pull the edge of the brush at a steeper

angle (Figure 88).

When you make small sans serif let¬

ters, it is more convenient to draw all hori¬

zontal bars as vertical lines (Figure 89).

For the letter О use a mahlstick for

the vertical sections and form the round

parts using three strokes each. Hold the

brush at a slant and start with the almost

horizontal sections of the side parts. The

letters S, G, C, B, e, s, and с are con¬

structed in a similar manner (Figure 94).

The curve of letters like n, m, b, and

h consists of two strokes, both executed

with a slanted brash (Figure 95).

Use a brash with stiff bristles for let¬

ters with stroke widths of more than 3Л

inch (2 centimeters). With some practice

it is possible to draw the round sections

freehand in sections of a quarter circle

each (see Figure 102).

Even-stroke Sans Serif Roman

Uppercase Letters

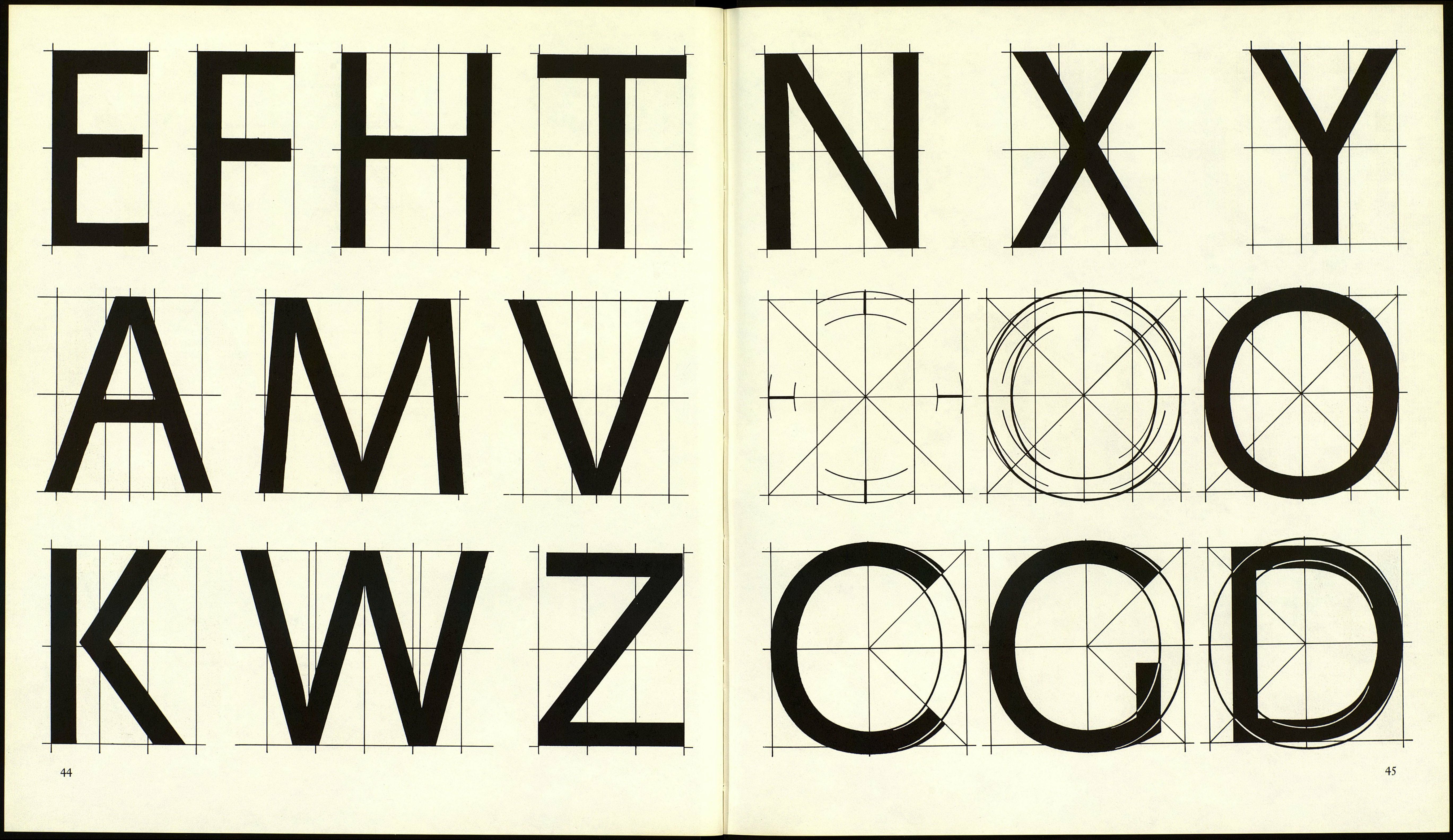

Drawing versus Constructing. The square,

triangle, and circle supply the basic

shapes for the Latin alphabet and the

roman letters of even stroke width are a

prime example. Since there is no rhyth¬

mical change between thick and thin

lines, no serifs or other decorative ele¬

ments, even beginners have no difficulty

in recognizing the proportions of the

letters. Figure 101 serves as nothing

more than a starting point. Take a soft

but well-sharpened pencil and practice

drawing the letters on graph paper until

the proportions seem right (Figure 99).

Now let us take a closer look. The con¬

struction process itself is not the aim of

the exercise, but merely a vehicle. The

shapes cannot be forced into a mold;

they should develop naturally, and a

system of construction rales is helpful

in the process.

Attempts at the geometric construc¬

tion of letters with ruler, compasses, and

measurement units have been made since

the Renaissance. We find well-known

examples of such letters in Pacioli's

Divina Proporzione (1509), in Dürer's

Unterweisung der Messung (1525), in the

