го Art in the Alphabet.

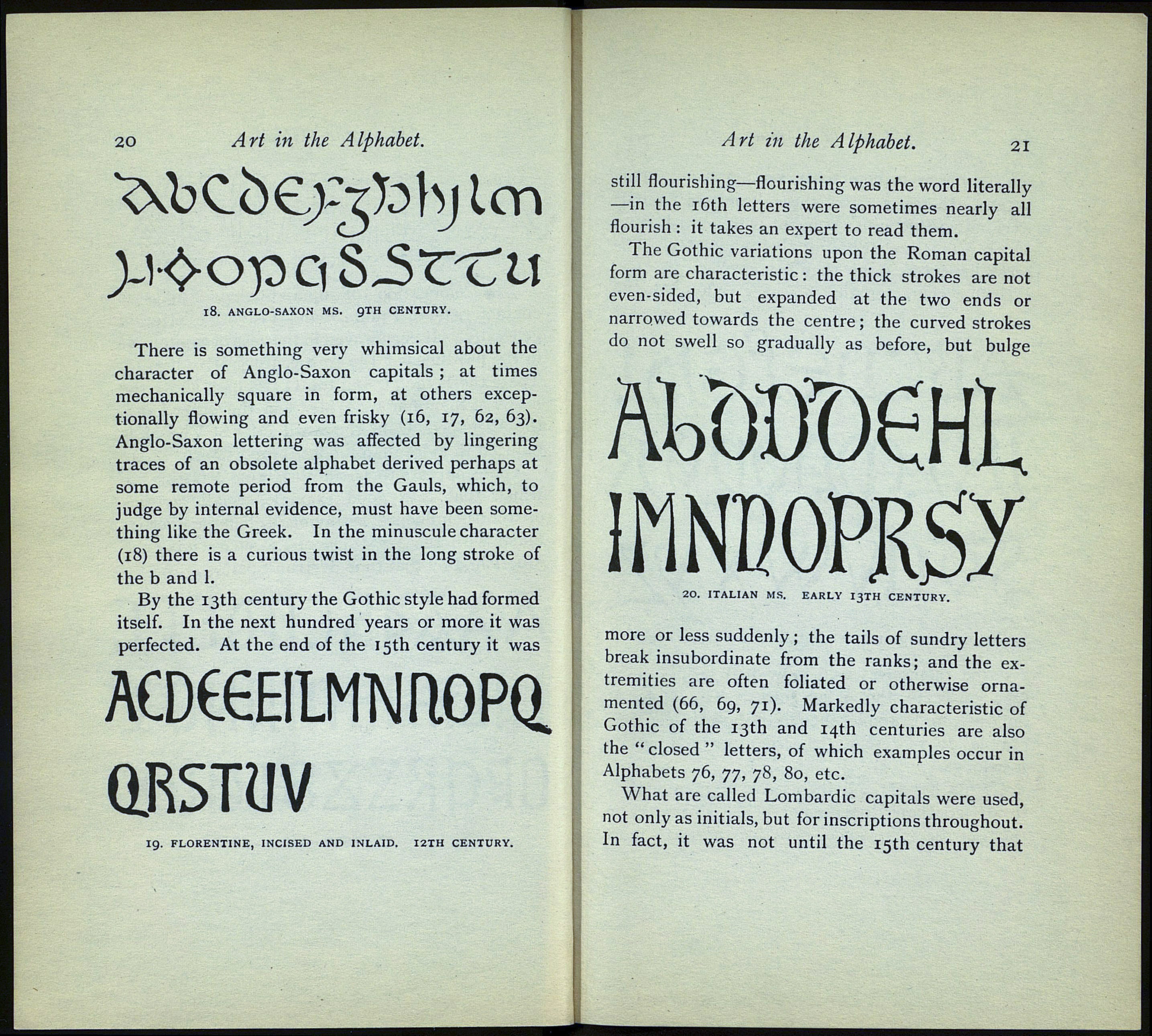

There is something very whimsical about the

character of Anglo-Saxon capitals ; at times

mechanically square in form, at others excep¬

tionally flowing and even frisky (16, 17, 62, 63).

Anglo-Saxon lettering was affected by lingering

traces of an obsolete alphabet derived perhaps at

some remote period from the Gauls, which, to

judge by internal evidence, must have been some¬

thing like the Greek. In the minuscule character

(18) there is a curious twist in the long stroke of

the b and 1.

By the 13th century the Gothic style had formed

itself. In the next hundred years or more it was

perfected. At the end of the 15th century it was

ACDÉŒILMNriOPQ.

QKSTUV

19. FLORENTINE, INCISED AND INLAID. I2TH CENTURY.

Art in the Alphabet. 21

still flourishing—flourishing was the word literally

—in the 16th letters were sometimes nearly all

flourish : it takes an expert to read them.

The Gothic variations upon the Roman capital

form are characteristic : the thick strokes are not

even-sided, but expanded at the two ends or

narrowed towards the centre ; the curved strokes

do not swell so gradually as before, but bulge

АШЮѲІ

ІГШОРКЗУ

20. ITALIAN MS. EARLY I3TH CENTURY.

more or less suddenly ; the tails of sundry letters

break insubordinate from the ranks; and the ex¬

tremities are often foliated or otherwise orna¬

mented (66, 69, 71). Markedly characteristic of

Gothic of the 13th and 14th centuries are also

the " closed " letters, of which examples occur in

Alphabets 76, 77, 78, 80, etc.

What are called Lombardie capitals were used,

not only as initials, but for inscriptions throughout.

In fact, it was not until the 15th century that

18. ANGLO-SAXON MS. 9TH CENTURY.