Adventure and Art

47. Gower.John (1325P-1408).

De Confessione amantis.

London:Thomas Berthelet, 13 March 1554. F".

This, the third edition of Gower's Confessio amantis,

was printed in London by Thomas Berthelet in 1554;

originally published by William Caxton in 1483.

Berthelet, who reprinted Caxton's Confessio Amantis,

began publishing in about 1525, eventually replacing

Worde's frequent collaborator, Richard Pynson, as the

King's printer.

The Rutgers copy bound in panel-stamped calf with

gilt on board edges; it was acquired for the Libraries

through a library gift fund established by Charles H.

Brewer, '25, and Mrs. Brewer; 733181.

Reference: STC 12144

S cnolar- Printers

Aldo Manuzio—better known by the Latinized form

of his name, Aldus Manutius (1449 or 1450-1515)—

was the first great scholar-printer, whose engagement with

classical learning, close contact with learned communities,

and forceful business practices enabled him to bring into

print the unpublished cornerstone texts of Greek and

Roman literature—particularly Greek philosophy. Aldus

published the editio princeps of Hesiod (1495), Aristotle

(1495-1498), Aristophanes (1498), Sophocles (1502), Plato

(1513), and more than twenty other seminal authors of

antiquity. As Barbara A. Shailor has noted in this catalog,

if Aldus had not secured these texts in print, their survival

beyond the manuscript era would have been uncertain, and

Western literature would have lost some of its earliest

guiding lights.

Aldus figures prominently in the history of type design

as well. In collaboration with the ingenious goldsmith

and punch-cutter, Francesco Griffo of Bologna, he created

typefaces that largely determined the appearance of

72

The First One Hundred Years of Printing

sixteenth-century scholarly publication. His Roman,

designed in 1495, modernized Jensons prototypical

Roman (see #16). By reducing the size of Jensons epi-

graphic capitals, he brought them into greater harmony

with the minuscules. (Bembo, the typeface of this catalog,

is an early twentieth-century imitation of Aldus's Roman,

and named after Cardinal Pietro Bembo (1470-1547), the

author of the original fifteenth-century text in which it

appeared). Aldus's four Greek fonts, produced between

1495 and 1502, modeled upon the contemporary free-

flowing handwriting of Immanuel Rhusotas rather than

the ancient more formal hand beloved by early humanists,

are both praised as technologically innovative (Barker, 11),

and criticized for "want of legibility" (Davis, 14), for their

excessive use of ligatures. Finally the type designed by

Griffo upon the 'cancelleresca corsiva' of the Papal

Chancery (probably the hand of Bartolomeo Sanvito),

first printed as the face of a complete text in the Aldine

Vergil of (April) 1501, marks the entrance into the world

of what we know familiarly as italic. Highly regarded in

appearance—Erasmus esteemed italic to be "the neatest

types in the world," and economical—its slanting lines

allowed more letters to appear per page, and therefore

required less paper, italic became almost as popular as

Roman during the sixteenth century. As exhibited here

(see items #32, 49, 50, 51), the texts of small, scholarly

publications of the sixteenth century—or, rather, classical

texts for the nonscholarly ideal reader, who had the

education and leisure to read classical literature, but whose

reading matter was not wholly dictated by his profession—

appeared completely in italic, a practice that may seem

strange to those of us who are accustomed to seeing italic

used for emphasis or to set off words in a foreign language.

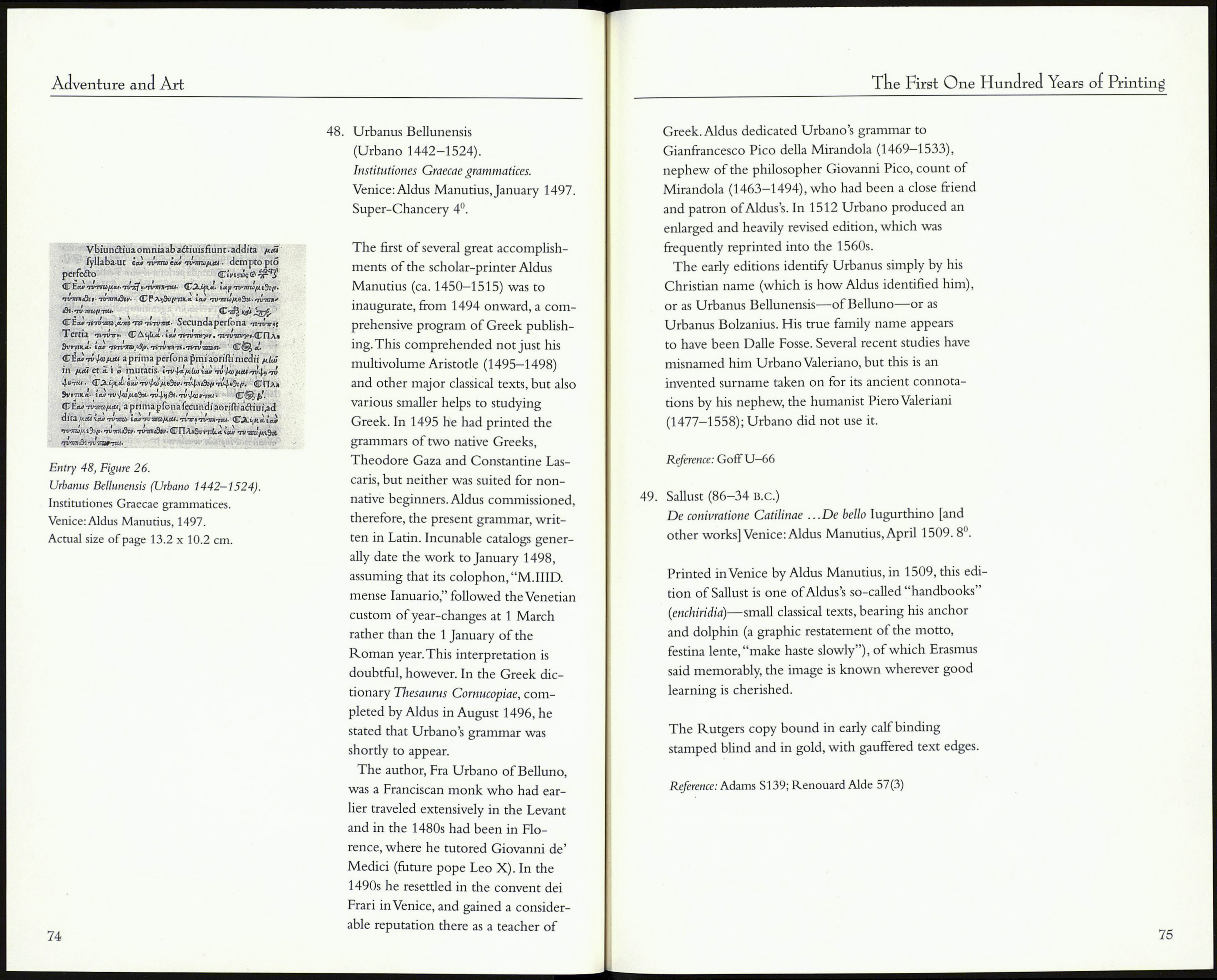

73