Romain du Roi from the end of the seven¬

teenth century (Figure 97), and in the

sans serif of the Bauhaus artist Herbert

Bayer (Figure 98). None of these attempts

produced an aesthetically satisfying re¬

sult. Form develops out of movement,

which can only be stifled by excessive

construction. The act of writing is the

basis of every letter; organic movement

is the essence of its form. Complex low¬

ercase letters in particular defy strict

construction rales, and the only reliable

guides are examples, experience, and a

trained eye.

Draw your letters about 2Vt inches (6

centimeters) high. Choose a stroke

width of at least one tenth of the height,

but not wider than one sixth of it. Wider

strokes would destroy the classic pro¬

portions of a sans serif roman letter.

Extremely wide strokes would require

a change in the width of the letter in

relation to its height (Figure 100). The

letters E and В will thus appear as wide

as H and Z. A combination of both

would be stylistically unacceptable.

Draw straight lines with a ruling pen

and fill them in with a brash. If you con¬

struct curves with compasses, do not

forget to correct the shape (Figure 102),

and take into consideration the remarks

on optical illusions in Chapter 1. You

will achieve the best results with curved

letter parts if you draw them freehand

with a brash.

Figure 96

i b с d с f

8 h i 1

i --¿j:ifp ' у

Sixlllp: 4

::::х:И B: 6

И:: 7

I IS _ ÍÜ '■•■""~-t ~t*'

) -------Щ'-Щ

4 - --f" --(В ~ x Ü

i ----- jf:f ::j

6......Д.І...

- -j- - - - ig"-4------

8 - = :|;Í|Í;j:

a b с

d с f

S h i

Figure 97

abcdefghi

j^lmnopqr

STUVUJXyZ

Figure 98

wrong

Figure 99

Figure 100

right

BEEE

42

On page 42:

96 Construction of a Renaissance capital

letter. From Schreibbüchlein by Wolfgang Fug¬

ger.

97 Drawing from Romain du Roi, 1692.

98 Experiment in lettering by Herbert Bayer,

about 1926.

99 Drawing a letter.

Dilli

iiiïi

DHHH

Figure 101 on this page

Figure 102 on pages 44, 45, and 46

43

II