■•¿tuoi» ppiW« l-Wu. iMiJ -Ъ- •¡Bili*. ■

U іям pop*. шЛЛ («fr*«» taw» снми

A ■ С l) E F G Hl J К LM SO ГЦ.» ST U

Гпіиа. И»«.

ABCDEFGH] jKLUNOrQRSTU

Кл i*:. N» ■-

JMCDÍ¿FCHI7ILLMSorzilSVUr*'

ІииГКіІИГ, Гіі« Ret«. N.I î¥c D ÉfgÎÏ ïi 'Л»Ліо7ц»?г' Гк.Ім... Nal. И^ІсЬ^гпшараЛттЛ^тІ -tata, н «- AlCDirOHI JKLMNOfqiiTUVwi ¿ІЬОТгеіІТуЛмыІГ/іКгТѴГІГ Ы*Ъ*ъKtufMImo« И»ь [•еаігТяімьмкогцдіі bvwí îSroK Sjki-ыko ?^Г* T О * W X и. «^. -ы °—w^-. ■*'."T*-t" ïïcКияTt^uÑoTaíríuv»! rei itt¡íijtLiá»er*.*4VririftM ??*^_^!?H?7îî—S! .ggSj-ig ■.■ffitMBWT.TTSft« üb f.tirera «пит?}« «Ssasëçias ЁШіДііРІІ ЩрЩ ¡¡P§Bjg 1785, Specimen of Printing Types, William Caslon, London At the age of 13, William Caslon (1692- extremely old specimen, after hemming and hawing for more than a year, One special example in my collection is a Bodoni Greek specimen, I find the 19th-century book letters rather dull; this is primarily the letter, on the other hand___I already sang the praises of those thousands of Victorian typefaces and their infinite variety above: classic, decadent, Around 1820, heavy competition arrived in the form of lithography. So where did I find all those extraordinary type specimens? Well, I was 38 Jan Tholenaar popular style now known as Caslon Old William Caslon (1692-1766) trat im Alter sam, womit die Geschichte einer der net. Am neuen Standort des Unterneh¬ À 13 ans, William Caslon (1692-1766) la promotion du savoir chrétien) pour Through Knuf's bookshop, I acquired specimens from the G. W. Ovink Naturally, with the advent of the Internet, I've also started looking for In the early 1980s, the famous Parisian antiquarian bookseller Jammes Incidentally, the Jammes catalog reminds me of one kind of type In his bibliography Die deutsche Schriftgießerei (1923), Oscar Jolies men¬ Two-Line Great Primer. Quoufque tandem Two-Line Engliíh. Quoufque tandem abu¬ Two-Line Pica. Quoufque tandem abutere, Double Pica Roman. Double Pica Roman, a. Double Pica Italic. Paragon Roman. Quoufque tandem abutere, Catilina, Paragon Italic. £>uoufqae tandem abutere^ Catilina^ patientia noflra t quamdiu nos etiam 4BCDEFGHIJKLMN Great Frimer Roman. Great Primer Italic. Great Primes Bodv, English Roman, Quouique tandem abutere, Catilina,- patien¬ Laroe-bodied Екпы5н Roman, English Roman, No i. Quoufque tandem abutere, Catilina, patien¬ Pica Bodv, English Roman, No 2. English Roman, No 2. Eng/iß Italic. Collecting Type Specimens - -39

■I j« fcfc Дяд-Ц )j

r— ivH-i r>ñ. ~Ы arta .«£*, »Ы

lUi p4«t.jJM .atnAii— """ft ~"

AlClltFCillIJICLMNOPUHSTUV

вЙЙММЙЕ

1766) was apprenticed to a London

engraver and in 1718 established his own

engraving business. After beginning a

type foundry two years later, the book¬

binder John Watts engaged him to design

and cast typefaces for his bindings.

