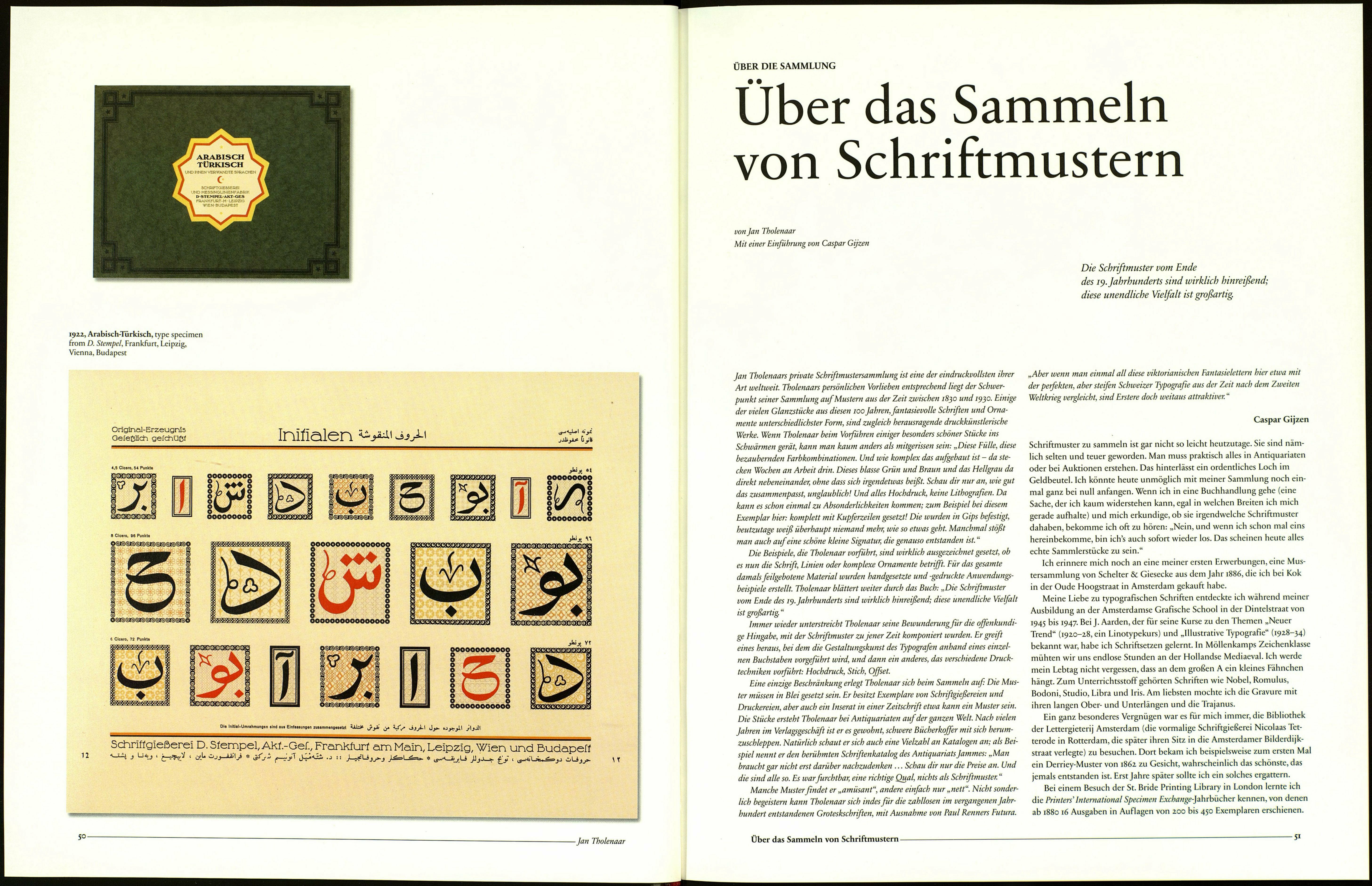

fìo.-2eichen.

Nr. 1 pr. 100 St. M. 1.70 = fi. 1.— ¡i. W.

je jya ж jw л* ж л*, л? jw jw JW jw m ж ж

Nr. 2 pr. 80 St. M. 1.70 = fl. 1___ii. ЛѴ.

M JW Jtä Jtä JW M M M M M M M M M

Nr. 3 pr. 00 St. M. 1.70 = fl. 1___o. W.

M M M .M M M' M M M M M

Nr. 4 pr. 40 St. M. 1.70 = H. 1___ö. W.

M M M M M M M № JVs M

Nr. 5 pr. 20 St. M. 1.70 = fl. 1___о. W.

№ M M M M Xs № M

Nr. в pr. St. 10 Pf. = 06 kr. о. ЛѴ.

Nr. 7 pr. St. 15 Pf. = 08 kr. ii. ЛѴ.

м мм JM M JM

Nr. 10 pr. St. 10 Pf. = 06 kr. S. ЛѴ.

Nr. 11 pr. St. 15 Pf. = 08 kr. B. W.

№ M : : № Ж № №

Nr. 8 pr. St.

Nr. 9 pr. St. Nr. 12 pr. St.

Nr. 13 pr. St.

№ JW N° №

18 Pf. = 10 kr. ii. W. 20 Pf. = 12 kr. ö. W. 18 Pf. = 10 kr. «. W. 20 Pf. = 12 kr. ö. W

Nr. 14 pr. 60 St. M. 1.70 = fl. 1.— ö. W.

16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16

Nr. 15 pr. 40 St. M. 1.70 = fl. 1.— ». W.

