4<э Art in the Alphabet.

really an equal-limbed 7 placed (as it would

naturally fall) so as to rest upon its two ends : it

is not the figure that is changed, but its position.

Much more puzzling is the early form of 4 (227,

228, 229), a loop with crossed ends upon which it

stands. The popular explanation of the figure as

" half an eight," is anything but convincing; and it

appears to have no Eastern prototype. There is a

17th-century version of it, however, in the Francis-

kaner Kirche, at Rothenburg (242), which, had it

been of earlier date, might have been accepted as

a satisfactory explanation. There the loop has a

square end, and the figure rests, not upon its two

loose ends, but partly on its point. Imagine this

figure standing upright, one point facing the left,

and it is seen to be a 4 of quite ordinary shape. This

may not be the genesis of the form ; but, if not, it is

ingeniously imagined by the 17th-century mason.

Writers have from the first made use of contrac¬

tions, the ready writer in order to save time and

trouble, the caligrapher, sculptor, and artist

generally, in order to perfect the appearance of

his handiwork, and, in many cases, to make it fit

the space with which he has to deal. The ends of

art are not satisfied by merely compressing the

letters, or reducing them to a scale which will

enable the writer to bring them all into a given

line (208). We, in our disregard of all but what

we call practicality, have abandoned the practice

of contraction, except in the case of diphthongs, and

Art in the Alphabet.

41

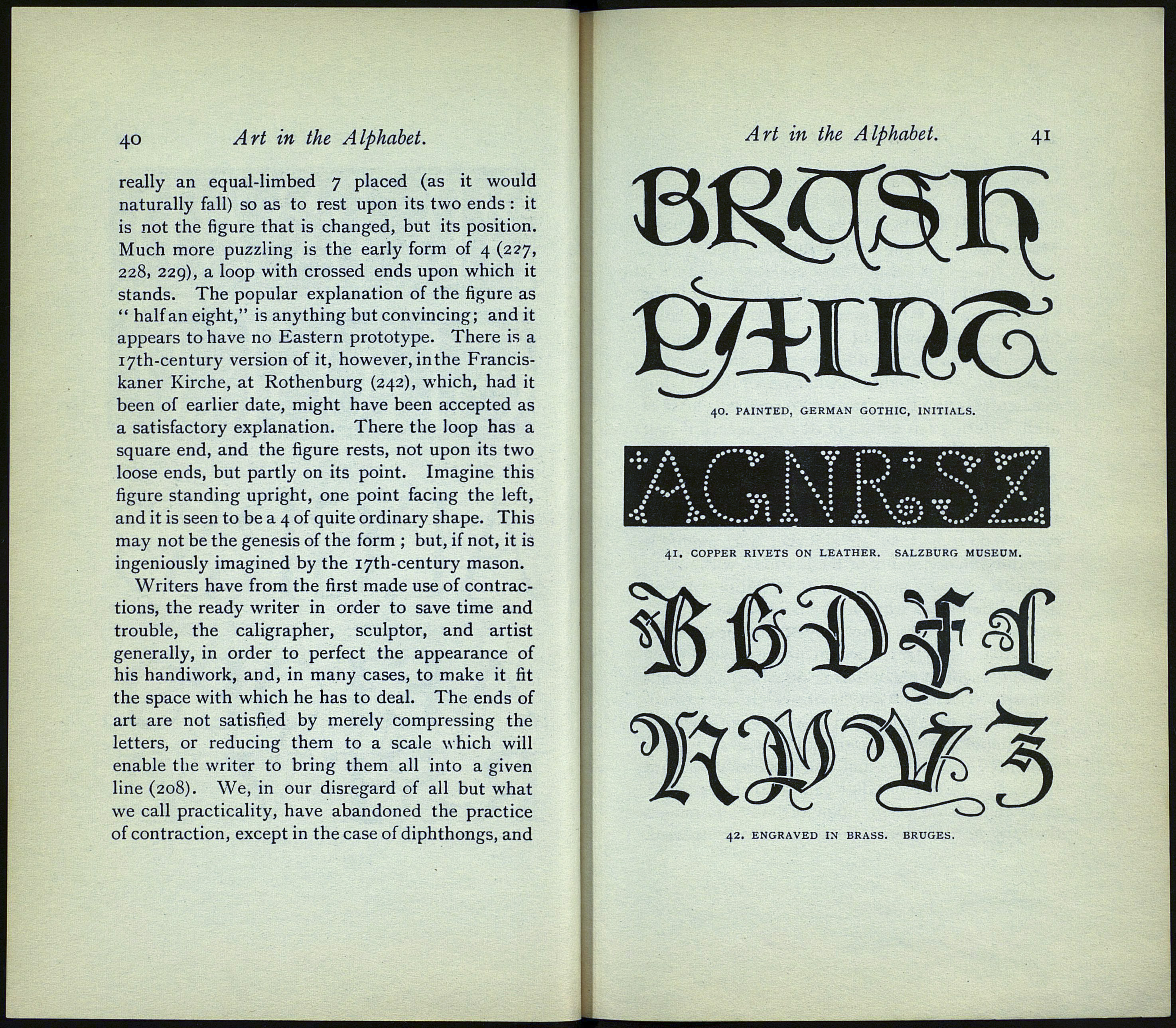

40. PAINTED, GERMAN GOTHIC, INITIALS.

41. COPPER RIVETS ON LEATHER. SALZBURG MUSEUM.

5

42. ENGRAVED IN BRASS. BRUGES.