William Bowyer, an eminent London

printer, noticed one of these books, and

this was the beginning of the most suc¬

cessful English type foundries at that

time. Initially, Watts, Bowyer, and his son-

in-law James Bettenham, also a printer,

backed Caslon financially. In 1720, his

first year as a type founder, Caslon pro¬

duced a new typeface for the Society for

the Propagation of Christian Knowledge

to be used for a Bible in Arabic. He print¬

ed a sample page to market the Arabic

type and on the flyer printed his name in

a typeface design that would become the

in the hope that no other interested party would appear who was prepared

to buy it without negotiating the price. 1 went to fetch the specimen

myself, in this case from London. You don't entrust something like that to

the post. It was the 1628 Brogiotti, the Stampa Vaticana. The significance of

this old specimen is demonstrated by the fact that a facsimile edition was

produced. I can summarize a few of the specimens in my possession of

which facsimiles exist: the 1742 Claude Lamesle, the 1773 Du Sieur Dela-

cologne, and the Enschedé specimens from 1768 and 1773. Further 18th-

century specimens in my collection include the 1748 Enschedé, the 1764

Fournier, the 1740 Louis Luce, the 1778 Gillé, the specimen by J. de Groot of

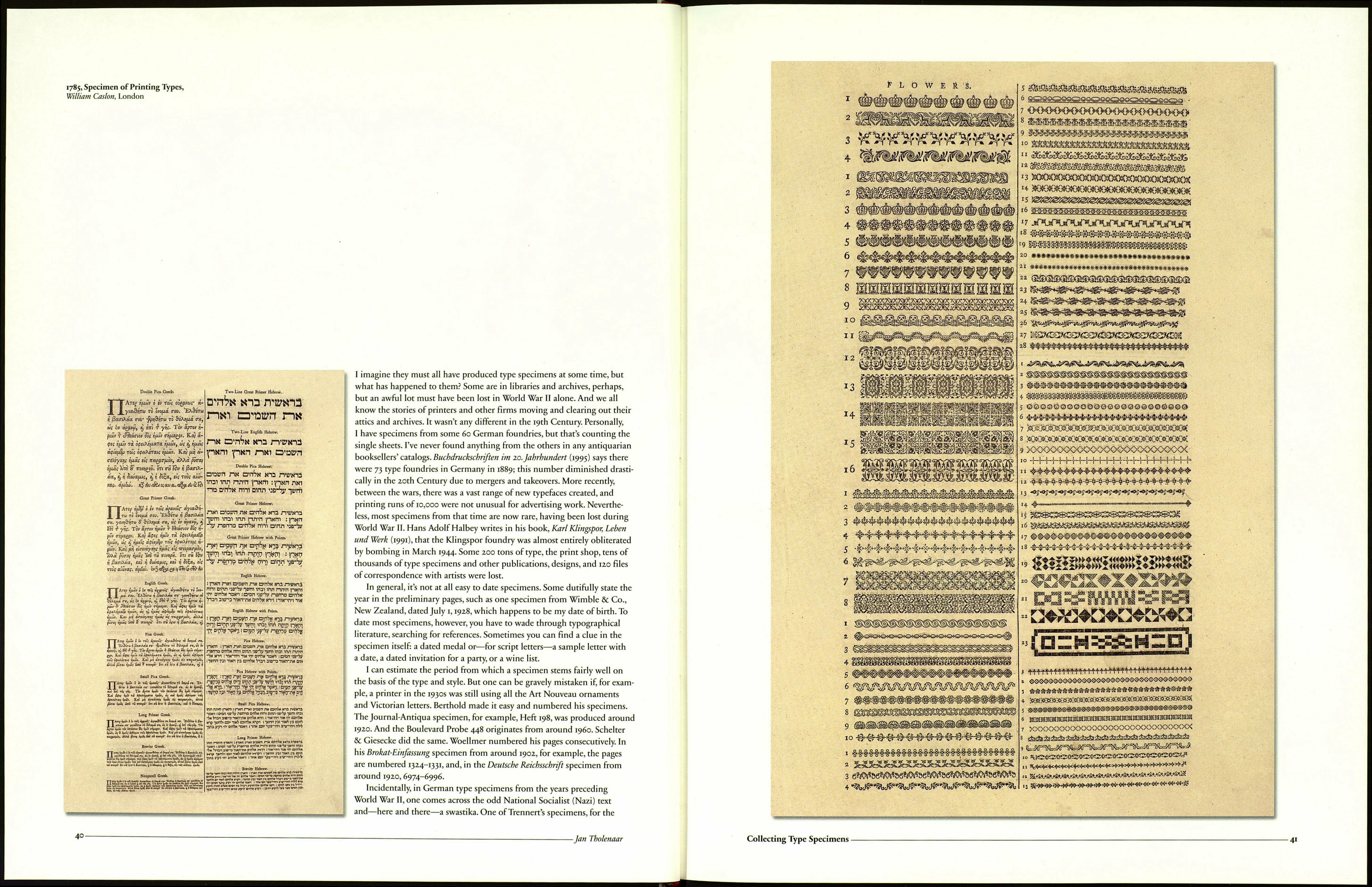

The Hague from 1781, the 1783 and 1789 Wilsons, the 1785 Caslon—with 21

pages of wonderful, ingenious applications of flowers—the 1787 Fry, and

the 1799 specimen from Imprenta Real in Madrid. I also have a number of

lovely 19th-century specimens by, for example, Bodoni (1818), Didot (1819),

and Fry (1824). It is a fair number for a private individual, but only a frac¬

tion of what they have in public collections. There are major collections of

this sort in, for example, the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris, Amsterdam's

university library (including the Tetterode collection and the Royal Society

of the Dutch Book Trade library), the St. Bride Printing Library, and the

