The Letters

The story of the U is also the

story of our V, W, and Y. In

fact, the story of our U begins

further back, with the story of

the sixth letter of our alphabet.

A creature called Cerastes,

sort of a giant snake or dragon,

was depicted as an Egyptian

hieroglyph, which represented

a consonant sound roughly

equivalent to that of our f This

character was the forerunner of

the Phoenician waw, the most

prolific of all their letters. The

waw gave birth to our F, U, V,

W, and Y. It looked like our

present-day Y and represented

the semiconsonant sound of w,

as in “know” or “wing.”

At some point between 900

and 800 B.C., the Greeks adopt¬

ed the Phoenician waw, using it

as the basis for not one but two

letters in their alphabet: the

upsilon, for the и sound, and

the digamma, for a sound that

was roughly equivalent to our f.

The upsilon character was

adopted first by the Etruscans,

then by the Romans. They both

used it to represent the semi¬

consonant w and the и sounds,

but the form looked, again,

more like a Y than either a U or

a V. In ancient Rome the

sounds of U, V, and W as we

currently know them were not

systematically distinguished;

context usually determined the

correct pronunciation. As a

tf VYv

result, the Romans’ sharp¬

angled monumental capital V

was used to express the w

sound in words like VENI (pro¬

nounced WAY-nee) and as the

vowel и in words like IVLIVS

(pronounced YEW-lee-us).

What happened to the Y?

After the Romans conquered

Greece in the first century B.C.,

they added the Greek Y to their

alphabet for use in the Greek

words they had acquired. The

sound value attributed to it by

the Greeks was unknown in the

Latin language, and when the

Romans used it in the adopted

Greek words it took on the

same sound as the letter I. The

early English scribes frequently

used Y in place of I, particularly

when the minuscule i, which at

that time did not carry a dot,

appeared in close proximity to

the minuscules m, n, or u.

These characters were some¬

times quickly written as a series

of unconnected strokes, mak¬

ing it difficult for the reader to

distinguish them.

In the medieval period, two

forms of the U, one with a

rounded bottom and one that

looked like our V, were used to

represent the v sound. It wasn’t

until relatively recently that the

angular V was retained to rep¬

resent our v sound, and the

version with the rounded bot¬

tom was officially relegated to

the single job function of rep¬

resenting the vowel u.