Ф av n m го n m n m

Nr. 16 pr. 30 St. M. 1.70 = fl. 1.— Ö. W. Nr. 17 pr. 16 St. M. 1.70 = fl. 1.= о. ЛѴ.

№ № № № Jtë % № Ш

.1. t!. llllHt & Oo. in Wien.

48-

-Jan Tholenaar

1887, Schriftproben, Schriftgiesserei

und mechanische Werkstätte J. H. Rust (

Co., Vienna

(Dasei, ¡neu

Amerikanische

Tiegeldruck-Schnellpreeee.

Papicr-StereotypiiiApparat.

Inni-re 1І.Ьоіпі|СГІІыв íd'/.Xl Cm.

Pr.1« util reieMMt rutilait. В. iV.L— »t.rr..lr pie,- rtleho гЯХЯ С«-

. "br« . . .BIO— I'reUfl. І!й,-

Papii!fSi:linriilt!iiiiischine. Wiener Pttrforir-Maechini.

«rlmiUlr...;. :.l Cm. B. П

bid and was able to acquire it. The day after I received the specimen by

post, I was at the antique fair in Haarlem. And what did 1 find there?

Two bound specimens by Hoffmeister, an earlier one (the first, only

containing vignettes) and a later one.

A couple of years ago, I lent some material to the Gutenberg Museum

in Mainz for an exhibition of type specimens. On that occasion, I was

allowed to browse through the library, and, to my amazement, I found a

number of unusual, old, and in some cases rare specimens that the muse¬

um staff themselves had hardly been aware of. They also had some unusual

things from Dutch foundries from the 19th Century, including specimens

from Hendrik Bruyn & Сотр., Broese & Сотр., Elix & Co., and J. de

Groot (1781). Of these I unfortunately have only the de Groot. For the

record, all other items mentioned in this book are in my own library.

I'd like to mention one last specimen: that by the typefounder Louis

Vernange in Lyon, from 1770, which comprises 64 pages. The three other

known copies are all slightly smaller. The bookseller I bought it from told

me he had never come across one before in the 35 years of his career.

Well, those are some examples from my own collection. I keep my

bound copies in bookshelves, arranged by height, because of the space

they take up. The slim specimens are stored in archive boxes, classified

by foundry and date. Although everything is recorded in the computer,

I sometimes forget and buy one I already have.

The value of type specimens is largely determined by their physical con¬

dition. The 1768 Enschedé specimen could fetch tens of thousands of euros;

the 1628 Vatican specimen even more. For a good bound specimen over

100 years old, you have to pay hundreds of euros; slim specimens cost around

20 euros, and a nice Rudolf Koch specimen will set you back more than

100 euros. Prices for rare or special things—unusual items such as an 80-page

Peter Behrens stitched specimen from 1902 or the 1928 Curwen Press speci¬

men—are slightly higher than average. Also unusual in relation to their

peers are the three rare 1833 Andreaische broadsheets I once purchased from

Jammes and the double 1926 Ashendene Press sheet I mentioned earlier.

Is there anything else I want? Well, there's quite a list, at the top of

which used to be the three Bodoni specimens, Fregi e majuscole (1771), Serie

di majuscole (1788), and Manuale tipografico (1818). I now have the last one,

and it is the pride of my collection.

Quite a lot has been written about specimens and foundries. The stan¬

dard works include Chronik der Schriftgiebereien by Friedrich Bauer (1928,

first impression 1914), Les livrets typographiques des fonderies françaises créées

avant 1800 by Marius Audin (1964, first impression 1933), British Type Speci¬

mens before i8}i by James Mosley (1984), Schweizer Stempelschneider und

Schrifigiesser by Albert Bruckner (1943), Type Foundries of America and Their

Catalogs by Maurice Annenberg (1994, first impression 1975), and, last but

not least, Type Foundries in the Netherlands by Charles Enschedé, translated

and adapted by Harry Carter (1978, first impression 1908).

If you think that lead type is never cut or cast these days, you are mistak¬

en. Not so long ago, the American poet Dan Carr felt he should design his

own typeface for his poems and cut the dies himself. An appendix to the

aforementioned Matrix featured Regulus, which turned out to be a really

nice typeface. I immediately wrote to Carr's Golgonooza Letter Foundry &

Press to order the bibliophile collection of the first application, asking for a

real type specimen.

In the past, setting up a well-stocked hand-setting shop meant a consid¬

erable investment. These days, anyone who produces printed matter on the

computer can choose from an infinite range of typefaces on the Internet

that cost only a couple of euros each. If you buy 10 at the same time, you

get a free mountain bike.

The same printing methods were used for 500 years—and, suddenly, it

was over, thanks to Mr. Senefelder. Type foundries that made only lead type

have disappeared. Some changed with the times and built photosetting

machines—sometimes successfully, like Berthold (they had been engraving

the matrices for the German Linotype system since 1900), and sometimes

with less success, like Deberny & Peignot, who went bankrupt with their Lumi-

type system. Others already had a sideline; Enschedé, for example, had a print

shop, and Lettergieterij Amsterdam dealt in printing machines. The commer¬

cial type foundries disappeared, but fortunately there is a foundation in the

Netherlands by the name of Stichting Lettergieten that presents the former

art of typography. Anyone who loves the old business should support them!

Once, when I was visiting the Amsterdam University library, a librarian

casually remarked, "We've got 70 meters of type specimens here." I must

have blushed. At home, I took out a tape measure and established that I

measured up to perhaps half of that. A lesson in humility.

Collecting Type Specimens

49