Newberry Library in Chicago. I, myself, have quite a few old Caslon and

Figgins specimens, but if I consult the St. Bride Foundation catalog from

1919 (then already almost 1,000 pages), I count 70 Caslon specimens, prima¬

rily from the 19th Century, and 31 Figgins specimens.

which is unusual in that the first name, Giambatista, is spelled with two

t's rather than three (the typical spelling is Giambattista). Each of the 28

pages, the letters ascending in size, has its own unique typeface. The speci¬

men was published in 1788, the year in which his most important speci¬

men, Serie di majuscole, from which Greek is derived, appeared. In Birrell &

Gamett's exemplary sales catalog of famous typefounders' specimens (1928),

the slim volume is referred to as "extremely rare," with a price of 15 guineas

(the aforementioned Vaticana, Lamesle, and Enschedé are offered for sale at

15 to 18 guineas). I bought Bodoni's specimen at a Beijers auction for con¬

siderably more. The Parisian publisher and bibliophile Renouard once said

of Bodoni, "In the evenings, conversing with his friends and in distin¬

guished company, during meals, he was always busy with his typefaces,

justifying a matrix, filing a die, designing a capital."

realm of Didot and Bodoni. A Turlot specimen from around 1885, pub¬

lished in Paris, for example, has 27 pages of 8-point typefaces and they all

look practically the same, each just a tiny bit smaller or larger or fractional¬

ly different in thickness from the next. I can't see the point. But the display

chic, touching, hideous, course or refined, straight or italic, égyptiennes,

américaines, italiennes, syriennes, elzéviriennes, babyloniennes, pompéiennes,

japonaises, milanaises, orientales, latines, letters in two colors, innumerable

fantaisies, Zierschriften, Grotesken und Antiguas, Fraktur-Schriften, Rustic (tree-

branch letters) ... the list is endless. And then there are the filets, vignettes,

lettrines, coins, ornements, Zierleisten, Polytypen, Untergrunde, Einfassungen,

and books full of Messinglinien.

