fanciful Victorian diaplay types seem to sense the

need for bringing the optical centre over as near to

the mathematical centre as possible. The secret of a

good fit and an economical one lies precisely in

moving the optical centre towards the mathematical

centre.

This is only one way the machine has of influencing

the design of letters. Another is in guiding the

designer to produce a letter in complete accord with

its space

As I have already stated, the space allotted to any

character must ideally be an expression of that

character. Therefore it would also be true that, if the

space is predetermined, the letter must be an

expression of the space. In other words, the intensity

of two characters that are to occupy similar spaces

must be equal for the retina. This does not mean of

course, that the designs must be similar, but that their

weight expressed in moment terms around a centre

must be equal. If therefore it is desirable to produce

an alphabet with only six different unit widths, it is

equally desirable that the letters have only six

different weights, if spacing and colour are

considered important.

To be asked as a designer to alter his design from this

point ofview seems to meto be something he would

understand and wish to do. But to be told simply to

22

narrow or expand the letter to occupy a larger or

smaller unit width is not any longer quite good

enough, particularly when the end result does not

seem quite to justify it.

The influence of calligraphy

I have always been mesmerized by good calligraphy.

Not only is there the marvellous co-ordination of

hand, eye, and attention to watch in the good

calligrapher at work, but there is the further miracle of

spacing. We with predetermined letter forms have no

excuse for bad spacing - in theory we can move our

letters about until they look right, or do it all again.

The calligrapher must do it right the first time. And by

right we mean shape his letters and space them at the

same time. This he does in an apparently effortless

manner. What judgement I We have been talking

about putting any one letter in a passive position

between any two. The calligrapher has the very

remarkable talent of placing a letter where it will be in

the passive position between two, but only when he

has put down the third letter. Little things may please

little minds, but this certainly pleases me I To make

things still more complicated the calligrapher can

expand or condense his letter forms in the minutest

way in order to justify his text. Indeed in the last

analysis 'justifying' can only be done if everything is

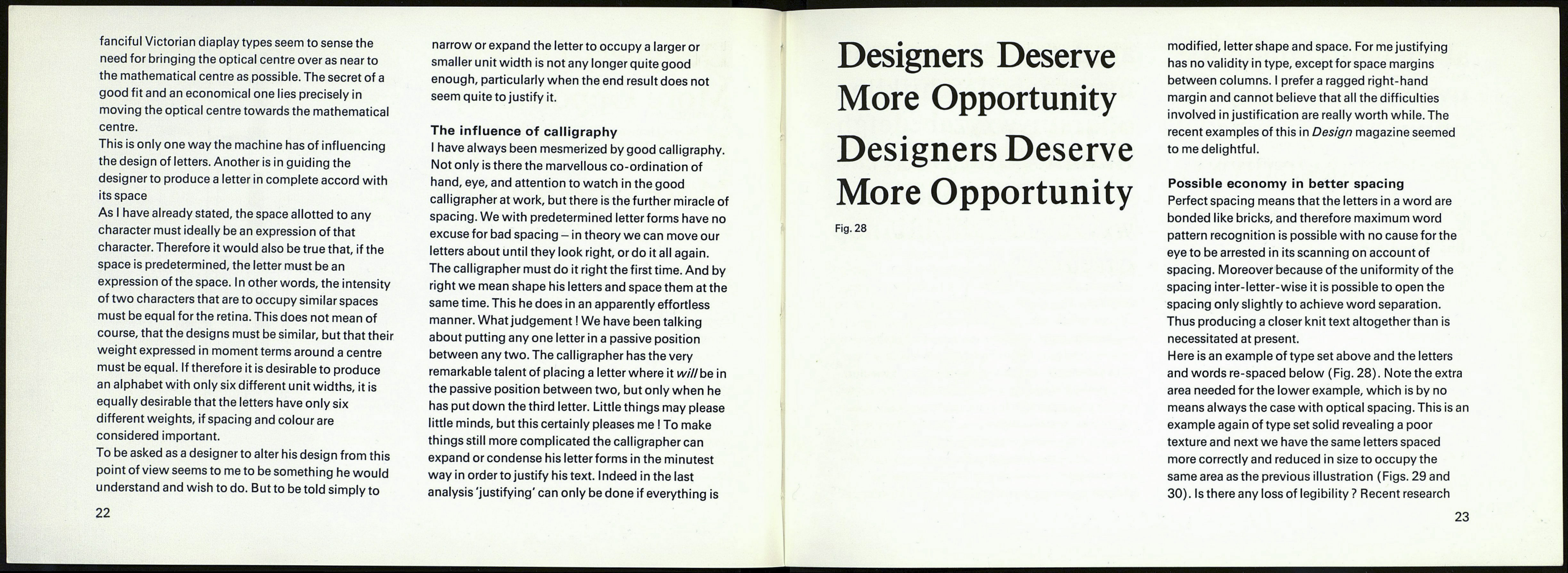

Designers Deserve

More Opportunity

Designers Deserve

More Opportunity

Fig. 28

modified, letter shape and space. For me justifying

has no validity in type, except for space margins

between columns. I préféra ragged right-hand

margin and cannot believe that all the difficulties

involved in justification are really worth while. The

recent examples of this in Design magazine seemed

to me delightful.

Possible economy in better spacing

Perfect spacing means that the letters in a word are

bonded like bricks, and therefore maximum word

pattern recognition is possible with no cause for the

eye to be arrested in its scanning on account of

spacing. Moreover because of the uniformity of the

spacing inter-letter-wise it is possible to open the

spacing only slightly to achieve word separation.

Thus producing a closer knit text altogether than is

necessitated at present.

Here is an example of type set above and the letters

and words re-spaced below (Fig. 28). Note the extra

area needed for the lower example, which is by no

means always the case with optical spacing. This is an

example again of type set solid revealing a poor

texture and next we have the same letters spaced

more correctly and reduced in size to occupy the

same area as the previous illustration (Figs. 29 and

30). Is there any loss of legibility? Recent research

23