Lettering on Walls

The range of choices is determined by

the type of material at hand. Lime, ce¬

ment, or mixed grounds, if they are new,

can be treated in fresco or sgraffito tech¬

nique. The structure of the surface

should be as smooth as possible. In in¬

dustrialized areas air pollution will attack

the surface of frescoes and eventually de¬

stroy them. Match colors to the content

of the ground — chalk, latex, oil, emul¬

sions, and mineral pigments all have spe¬

cific requirements, and their proper

management falls in the realm of pain¬

ters. For high-quality lettering it is

necessary to collaborate with painters,

who are not usually trained in lettering

design, and combine the specific skills of

graphic designer and painters. The

graphic designer will be responsible for

the choice of type and the arrangement

of letters and will produce a design as

well as a pattern drawing on paper, ide¬

ally in full size. He or she will also discuss

the colors and their technical require¬

ments with the workman, and assist in

the mixing of color samples.

Sgrafßto.15 Of all mural techniques,

sgraffito is described in detail because it

requires more than a simple transfer of

the design onto the ground, and it is dif¬

ficult to find specific instructions for the

process.

The earliest sgraffiti (sgraffiare — to

scratch) date from the Renaissance and

are found in northern Italy as weather-

resistant murals. The German architect

Gottfried Semper reintroduced this nearly

forgotten technique in the nineteenth

century for decorating the outside of

buildings. Modern architecture avails it¬

self of this technique for lettering on

facades or interior walls. It is, however,

15. Dr. Gerhard Winkler, Leipzig, was consultant

for this section.

208

necessary that the entire wall surface be

applied at the time of lettering.

The technical requirements must be

considered from the start. No intricate

details are possible; fat-face types cannot

be used because their thin strokes do not

withstand the weather well. Consider

the optical effect of shortening in per¬

spective, which can change the appear¬

ance of letter parts, especially when they

are thin.

It is best if the graphic artist person¬

ally transfers the design onto the wall

rather than leaving this job to workmen.

Beginners are advised to practice cutting

and scraping on sections of plaster. The

preparation of the wall itself and the

necessary material are best left to the

trained craftsman. The ingredients of

the plaster are slaked white lime and

sand, preferably washed river sand. The

sand should not contain clay and other

impurities, which may affect the firm¬

ness and color of the plaster. Lime and

sand are mixed in the proportions 1:3,

with slightly more lime for the first layer

than for succeeding ones. A small amount

of cement is added for exterior work. All

pigments used have to be lime-proof:

test before you start work by mixing the

paint with white lime and exposing it to

sunlight while wet. Some pigments may

contain ingredients that cause the plaster

to dull or bleed or develop a whitish

film. Unadulterated pigments are the

best choice. Many oxides are on the

market, but experience shows that earth

pigments last longest. These circum¬

stances restrict the available palette to

the following colors:

Yellow: yellow ocher, sienna

Red: burnt ocher, burnt sienna, En¬

glish red, red bole

Brown: umber

Blue: blue verditer

Green: green earth, green umber

Gray: slate gray

Black: vine black

Do not use more than one part pigment

to two parts plaster, for exterior or in¬

terior walls.

The tools used are wire loops and im¬

plements for scratching in different

widths, and these are available in stores

or can be improvised or made by any

smith (Figure 443).

Apply only as much plaster as you can

finish working in one session, and pro¬

tect outside walls during this time from

sun and rain with a tarpaulin. If you have

a choice, do your work during spring or

fall when air humidity is high, and avoid

work during very dry periods or under

intense sun.

The actual steps are as follows. A base

layer of mortar is applied to the wall,

with areas that are designated for the let¬

tering left half the thickness of the other

parts. The base layer must be left to dry

thoroughly and rewetted before the col¬

ored layer, about 'Л inch (5 millimeters)

thick, is applied. If additional layers of

color are desired, about two hours' dry¬

ing time should be allowed for each

layer. Finally, the layer of facade plaster

is applied. During the drying process a

thin transparent skin, or sinter, will form

on the plaster and the color will brighten,

which makes it possible to create letters

by scratching off the lighter top layer

even if no colored layer was placed un¬

derneath. This sintered layer also makes

later corrections impossible. If you trans¬

fer your design in the traditional way

with charcoal and pounce bag, the re¬

sulting dots will be incorporated in the

sinter and have to be removed during

cutting. It is therefore better only to

press the lines through. If the work time

exceeds ten hours the surface may begin

to chip. The sgraffito is done either by

cutting the letters into the plaster, to

make recessed colored letters, or cutting

away the surrounding area, creating

white raised letters on a colored back¬

ground. The scratching should only be

deep enough to expose the top of the

colored layer. The lower edges on letters

that are exposed to the elements must be

beveled to keep water from collecting in

the corners (Figure 444).

Lettering Design for Stone Carving16

Lettering on stone for memorial tablets,

gravestone markers, and plaques on pub¬

lic buildings is the specialty of stone ma¬

sons. Unfortunately most of them have

little or no education in the field of type

design and often choose the worst of a

limited and outdated selection of pat¬

terns. The graphic designer, on the other

hand, often has no concept of the special

requirements of the material or of the

chiselling process. Many drawn or writ¬

ten letters cannot be transferred to the

medium of stone, and what looks good

on polished granite might be impossible

on travertine. The following instruc¬

tions cannot turn a stone mason into a

graphic designer or vice versa, but they

might further understanding of basic

procedure to make productive coopera¬

tion possible.

