letters, or minuscules, should be one-

eleventh to one-twelfth narrower than

that of the uppercase (see Figure 34).

We will begin with the uppercase О

and H and with the minuscules m and o.

On these letters the width of the vertical

and horizontal strokes, the width of the

internal space, and its relation to the

height of the letter will be established.

A tall and narrow letterform usually ap¬

pears more elegant than a heavyset and

wider one. The space between verticals

should either be slightly wider or slight¬

ly narrower than the stroke width (Figure

84). If this rule is ignored, the image will

flicker in front of the viewer's eyes. Re¬

member the discussion on the relationship

between black and white areas of equal

size in Chapter 1. If the lettering is white

on black or any other colored ground,

adjust your measurements accordingly.

For the first exercise choose a space

between letters that is narrower than the

stroke width; this arrangement makes

proportions clearer and easier for begin¬

ners to handle.

Draw the horizontal lines somewhat

thinner than the verticals. In round parts

keep the upper and lower parts narrower

than the side parts (see Figures 29, 30,

and 32).

It is likely that you will have to make

several attempts at the shapes of H, O,

m, and о before you reach a satisfactory

arrangement of stroke widths and space

between letters and before you can pro¬

ceed to other letters.

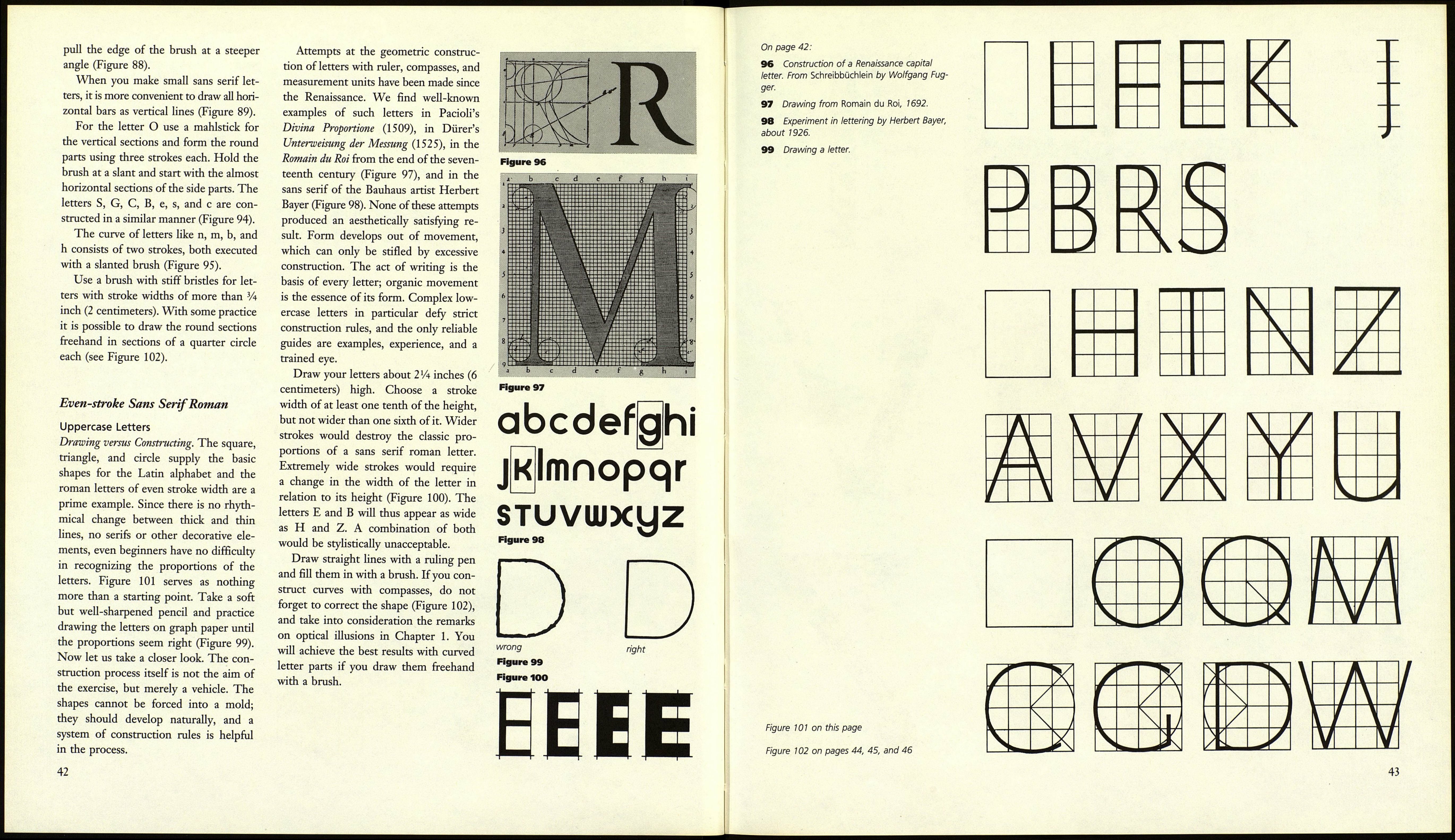

Naturally you have to adapt the con¬

struction scheme for the letters A, V, M,

N, v, and w with respect to their widths.

Letters that are made up of several

strokes appear darker than letters with

fewer strokes. A letter В will require a

thinner vertical line than a J, I, or L.

The inner diagonals of N, M, and W

have to be considerably thinner than the

outer lines. The area along which a ver-

40

tical and a diagonal line meet should be

as wide as possible. This creates space

for the interior angles and avoids dark

spots in the design. Figure 86 illustrates

this principle. For the same reason an¬

gles should be drawn with exaggerated

points (Figure 85 and see Figure 35,

page 22). It is a characteristic of the con¬

densed sans serif that there are many

transitions between straight and rounded

forms. The effect of this typeface de¬

pends to a great deal on the successful

management of these transition points

(see Figures 36 and 37).

The point at which the curved part

meets the main stem is of special impor¬

tance in letters like n, b, and h (Figure

86). Keep the angle deep enough to be

visible in a photographic reduction of

the letter to a size of 3/ie inch (5 mil¬

limeters). Use a reducing glass.

A number of optical illusions and

other problems may arise which cannot

be understood in depth until the student

has progressed further. Figure 82 shows

a well-developed alphabet of condensed