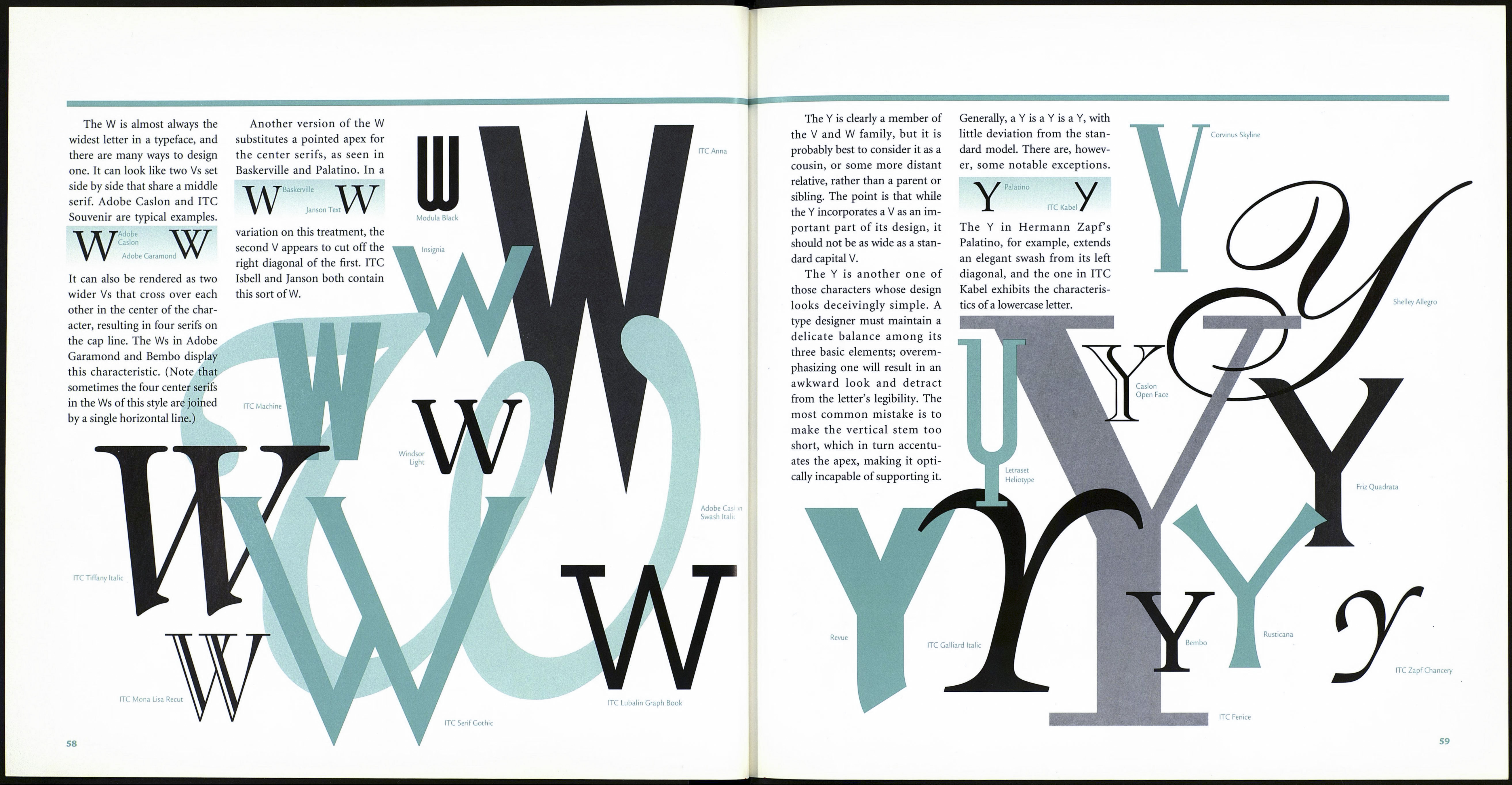

The graphic form of the W

was created by the Anglo-Sax¬

ons around the thirteenth cen¬

tury. They called their new let¬

ter wen. This innovation arose

from their attempts to distin¬

guish the various sounds that

were represented by the U. They

used a V for both the и and v

sounds, but wrote the V twice

for the w sound. Eventually the

two Vs were joined to form a

single character. This early liga¬

ture endured to become part of

the common alphabet. Rather

than use what they considered

to be an alien letter, the French

preferred to double one of their

own. They chose the U and

called the letter double V, which

the English called a “double U.”

The double V form is retained

in typographic letterforms, but

because of the need for speed in

writing, the handwritten letter

looks more like a double U.

Senator Demi

The U is classified as a

medium-width letter, but

because it does not appear on

the Trajan inscriptions it has

no monumental model.

The U can be rendered in

three different ways. The first is

u u u

Albertus Trajan Caslon 540

an enlarged version of the low¬

ercase u, where the left stroke

curves to meet a vertical right

stroke. This design can be

found in such typefaces as

Albertus and Corvinus. In this

configuration the right stroke

also has a baseline serif that

extends to the right. The second

version of the U is symmetrical,

and can be seen in faces like

Trajan and ITC Novarese.

Here two equal-weight vertical

strokes are joined by a baseline

curve. Finally, there is the

thick-and-thin version, in

which the left stroke is heavy

and the right stroke is a hair¬

line. For examples of this treat¬

ment, look at faces like ITC

Benguiat and Caslon 540. The

thick-and-thin version, which

has no bottom serif, is the most

popular design.

Bodoni

Poster

The V is a medium-width

character, about two-thirds as

wide as it is high. In serif type¬

faces its vertex is almost always

pointed, in which case the point

must fall below the baseline at

least as far as the rounded

characters, ensuring a correct

optical height and maintaining

a strong baseline in text copy.

ITC Fenice

V

ITC Clearface

V

In ITC Tiffany and ITC Clear¬

face, for example, the first

stroke of the V drops below the

baseline, and the second stroke

joins it slightly above.

Ariadne

ITC Beesknei

Shelley Volante

Omnia

AG Book

Rounded

Monotype

Onyx

In some typefaces the parts

of the serifs that extend into

the counter are longer than

those that face outward. This is

VX T

ITC Legacy Serif \r

usually the designer’s attempt

to overcome some of the V’s

inherent spacing problems. For

examples of this approach,

look at Letraset’s Caxton and

ITC Century.

Latin Extra

Condensed

ITC Korinna