The Lowercase Letters

Elegant tools for communication that were

wrought to command respect and atten¬

tion for millenia, the capital letters

designed by the ancient Romans were—

and still are—perfect for inscribing on

monuments. However, for the commercial

documents, literature, correspondence,

and even the grocery lists and graffiti that

were as much a part of ancient Roman life

as they are of life today, these letterforms

were less than ideal. Think about it: How

would you like to write your next memo or

grocery list in slowly constructed capital

letters? (Neither did the Romans.) Form,

as always, follows function, and in due

course the capital letters began to change

to better serve these other, less monumen¬

tal, purposes.

Easier

Writing Styles

While monumental inscriptions were cre¬

ated by stonecutters, graphic communica¬

tion was produced by scribes. These were

specialists hired to record all kinds of

information on papyrus or other transient

writing surfaces, and their writing tools

gave them more freedom and flexibility

than the stonecutters had with their carv¬

ing implements. It is uncertain whether the

scribes adapted the inscriptional capitals to

meet their needs or developed their own

writing styles first, but over a period of

time three different forms of handwriting,

or hands, emerged that replaced the formal

capitals in everyday graphic communica¬

tion. These three styles came to be known

as the square capitals, the rustic or simple

capitals, and roman cursive.

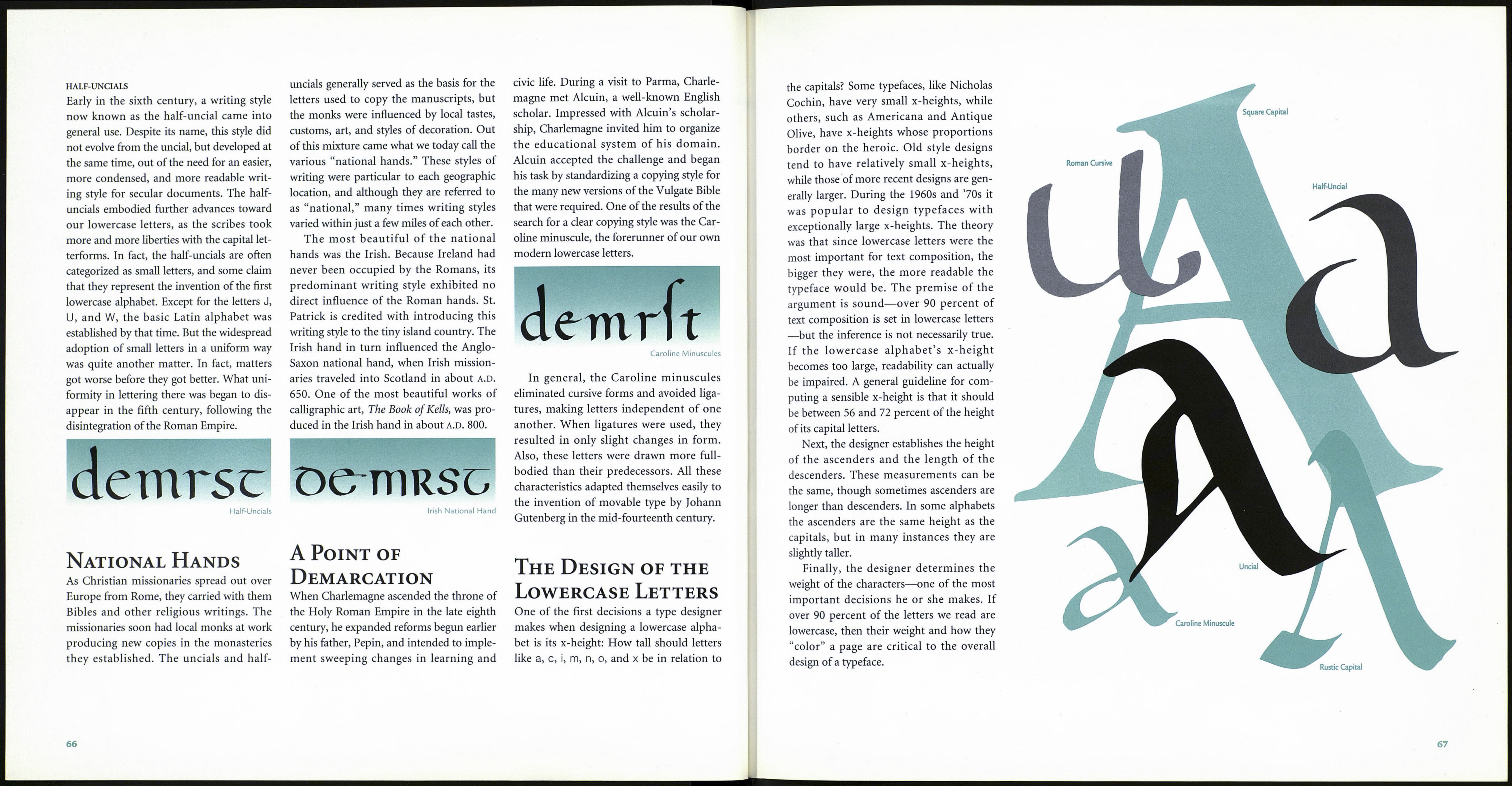

SQUARE CAPITALS

The square capitals are generally consid¬

ered an attempt to copy inscriptional let¬

ters. This writing style was reserved almost

exclusively for the production of the most

formal books and documents. The preci¬

sion and regularity of their forms shows

that these letters were drawn slowly and

carefully. Still, they were written more

quickly and with a more flowing hand than

was possible, or practical, in stone. As a

result, even though the square capitals

were rendered to resemble the capital let¬

terforms, they differed significantly from

the inscriptional forms.

DEMRST

Square Capitals

RUSTIC CAPITALS

The square capitals were proportionally

wide, and the material on which they were

printed, vellum, which was painstakingly

prepared from calfskin, was expensive.

Those who oversaw the production of

books and documents realized that the

costs for inscribing less important infor¬

mation could be reduced significantly if

the writing were done in letterforms that

were narrower and easier to draw, conse¬

quently saving both materials and time.

What have come to be known as the rustic

or simple capitals (rustica in Latin) were

the eventual solution.

0ШШ

Rustic Capitals

ROMAN CURSIVE

Not all writing had to be fancy. Most of it,

in fact, was used to record transactions,

keep accounts, draft correspondence, and

document other day-to-day business. The

writing style used for these relatively mun¬

dane applications differed from both the

square capitals and the rustic capitals.

Roman cursive was the ordinary business

and correspondence hand of the Romans

until approximately a.d. 500. It was used

for legal documents, notices posted on

walls announcing public games, signs

advertising houses to let, and other com¬

64

monplace interchanges. Since these kinds

of writing were not usually intended to be

