ORNAMENT

DECORATION HAS LONG BEEN CENTRAL TO ALL KINDS OF

DESIGN, REGARDLESS OF WHETHER IT IS TWO OR THREE

dimensions. Designers have had passions either for or against it.

For some, it is sublime; for others, it is a crime. Hot-metal type

foundries were the great purveyors of decorative material, pro¬

viding pounds of the stuff to printers large and small. Until the

European Modern movement of the early 1920s and its typo¬

graphic wing known as the New Typography banished orna¬

mental typographic devices from contemporary graphic design,

decorative borders and initial capitals were a primary element of

the printer’s visual lexicon.

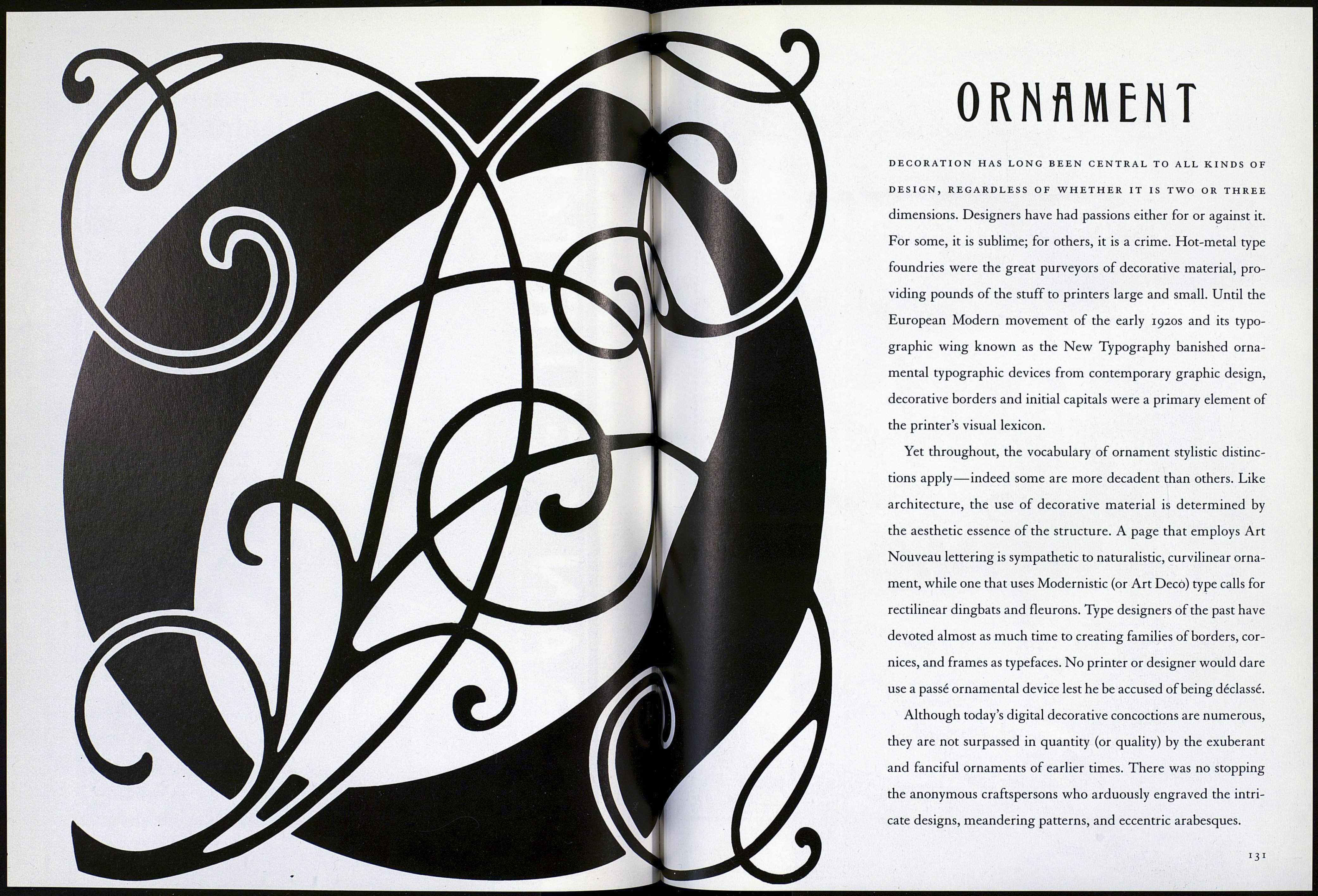

Yet throughout, the vocabulary of ornament stylistic distinc¬

tions apply—indeed some are more decadent than others. Like

architecture, the use of decorative material is determined by

the aesthetic essence of the structure. A page that employs Art

Nouveau lettering is sympathetic to naturalistic, curvilinear orna¬

ment, while one that uses Modernistic (or Art Deco) type calls for

rectilinear dingbats and fleurons. Type designers of the past have

devoted almost as much time to creating families of borders, cor¬

nices, and frames as typefaces. No printer or designer would dare

use a passé ornamental device lest he be accused of being déclassé.

Although today’s digital decorative concoctions are numerous,

they are not surpassed in quantity (or quality) by the exuberant

and fanciful ornaments of earlier times. There was no stopping

the anonymous craftspersons who arduously engraved the intri¬

cate designs, meandering patterns, and eccentric arabesques.

131