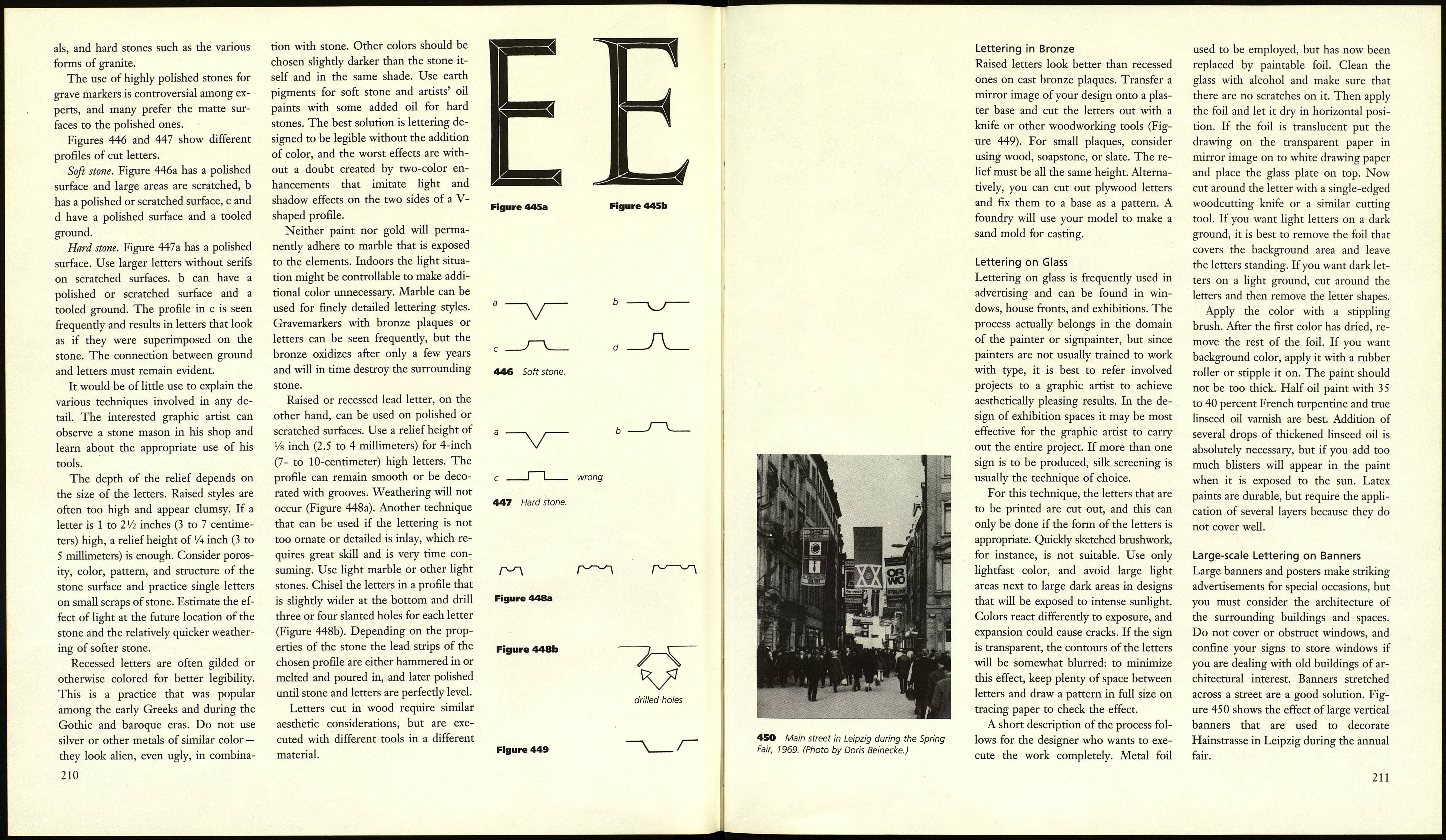

Best suited for letters cut in stone are

the letters that we find on monumental

inscriptions — roman capitals, sans serifs,

and faces with little contrast in the

stroke widths (Figure 445a). The capitals

of Gill Sans are a good example, if the

M is slightly modified. Frequent models

are the capitals of the Trajan Column

with their pointed serifs and light con¬

trasts in stroke width (Figure 445b).

Other good choices are capitals of other

condensed sans serifs if the stroke width

is fairly narrow. Both raised and recessed

versions are possible. The use of roman

16. This section was written in cooperation with

the sculptor Fritz Przibilla, Leipzig.

lowercase, however, is questionable, be¬

cause these letters were developed as

bookhand, and the chisel would have to

imitate the movements of the pen. Lower¬

case roman letters are neither simple

enough to be monumental, nor rich

enough in detail to be decorative. All

other styles that developed their charac¬

teristics from the motion of the pen

stroke are equally unsuited to transfer

into stone.

A possible exception are the baroque

italics and fraktur styles of the thirteenth

to seventeenth centuries. They can be

found on old grave markers and have

great decorative appeal. Their details

lend themselves to the expressive range

of the stone mason's tools. The stones

themselves were often round in shape

and their surfaces slightly convex. Tex¬

tura was usually worked in raised letters,

fraktur and italic recessed.

Old graveyards and churches are rich

sources of inspiration for the student of

historic lettering styles. Rubbings can be

taken by taping paper over the stone and

rubbing with the flat side of a piece of

chalk or wax crayon over the letters until

their shapes become visible on the

paper.

The following alphabets in this book

are suitable for work in stone: Figures

82, 102, 188, 189, 351, and 358.

When you design a text for a stone

cutting, keep in mind that your tool is a

chisel with a specific range of possibilities.

Draw the contours of the letters only on

tracing paper and leave detail forms to

the mason. Specify the format and the

placement of the text on the stone. Short

inscriptions look best in a symmetrical

arrangement: longer text should be set

flush left. Let the mason transfer the text

onto the stone.

There are two categories of stone:

soft stones such as sandstone, limestone,

and marble, and artificial stone materi-

209