INTRODUCTION

"Art takes time, and those who wish for

quick results had better not start. Good

lettering is, as a rule, created slowly.

Only the master can, on occasion, work

quickly; that is what makes him a master.

Lettering, like all art, is not for the

impatient."

These words of the famous typog¬

rapher Jan Tschichold1 head this chapter

to emphasize that success is achieved

only by a consistent and patient student.

One or two repetitions of the recom¬

mended exercises will not suffice. They

have to be done over and over again;

in addition, if you are a beginner, you

should devise new drills for every al¬

phabet until you master all forms with

ease. It would be detrimental to drop

a difficult or boring section of the in¬

troductory course to get to the next

exercise or a new alphabet. A constantly

changing point of view does not foster a

solid understanding of shape and form.

Basic forms have to be mastered before

derivative forms can be tackled. Only

this sequence makes the learning process

simple.

Mastering the basic forms, however,

should not be the student's only goal. Of

equal importance is the layout of the

entire page, requiring coordination of

many elements of graphic design. Sim¬

ple exercise pages, trial applications,

calligraphy, decorative arrangements of

letters, monograms, symbols, labels,

designs for posters, book covers, record

sleeves, and many other projects should

be approached in this way. Every unit

should be followed by appropriate appli¬

cations of the newly learned material.

1. Jan Tschichold, Treasury of Alphabets and Letter¬

ing. Reprint. New York: Design Press, 1992. Copy¬

right © 1952, 1965 by Otto Maier Verlag,

Ravensburg.