While the book printers, with their rigid, rectangular blocks of lead, were

limited in their possibilities, lithographic draftsmen could put any design

onto a plate, as they did for stocks and bonds, calligraphic visiting and

business cards, calendars, and other commercial printing work. I have a

number of examples of these in my collection. In their fight to compete

with lithographers, typefounders devised ways of setting lead lines diago¬

nally or in a circle and engraved more and prettier ornaments. I already

mentioned the 1862 Charles Derriey, which measures more than 40 x 30

centimeters. The first part, "Spécimen," shows the vignettes. These are

wonderful designs, sometimes for two- or three-color printing. Then come

the "Caractères ornés," the "Trais de plumes," the sophisticated "Coins com¬

poses, filets, passe-partouts," and so forth. The second part,"Album," demon¬

strates applications. This is so magnificent, so stylish, and in such delicate

colors that I can only describe it in superlatives. And to think that it was all

printed on a hand press: a tremendous feat, considering the wide spectrum

of colors. I have one other comparable specimen: The one from the

Imprimerie Royale from 1845 also contains such an album. If you have ever

used a setting stick, you will realize how terribly complicated it must have

been to produce those pieces of printing. The competition with lithogra¬

phy also led to ridiculous abnormalities and unnatural typography.

always a good customer of the antiquarian bookseller Frits Knuf (Vendôme,

France), one of the few specializing in bibliography in the broadest sense.

Style. Caslon then cast a number of non-

roman and exotic styles, including Cop¬

tic, Armenian, Etruscan, Hebrew, and

Caslon Gothic, the latter being his ver¬

sion of Old English or black letters. In

1734, Caslon published the first catalog

for his type foundry, presenting a total

of 38 typefaces. He then moved to the

Chriswell Street Foundry, where his son

and generations after him would contin¬

ue the business for over 120 years.

von 13 Jahren bei einem Londoner Gra¬

veur in die Lehre, 1718 machte er sich

mit einem eigenen Graveurbetrieb selbst¬

ständig. Nach der Eröffnung einer Schrift¬

gießerei zwei Jahre darauf erhielt er von

dem Buchbinder John Watts den Auftrag,

Schriften für dessen Bucheinbände zu

entwerfen und zu gießen. Auf eines die¬

ser Bücher wurde der bedeutende Lon¬

doner Drucker William Bowyer aufmerk¬

erfolgreichsten englischen Schriftgieße¬

reien der damaligen Zeit begann. Bowyer

und Watts sowie Bowyers ebenfalls im

Druckgewerbe tätiger Schwiegersohn,

James Bettenham, boten Caslon in der

Frühphase seines Gewerbes finanzielle

Unterstützung. Im Jahr 1720, seinem

ersten Geschäftsjahr als Schriftgießer,

fertigte Caslon für die Society for the Pro¬

pagation of Christian Knowledge eine neue

Schrift für eine arabische Ausgabe der

Bibel an. Zur Vermarktung dieser arabi¬

schen Schrift stellte er ein Musterblatt

her, auf dem sich sein eigener Name in

einem Stil abgedruckt findet, der heute

als Caslon Old Style geläufig ist. In der

Folgezeit goss Caslon eine Reihe exoti¬

scher, nichtlateinischer Entwürfe, darun¬

ter koptische, armenische, etruskische

und hebräische Schriften, sowie die Cas¬

lon Gothic, Letztere eine Variante jener

Schriftarten,die man als Old English oder

„black letters" (Frakturschrift) bezeich¬

mens in der Chiswell Street führten nach

Casions Tod sein Sohn und dessen Nach¬

folgegenerationen das Geschäft noch

mehr als 120 Jahre lang fort.

devient apprenti chez un graveur de

Londres. Il s'installe comme graveur

indépendant en 1718, et, deux ans plus

tard, ouvre sa propre fonderie de carac¬

tères. C'est le relieur John Watts qui lui

demande de dessiner et de fondre des

caractères pour ses couvertures de livres.

