ѲбВІНіН fH

Figure 112

Figure 113

F FF

E ЕБЕ

Z ZZ

N N

К KK

V VW

X XX

Y Y

M MM

WWW

С CC

G GG

GC

D DD

BIBBB

A AAA 0 00

AA O0

RKRK

sLsss

U UU

P PPP

] IJ

Figure 114

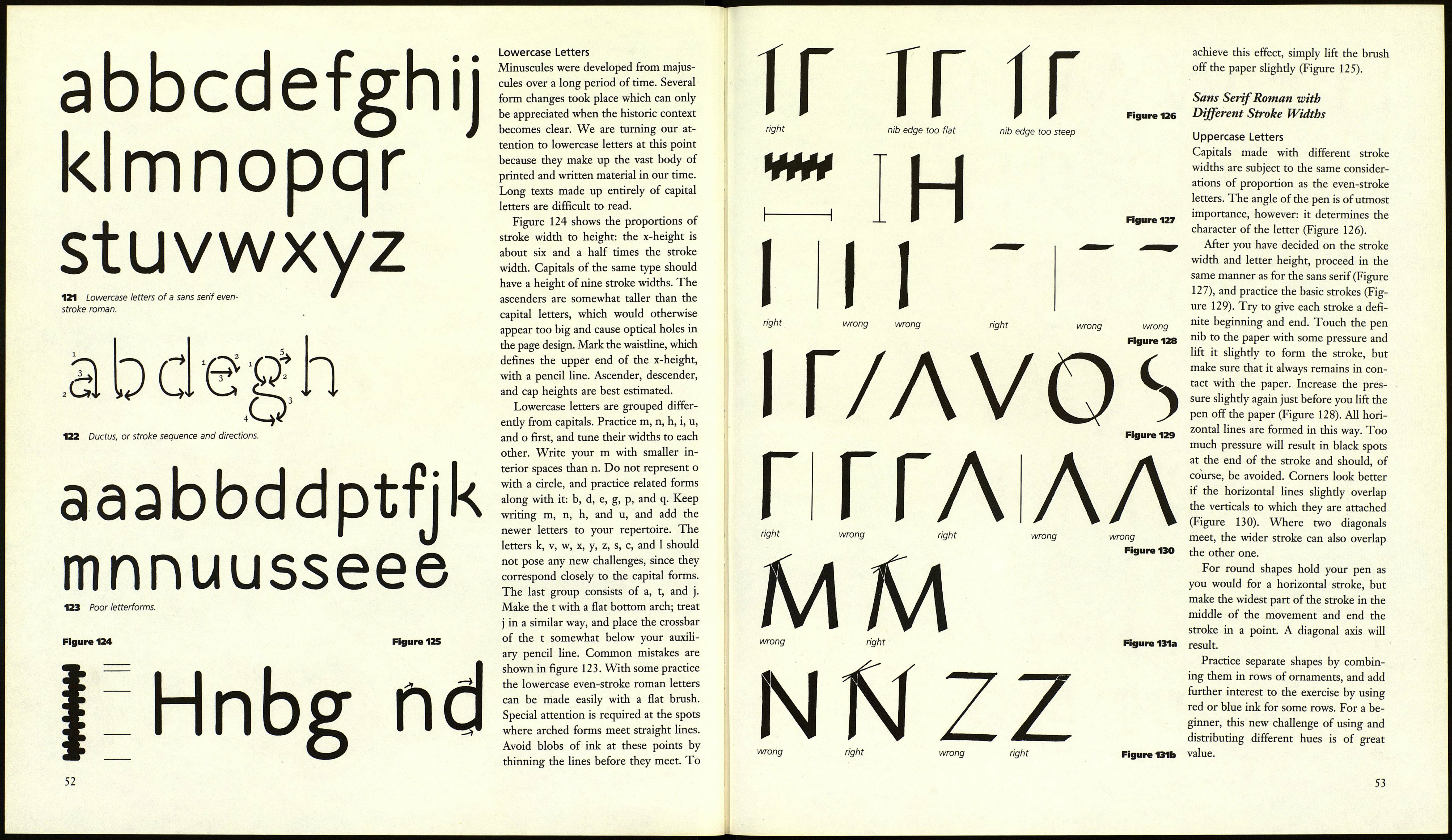

poorly proportioned interior spaces. Fig¬

ure 114 shows some of the most common

mistakes.

