Зо

Art in the Alphabet.

Even in late Gothic lettering we find a minus¬

cule which is of the pen (23), and another (24, 25)

which is monumental, adapted, that is to say, to

precise and characteristic rendering with the graver

upon sheets of brass. It is curious that out of this

severe form of writing the florid ribbon character

(108) should have been evolved. But when once

the engraver began to consider the broad strokes of

his letters as bands or straps, which, by a cut of

the graver, could be made to turn over at the ends,

as indicated in Alphabet 125, it was inevitable

that a taste for the florid should lead him to

something of the kind. The wielder of the brush

was in all times induced by his implement to make

flourishes (32, 33), in which the carver had much

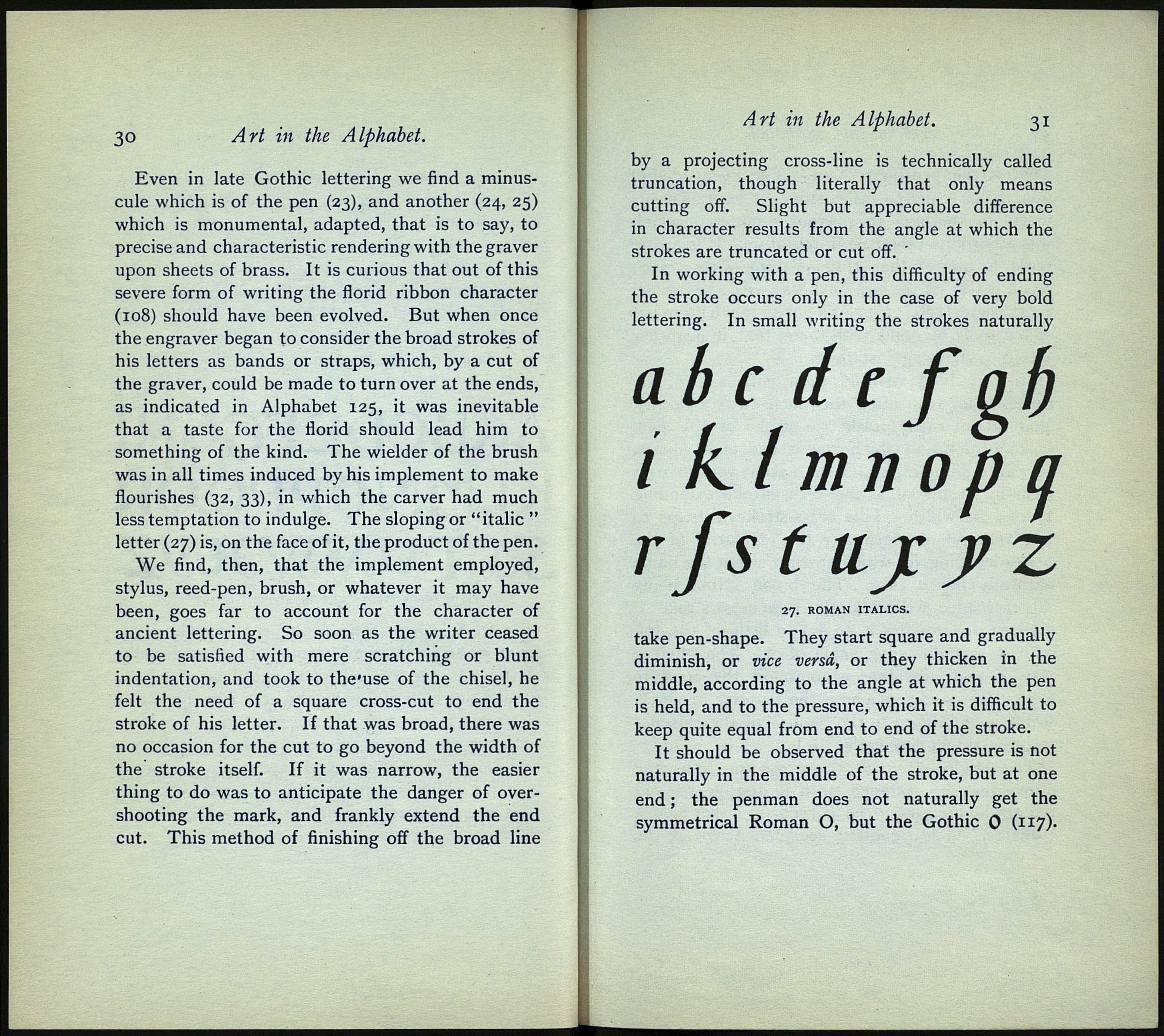

less temptation to indulge. The sloping or "italic "

letter (27) is, on the face of it, the product of the pen.

We find, then, that the implement employed,

stylus, reed-pen, brush, or whatever it may have

been, goes far to account for the character of

ancient lettering. So soon as the writer ceased

to be satisfied with mere scratching or blunt

indentation, and took to the'use of the chisel, he

felt the need of a square cross-cut to end the

stroke of his letter. If that was broad, there was

no occasion for the cut to go beyond the width of

the stroke itself. If it was narrow, the easier

thing to do was to anticipate the danger of over¬

shooting the mark, and frankly extend the end

cut. This method of finishing off the broad line

Art in the Alphabet. 31

by a projecting cross-line is technically called

truncation, though literally that only means

cutting off. Slight but appreciable difference

in character results from the angle at which the

strokes are truncated or cut off.

In working with a pen, this difficulty of ending

the stroke occurs only in the case of very bold

lettering. In small writing the strokes naturally

ab с dс f gb

i klmnopa

rfs t ujc j?z

27. ROMAN ITALICS.

take pen-shape. They start square and gradually

diminish, or vice versa, or they thicken in the

middle, according to the angle at which the pen

is held, and to the pressure, which it is difficult to

keep quite equal from end to end of the stroke.

It should be observed that the pressure is not

naturally in the middle of the stroke, but at one

end ; the penman does not naturally get the

symmetrical Roman O, but the Gothic 0 (117)-