Fig. 7

■ I # 4 А T • ■ Il

■ I «Ufi ■ »I

■ I•>AT• MH

Fig. 8

any kind of scientific training failed to approach

people professionally engaged in the problems

confronting us. The answer is that we did as far as we

were able, but I'm afraid on the whole people are not

inclined to help if they do not think the project will

work or if they feel no necessity for it. Not so though

with Dr Quinn, at least he kept an open mind and

through his guidance and discipline we more or less

started all over again.

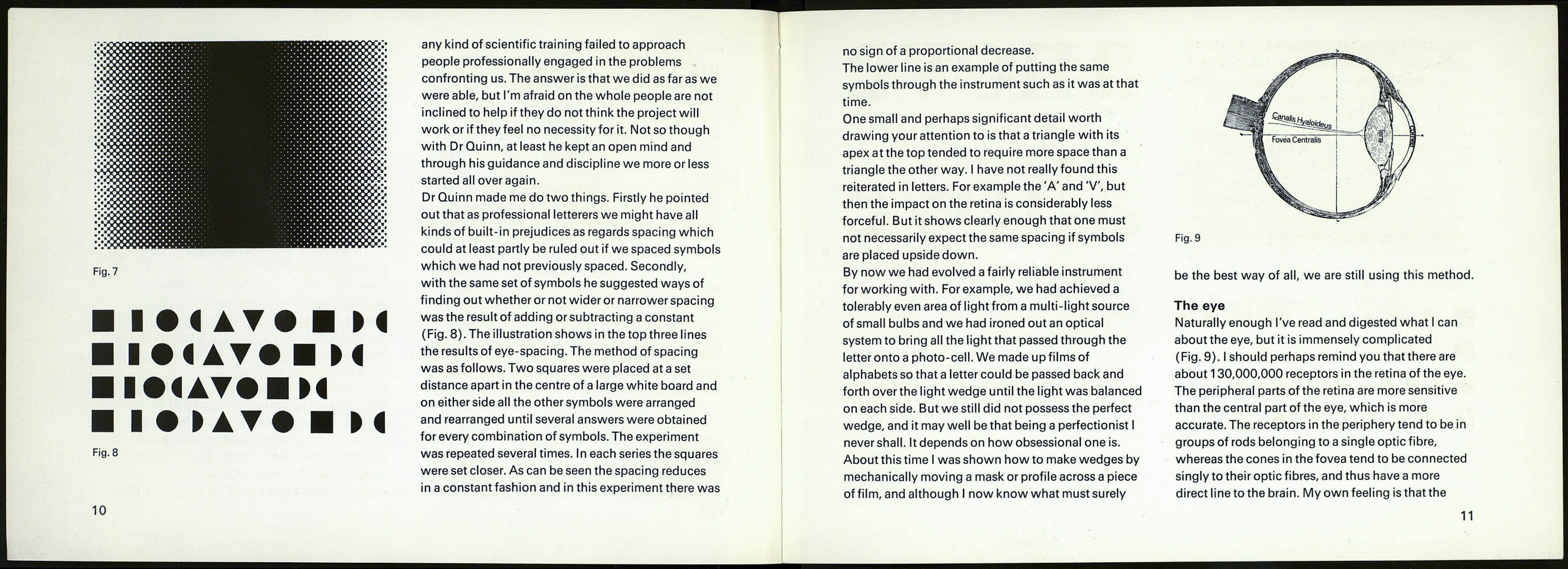

Dr Quinn made me do two things. Firstly he pointed

out that as professional letterers we might have all

kinds of built-in prejudices as regards spacing which

could at least partly be ruled out if we spaced symbols

which we had not previously spaced. Secondly,

with the same set of symbols he suggested ways of

finding out whether or not wider or narrower spacing

was the result of adding or subtracting a constant

(Fig. 8). The illustration shows in the top three lines

the results of eye-spacing. The method of spacing

was as follows. Two squares were placed at a set

distance apart in the centre of a large white board and

on either side all the other symbols were arranged

and rearranged until several answers were obtained

for every combination of symbols. The experiment

was repeated several times. In each series the squares

were set closer. As can be seen the spacing reduces

in a constant fashion and in this experiment there was

no sign of a proportional decrease.

The lower line is an example of putting the same

symbols through the instrument such as it was at that

time.

One small and perhaps significant detail worth

drawing your attention to is that a triangle with its

apex at the top tended to require more space than a

triangle the other way. I have not really found this

reiterated in letters. For example the 'A' and 'V', but

then the impact on the retina is considerably less

forceful. But it shows clearly enough that one must

not necessarily expect the same spacing if symbols

are placed upside down.

By now we had evolved a fairly reliable instrument

for working with. For example, we had achieved a

tolerably even area of light from a multi-light source

of small bulbs and we had ironed out an optical

system to bring all the light that passed through the

letter onto a photo-cell. We made up films of

alphabets so that a letter could be passed back and

forth over the light wedge until the light was balanced

on each side. But we still did not possess the perfect

wedge, and it may well be that being a perfectionist I

never shall. It depends on how obsessional one is.

About this time I was shown how to make wedges by

mechanically moving a mask or profile across a piece

of film, and although I now know what must surely

Fig. 9

be the best way of all, we are still using this method.

The eye

Naturally enough I've read and digested what I can

about the eye, but it is immensely complicated

(Fig. 9). I should perhaps remind you that there are

about 130,000,000 receptors in the retina of the eye.

The peripheral parts of the retina are more sensitive

than the central part of the eye, which is more

accurate. The receptors in the periphery tend to be in

groups of rods belonging to a single optic fibre,

whereas the cones in the fovea tend to be connected

singly to their optic fibres, and thus have a more

direct line to the brain. My own feeling is that the

11