Check the way you hold your pen. If

you make errors in writing, do not try to

correct them; let them stand and mea¬

sure your improvement against them.

Some letters are so difficult to write that

you will need considerably more time to

master them than others, but resist the

temptation to fill lines and pages with an

endless repetition of the same form. Do

not add alphabet to alphabet in series

or in vertical alignment of the same let¬

ters. Write words, and pay attention to

groupings of letters and the spaces

50

between them (see Spacing, page 23).

When you are comfortable with one

group, proceed to the next, then mix the

letters; rearrange them into other words

and later into running text. Finally,

practice the letters in various stroke

widths (1:8,1:7,1:6). Only the light and

medium weights will look good; if the

strokes are too bold for the size, you

have no leeway to counteract optical

illusions.

Lettering with a Brush and Other Tools. If

you practice lettering not merely as a

hobby but with more serious intentions,

you should become familiar with the use

of a brush. Letter on wrapping paper, on

paper samples, or on any other cheap

material. Rough surfaces resist the pull

of the brush and create interesting ef¬

fects. Letter on a variety of papers and

on surfaces that are primed with paint.

As before, it is best to work on a slanted

table: the working surface should be

propped up at an angle of at least 30

degrees.

Strokes up to lA inch (6 millimeters)

wide can be made without the aid of a

mahlstick. The section on Brushes, page

36, describes the right way to handle a

brush. It is very important that you wipe

the brush on all sides after you dip it. Do

•

not push down while you write, and keep

the ends of all crossbars nice and round

and of equal thickness. The rounded

ends can be corrected with a flat brush

if absolutely necessary.

Stroke widths of more than 3Л inch

(2 centimeters) can be executed with a

pointed brush, but the result is often

aesthetically disappointing. For large

letters, flat brushes usually yield better

results.

Liner or script brushes with their

longer hair belly can be used for large

letters, but their use requires a great deal

of practice, since it is easy to twist them

out of shape at round sections of the

letters. Use bristle brushes for letters

Figure 115

that approach 3Л inch (2 centimeters) in

width. Grip the tool near the ferrule and

guide it with a movement from your

shoulder and your elbow. Neither your

lower arm nor your wrist should rest on

the paper: only your pinky can be braced

against the surface. Use a mahlstick for

making straight lines, if you wish (Fig¬

ures 90-92). Hold the edge of the brush

horizontally for vertical lines and verti¬

cally for horizontal lines; for cursives,

turn the brush (Figure 115).

Practice using a flat brush to make a

condensed sans serif (see Condensed

Sans Serif, page 39). Here interior

spaces are small and technical difficulties

manageable.

Even-stroke roman letters acquire a

new and interesting aspect when they

are made with different instruments.

Figure 116 shows letters made with a

watercolor brush; the letters in Figure

117 were drawn with a felt-tip marker,

and those in Figure 118 with a wooden

stick. Letters cut in wood have a distinct

character (see Figure 423, on page 205).

Yet another effect is achieved with posi¬

tive images cut in linoleum, attached to

wood blocks, and used as stamps. And

letters can be cut or ripped from the

background material, as shown in Fig¬

ures 119 and 120. These suggestions are

intended only to inspire the beginner to

his or her own attempts.

116

Watercolor brush.

117 Felt-tip pen.

118 Wooden stick.

119

Cut from paper

without a pattern.

120

Torn from paper.

AESD

DMGR

DHGM

51