will be heavier than expected. High-re¬

solution devices solve these problems.

The flexibility and malleability of

phototype has been extended by computer

type. But the problems of good letter- and

word spacing still remain. Computer

memory and power is often an impedi¬

ment to creating all of the necessary re¬

finements for the myriad letter combi¬

nations found in languages that use the

roman alphabet. The shoulders, set

widths, duplexing, unit widths, and

other type body parameters built into

earlier generations of typesetting equip¬

ment may have created limitations and

compromises, but they set overall stan¬

dards that were easy to maintain.

An offshoot of the shifting nature of

computer type is the ease with which it

can be created, edited (as distinct from

manipulated), and distributed. Anyone

with a computer and one of several typo¬

graphic software packages such as Altsys's

Fontographer, Ikarus-M, or Letraset's

Fontstudio, can change existing type¬

faces to suit their preferences and pre¬

judices. They can also create their own

typefaces. The type designer and man¬

ufacturer, once united in the person of

the punchcutter, are reunited. Editing

and creating can be done with both bit¬

mapped and outline fonts, though the

latter are more flexible. It can even be

done using non-typographic software

such as Adobe's Illustrator 88 or Aldus

Freehand, since type is now a graphic

element.

Special Techniques

Woodcuts and Wood Engravings

Both woodcuts and wood engraving are

relief printing processes, which means

that the image to be printed is left on the

surface of the wood, while all other parts

are cut away. The medium is a slab of

soft plank- or side-grain wood — that is,

200

wood cut along the grain —for wood¬

cuts. Endgrain wood is used for engrav¬

ings; the fibers are cut across the grain.

Woodcuts can be used to reproduce

lettering, but they are primarily a means

of artistic expression, since many other

superior techniques have replaced the

woodcut for the mere printing of type.

From our point of view, the inspiration

is usually a drawn or printed letter, but

the woodcut should go beyond mere im¬

itation in the use of materials and tools.

The cutting process changes the charac¬

ter of the letters and makes them look

rougher and angular. Attempts to re¬

create the pen stroke in detail interfere

with the particular expressiveness of the

medium. The initial design should antic¬

ipate the character of the finished piece.

Highlights in the history of woodcut

lettering are the stamps of the Far East

and Chinese block books, European

block books of the second half of the fif¬

teenth century, the woodcuts of the Ex¬

pressionists, and finally the works of

Rudolf Koch and the Stuttgart school

under Ernst Schneidler. Any designer

who wishes to master the intricacies of

woodcutting is well advised to study these

examples of the technique.

The ultimate effect of a woodcut de¬

pends largely on the materials used.12

Whether the wood is hard or soft, fine-

or rough-grained, the marks left by the

cutting tool, the finish and surface —

absorbent or polished, smooth or por¬

ous—of the paper, and the pressure

from the printing press or the artist's

hand determine the outcome.

There are two kinds of woodcuts —

the positive and the negative; the latter

is easier to handle and more satisfying

12. The following information on woodcuts and

endgrain carving is excerpted from the work of

Johannes Lebek, Holzscbnittfibel. Dresden: Verlag der

Kunst, 1962.

m

423 Woodcut of the artist's name, by Karl

Schmidt-Rottluff, 1920.

Ь ад pfetb modpbtn №ifV im

fbUe, und obgieid) der m\fr

eóien utîFtnr cut> fremh cm f(#)

bat, fb }ie% dnôfeU* pfetd

don> бел null mit gcc^«r ma/re

auf Ò&B felá, und dann itfñífjfí

daraus edler, fdjónec werfen

uno der «ole, Hiß« «vêtu, ter

min mer (o «mtrife, wore ¿er

Ttvijß- at'ff/t da- alfo htigs darrten

mi/bda$ find beine eigenen

д?Ьг«гІ)Чгі , die bu 4uty ab run

imo ablegen non) ubmmnden

hmtnír,- mu mtUj und rtrit fltifi

nuf den nefeer dift h'ebwitren

ttHÜcnfl softes m rtdnvr gtlaf-

ШIje'ir «У'лег fefb[> - rnulsr -

424 Woodcut by HAP Grieshaber, 1938.

for the beginner to work with.

Several types of wood can be used for

woodcuts: linden or pear and alder, even

though it splinters easily, and willow, pop¬

lar, birch, and maple. Even hard woods

like apple, cherry, and white beech can

be used, but pine should be reserved for

projects that incorporate its distinctive

graining. Boxwood is best suited for end-

grain carving. Other choices are pear,

apple, plum, white beech, lilac, and

hawthorn, as well as maple, soft birch,

large-pored cherry, and elderberry.

Preparing the Woodblock. Woodblocks pre¬

pared for printing are not readily avail¬

able, but a carpenter can do the job. The

wood has to be thoroughly dry, well sea¬

soned, planed by machine and by hand

with successively finer blades, and finally

smoothed with sandpaper. It is easier to

handle soft wood after a hot solution of

glue and water has been brushed on.

With a rag, apply a thin layer of fixa¬

tive, shellac, or varnish to avoid swelling

of the wood grain when you draw on the

surface with paint or ink.

Endgrain blocks are more difficult to

prepare. They often consist of several

pieces that may have to be assembled on

a lathe or with the help of a router.

Smooth the block with a scraper and fine

sandpaper, possibly with the addition of

a little oil, and wipe with a shellac solu¬

tion. Problem spots in the wood can be

drilled out by a carpenter and replaced

with a matching plug.

Transferring the Drawing. Draw directly

on the wood (remember that your de¬

sign must be a mirror image of the de¬

sired end result) or trace your design

onto the block using one of the follow¬

ing methods.