sans serif. The designer here deviated

in several instances from the original

scheme, but for the beginner it is useful

to identify the already discussed points

and to pay close attention to careful

drawing and cutting.

When cut letters rest loosely on a

surface, they will produce shadows along

some of their edges. Cover them with a

sheet of glass for more precise control.

Work on the letters in the following

sequence: H, M, E, O, A, N, U, B, R, S,

h, m, n, r, u, o, b, e, a, s, g. Manipulate

these key figures until they satisfy your

demands with respect to stroke widths,

relationship of shapes, and width of the

letters. Frequently it is necessary to draw

several versions of a letter and decide

from the interaction with other letters

which version is the best one. Arrange

your cut letters into words before you

On page 41 :

90 a and b Holding a mahlstick: different

finger positions.

91 Drawing a line with a mahlstick on a hori¬

zontal surface.

92 Drawing a line with a mahlstick on a wall.

93 How to hold a flat-tipped brush.

Figure 87

Figure 88 Figure 89

n

Figure 92, Figure 93

Figure 95

[Tfi

glue them in place, and check their size,

proportion, relationship to each other,

gray values, and their overall beauty.

No single letter should stand out as a

strange element.

Use gum arabic to glue the letters

down. It will not cause the paper to

expand and later contract in wrinkles,

because it will not be absorbed. Apply

the adhesive only on strategic spots and

you will be able to make changes if neces¬

sary. Visible spots of gum can be re¬

moved with an eraser.

Lettering with a Flat Brush

A flat brush is an appropriate instrument

for lettering condensed sans serif. Use a

mahlstick to draw straight lines. The

technique for using it on a vertical or

horizontal surface varies, and may pose

problems for the beginner, but it is ad¬

visable to attempt the method shown in

Figures 91-93, since this will be most

useful in the long run. A horizontal sur¬

face should be brought to an angle of at

least 30 degrees. Wrapping paper is the

most convenient material.

Start by practicing strokes in the size

and width of an I. Hold the edge of the

brush horizontally when you draw a

vertical line; hold it almost vertically or

slightly slanted when you draw a hori¬

zontal line. Draw the beginning and end

part of the strokes securely and with de¬

termination. Subsequent attempts to patch

a timidly drawn area will always be visible.

Use the mahlstick at a slant for

diagonals and finish the corners at the

end. The edge of the brush can also be

held horizontally from the beginning of

the stroke to the end. Some pressure or

a second stroke, slightly overlapping the

first, may be necessary to achieve the

desired width (Figure 87).

The letters M, W, and N present spe¬

cial situations because their inner diag¬

onals are narrower. Here you have to

41