permanent, they were often scratched in

wax tablets, in clay, or on masonry, or

written on papyrus. Sometimes they were

so carelessly written that the result was an

illegible scrawl. In spite of this, the very

speed and carelessness with which these

letters were written led to the present

forms of many of our small letters. The

roman cursive form was characterized by

the tendency of the writer to keep the pen

on the papyrus as much as possible while

writing; hence the term “cursive,” which

literally means “running.” That is, cursive

writing reflected the feeling of a hand

moving across the page as it created the

letterforms. An important innovation of

the roman cursive hand was the tendency

toward creating ascending and descending

parts on some of the letters. This probably

came about because it was easier to make

longer stems when writing quickly, as

opposed to the precise, short lengths used

in more formal and more slowly written

documents. Although the scribes were not

aware of it at the time, the ascenders and

descenders they incorporated into this

casual writing style helped establish an

important departure in design from the

capital letterforms.

While the three original Roman hands

were used for almost 500 years, two events

shortly following their development led to

some additional, and quite different, styles

of calligraphic writing.

Roman Cursive Letters for Books In addition to being a military and political UNCIALS Uncial letters grew out of an effort to documents. Applying the lessons they had Uncials were used for fine calligraphy Many scholars, referring to St. Jerome’s 0€ Uncials 65

juggernaut, ancient Rome was also a major

literary force. The Romans became the first

major producers of written documents.

Plays and poems were written, philosophi¬

cal treatises were published, and, once

Christianity became Rome’s state religion,

Bibles and religious commentaries were

needed for scholars and missionaries. All

this created great volumes of work for the

scribes, which in turn spawned two new

styles of writing: uncials and half-uncials.

develop a beautiful formal writing style for

Bibles and other important books. The

dilemma facing the scribes was that the

square capitals used for the most formal

books were costly to produce, and that the

rustica were not elegant enough for formal

learned from the cursive hand to the

square capitals, the scribes eventually

achieved the rounded forms of the uncials.

from the fourth to the ninth centuries a.d.

Usually a square-nibbed quill or reed pen

was used to create them. Uncials are espe¬

cially important because they are the first

obvious step toward the creation of our

current lowercase alphabet. Rounder

shapes for the A, D, E, H, and M evolved.

Try writing a capital A quickly in one

motion, or an H or an M, and you’ll begin

to see how our lowercase forms became

the “little brothers” of the roman capitals.

first use of the word, explain the term

“uncial” as indicating letters one inch in

height. Uncia, which means “one-twelfth”

in Latin, was a unit of measure used by the

Romans that is roughly equal to an inch.

The problem with this generally accepted

interpretation is that there were no uncials

of that size in the manuscripts of the peri¬

od. Hindsight suggests that St. Jerome

probably meant merely “large letters”

when he coined the term.