letter В appears darker than the letter E.

An experienced letterer will narrow the

vertical lines of the В and slighdy widen

those of L or I to balance. Follow the

same principle for roman letters.

Figure 33 shows that a short vertical

bar appears thicker than a longer one of

the same width, which is why it is neces¬

sary to draw short verical parts of letters

with slighdy thinner strokes. For the

Figure 33a

same reason, all lowercase letters should

be constructed with thinner verticals

than uppercase letters (Figure 34). The

larger interior space of uppercase letters

also necessitates different stroke widths.

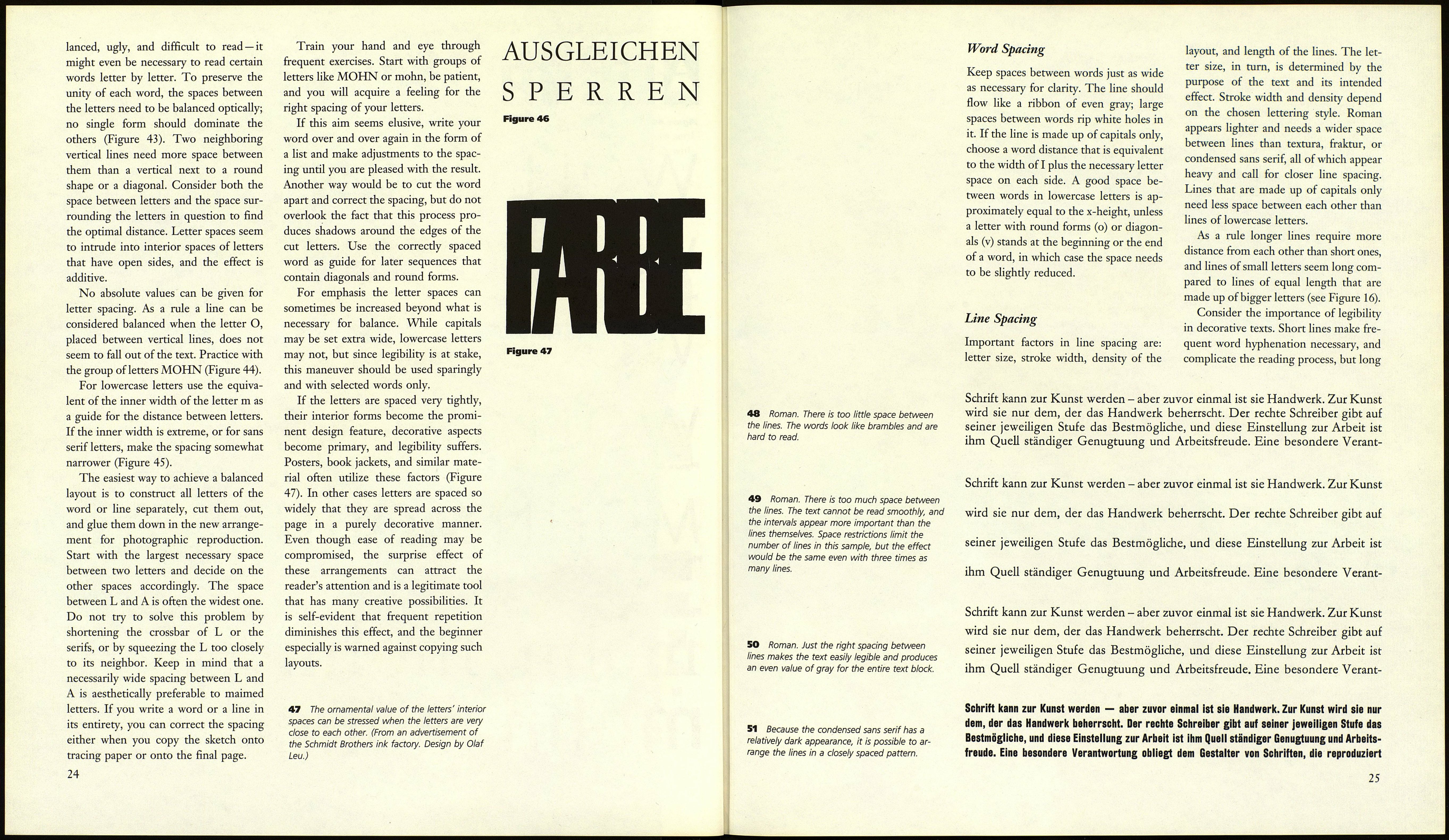

When two diagonal strokes intersect,

a black spot results and draws undue at¬

tention. Counteract this effect by deeper

cuts or angles at these points (Figure 35).

The transition from straight to round

lines also presents problems. The careful

observer can detect a break in the line if

the round section was constructed with

compasses. Sacrifice the perfect geomet¬

ric form to a gradual change in curvature

(Figure 36).

If you construct condensed sans serif

capitals such as O, C, G, and D with

compasses and ruler, the straight lines

will appear slightly concave. To make

GICHn

Figure 33b

Figure 34

Figure 35

Figure 36

Figure 37

Figure 38

Figure 39

+

+

22

BQBBHHñBG

Figure 40

Figure 41

WOLLGARNE

II - l..... I I I Г l Г I г^

wow

Figure 42

WOLLGARNE

Figure 43

MOHNMOHN

Figure 44

Figure 45

mohn mohn

mohn mohn

them look straight, draw them with a

slight bulge towards the outside (Fig¬

ure 37). Similarly, letter parts that are

geometrically perfectly straight will

seem thicker in the middle, but if you

narrow the verticals in the midsection,

the sides will appear parallel (Figure 38).

The smaller a form is, the rounder its

corners will seem (Figure 39).

LETTER, WORD, AND LINE SPACING

Letter Spacing

Letters are arranged next to each other

as words and lines, lines are combined to

make text blocks, and all are elements of

the page layout. It would satisfy neither

the demands of legibility nor of aesthet¬

ics to string one letter after another

without further thought. Empty spaces

inside the letters and the area surround¬

ing them all have specific ornamental

values, and the designer has to deal with

them (Figures 40 and 41). Spaces can be

neutralized or activated through man¬

ipulation; more information on this can

be found at the end of this chapter.

It is necessary to render the interior

spaces of letters optically neutral to

achieve clarity. If all spaces between let¬

ters were exactly equal (Figure 42) or if

they were decided in an arbitrary way,

areas of concentrated color would ap¬

pear on the page. Letters such as О, C,

G, on the other hand, would create

holes, and the surrounding spaces of

L, T, A, V, P, and others would act in a

similar way. The result would be unba-

42 Letters with equal spaces between them.

43 In a well-balanced word the spaces be¬

tween letters are optically balanced.

23