65 Renaissance scribe.

Figure 66

Figure 67

32

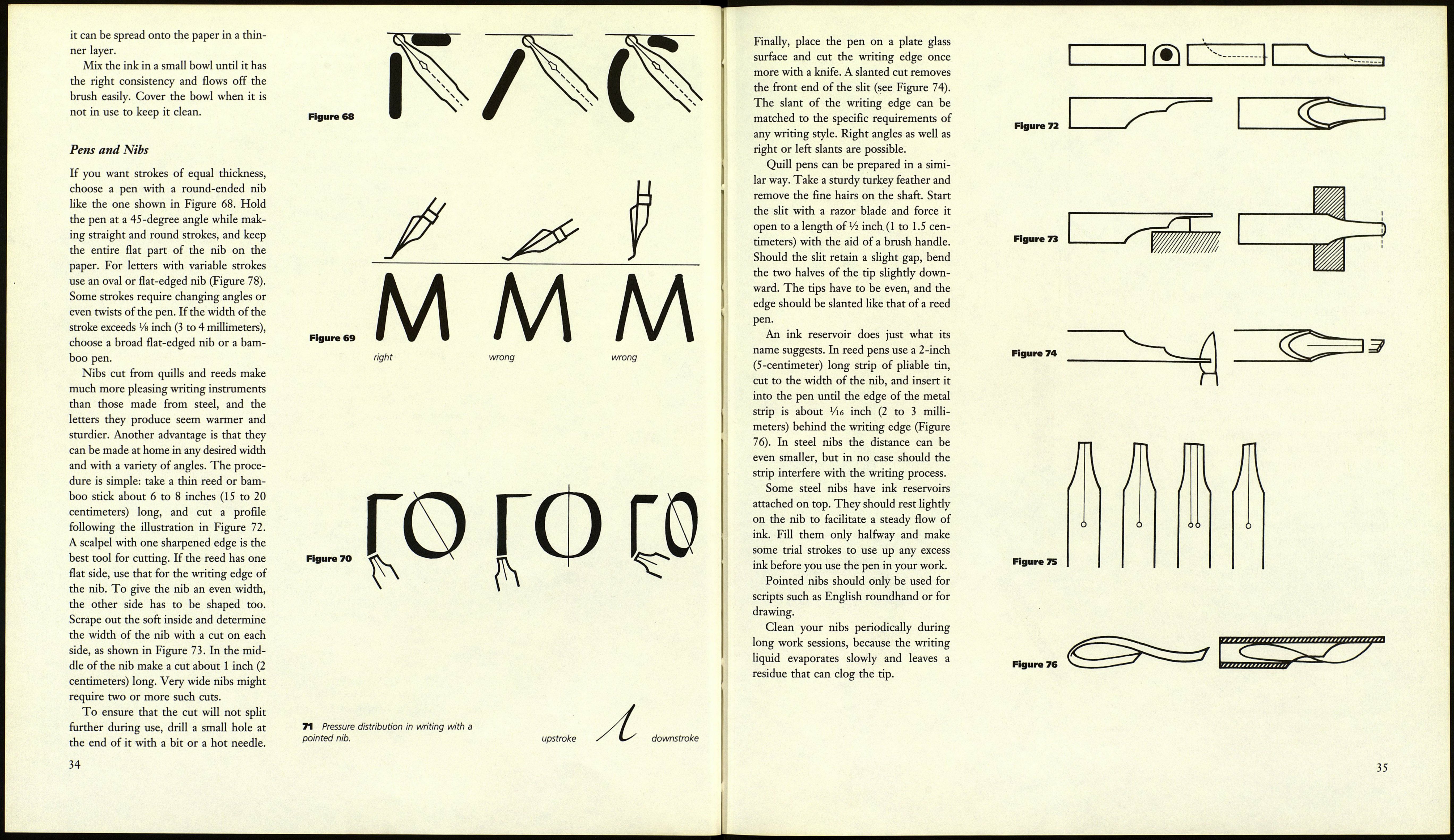

WORK SPACE, MATERIALS,

AND TOOLS

The Work Space

Medieval scribes worked at desks with

a slanted surface, which allowed an up¬

right and unencumbered posture. Such

an arrangement also affords a better

view of the page and lets the ink flow

more slowly from the nib. The desir¬

able angle of 30 to 40 degrees can be

achieved by fixing a board in the right

position, as shown in Figure 66, or by

tilting the entire table. For drawing, a

smaller angle can be used. The work

area should be about 24 by 36 inches

(594 by 841 millimeters), large enough

to support both elbows.

Only while guidelines are being

drawn should the paper be fixed to the

board; while you are lettering it has

to be movable. Stretch a strip of paper

across the board as protection from your

hand, position the loose writing paper

underneath and move it up as each line

is completed (Figure 67). You will

choose the height of your letters by ex¬

perience. An inkwell and a brush to fill

the nib are positioned at the left side of

the drawing board. The left hand holds

the brush to fill the nib of the pen,

which is moved to the left side and

remains in the right hand. The light

source should be at the left side or in

front of the writer. (Reverse these direc¬

tions if you are left-handed.) Tools in

good condition and a neat work space

are essential for success.

Paper

You will need good-quality paper that is

woodfree, will not let ink bleed through,

contains the right amount of size, and is

not too smooth. If the pen cannot be

moved freely across the surface, the

paper is not smooth enough. Do not use

tracing paper. Among the best choices

are book printing paper or Ingres paper.

The popular watercolor papers are not

suitable for writing, because their sur¬

faces are too rough. The best paper size

for practice sheets is about 11 by 14

inches (297 by 420 millimeters).

For drawing projects use a sturdier

white, smooth, woodfree paper that can

withstand the abrasion of erasers.

Never roll up either unused sheets of

paper or finished work for safekeeping.

It is best to keep them in folders and

store them horizontally.

Ink

Use ink that covers the paper well, flows

easily from the nib, and does not clog

it. For beginning exercises use black ink

only, because it makes errors more easily

visible than lighter shades or other col¬

ors. Many commercial liquid inks are

available: be sure the brand you choose

will not corrode your pen nib, clog it, or

produce fuzzy and imprecise lines. The

best choice is a solid block of Chin¬

ese ink, which has to be prepared with

water on a slab of slate before it can be

used. Once dried, this ink crumbles and

cannot be used again. Prepare small

amounts and replenish the supply fre¬

quently. Black watercolor may rub off,

but can be used if water-soluble glue is

added. If you add prepared Chinese ink

to watercolor you will get a very deep

velvety tone of black. Add small amounts

of ocher or red to your ink instead of

using pure ink for any project other than

exercises.

Draw with tempera or gouache colors

and add water-soluble glue if necessary.

Small and delicate embellishments are

best drawn with Chinese ink, since it

is composed of particles that are more

finely ground than other pigments, and

33