1. Draw the original design on tracing

paper. Apply a thin layer of varnish to

the wood surface and dust with talcum

powder. Put the paper on top face down,

tape it in place, and rub. The drawing

will appear in mirror image on the

block.

2. Draw your design in mirror image

on tracing paper and cover the back of

it with light-colored chalk. Roll a layer

of block-printing ink on the woodblock,

dust with talcum powder, and prick the

lines of the drawing through with a

needle.

3. Draw your design in mirror image

on tracing paper. Dampen it slightly and

adhere it to the block with thinned

waterproof glue. Rub the paper on sec¬

urely, so that it will not separate from

the wood during the cutting process.

Use this method only for woodcuts; it is

not suitable for endgrain carvings.

4. To transfer an image photographi¬

cally, prepare the block as follows. To

protect it from humidity, coat it with a

layer of shellac. On a sheet of glass mix

zinc oxide with the white of a fresh egg

and rub the mixture onto the block with

your hand. Let it dry and then sand it

lightly with fine sandpaper. Next, apply

a thin coat of photographic emulsion

under low light. Let it dry in a dark

place. Then put the film negative con¬

taining the design on the block, cover it

with a sheet of glass, and secure it with

clamps. Expose it to light; the time

needed is a matter of practice and ex¬

perience. To make the image on the

block permanent, develop it with photo¬

graphic fixer (hypo). Then rinse with

water and let the block dry.

If your design is very detailed, protect

the image on the block with a piece of

paper that you can tape around the

edges, and rip off the covering over each

sections as you are working.

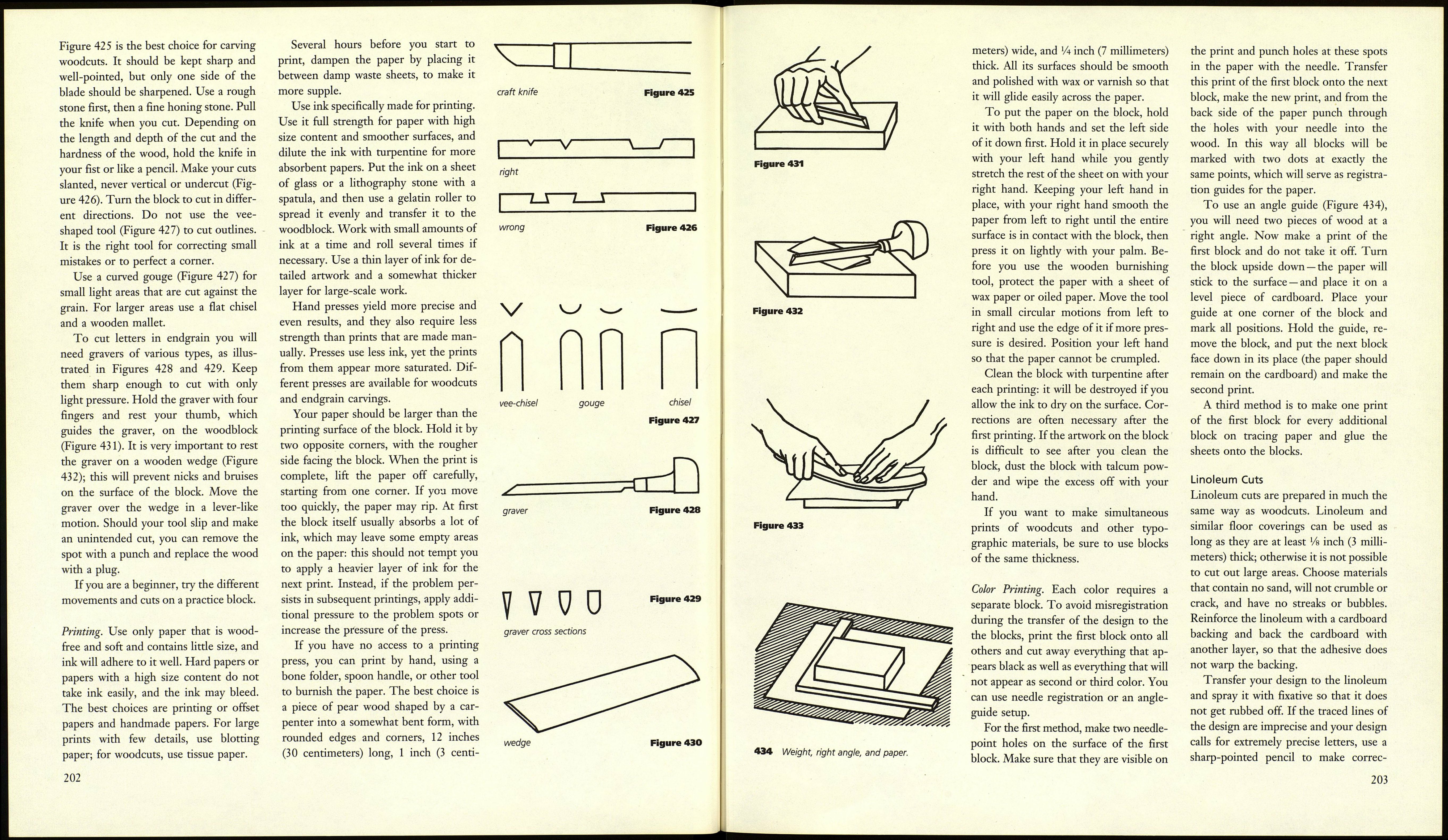

Tools and Techniques for Cutting. A wood¬

cutting knife, such as the one shown in

201