horizontal stroke, but

make the widest part of the stroke in the

middle of the movement and end the

stroke in a point. A diagonal axis will

Figure 131a result.

Practice separate shapes by combin¬

ing them in rows of ornaments, and add

further interest to the exercise by using

red or blue ink for some rows. For a be¬

ginner, this new challenge of using and

distributing different hues is of great

Figure 131b value.

wrong

53