William Bowyer, célèbre imprimeur lon¬

donien, remarque un de ses livres et c'est

le démarrage de l'une des plus floris¬

santes fonderies de caractères d'Angle¬

terre. A ses débuts, Caslon reçoit le sou¬

tien financier de Watts, Bowyer, et de

son gendre James Bettenham, également

imprimeur. En 1720, la première année

de la fonderie, il crée une nouvelle police

de caractères pour la SPCK (Société pour

l'impression d'une Bible en arabe. Pour

pouvoir vendre cette police arabe à

d'autres imprimeurs, il imprime une

page d'échantillon sur laquelle son nom

s'étale en caractères qui sont à l'origine

de la célèbre police connue aujourd'hui

sous le nom de Caslon Old Style. Caslon

grave ensuite un certain nombre de carac¬

tères non romains et exotiques comme

les Coptic, Armenian, Etruscan, Hebrew

et Caslon Gothic, ce dernier étant sa

version de Old English. En 1734, Caslon

publie le premier catalogue de la fonde¬

rie qui présente un total de 38 caractères.

Il déménage ensuite sa fonderie sur Chis¬

well Street, d'où son fils et plusieurs géné¬

rations après lui dirigèrent l'affaire fami¬

liale pendant plus de 120 ans.

library, for example. In England, I bought the Lamesle from Tony Appleton.

Other suppliers were Keith Hogg, Questor Rare Books, S. P. Tuohy, Barry

McKay, and the London antiquarian booksellers Marlborough, Maggs, and

Quaritch. There are a couple of booksellers in Germany who sometimes

have a reasonable Buchwesen range. In America, I have a good relationship

with Bob Fleck of Oak Knoll, and the Delacologne specimen came from

Kraus in New York. With a lot of rummaging and a bit of luck, I sometimes

find something at an antiquarian book fair, a book market, or a collectors'

fair. And then there are the Dutch auctions, such as Bubb Kuyper's. Some¬

times I buy a whole stack for a single book I'm missing. Once or twice

on a viewing day, I've left a note in such a pile, after which the buyer has

contacted me and I've been able to purchase the desired item.

type specimens online. I've bought them from booksellers in places from

Switzerland to Sweden, via their online catalogs.

published a typography catalog. This included the library of the ancient,

bankrupt type foundry Deberny & Peignot, with more than 400 chiefly

unusual and rare specimens. The prices were high and, at that moment,

there was no way I could even think of buying anything. With a lump in

my throat, I laid the catalog aside. It was not until several years later that

I was able to purchase a few specimens from this wonderful Jammes cata¬

log. It was of some consolation to me that, before the catalog was released,

various pieces had already been offered to the Bibliothèque nationale, the

St. Bride Printing Library (which had to draw on special funds from the

British Library), and the Newberry Library. The Taylor Institution in Oxford

had also bought a number of important items. It was rather a disappoint¬

ment for me, but a large proportion of the type specimens described had

already found a good home even before the catalog came out.

specimen that doesn't interest me: the smoke impression. If a letter

engraver wanted to make an impression of a die, he did it not with ink,

but with soot from a smoking candle, which gives an especially sharp

impression.

tions specimens from some 120 19th-century type foundries. There were

far more, though, such as small in-house foundries affiliated with a printer.

abutere, Catilina,

Quoufque tandem a-

butere, Catilina^pa-

tere, Catilina, patientia

Quoufque tandem abutere',

Catilina, patientia noflra?

Catilina, patientia noftra ?

Quoufque tandem abutere', Ca¬

tilina, patientia nqflral quam-

Quoufque tandem abutere Ca¬

tilina, patientia noftra? quam-

diu nos etiam furor ifte tuus e-

ludet ? quem ad finem fefè ef-

Quoufque tandem abutere, Ca¬

tilina, patientia noftra ? quam-

diu nos etiam furor ifte tuus e-

ludet? quem ad finem (eft effre-

Щири/que tandem abutere, Catili¬

na, patientia noflra ? quamdiu

nos etiam furor ifle tuus eludei?

patientia noftra? quamdiu поз etiam

furor ifte tuus eludet ? quern ad fi¬

nem iefe effrenata jaftabit audacia ?

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO

Quoufque tandem abutere, Catilinat

patientia noftra ? quamdiu поз etiam

furor ifte tuus eludet ? quern ad finem

fefe effrenata jacìabit audacia ? nihilne

te noâumum prxfidium palatii, nihil

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOP

Quoufque tandem abutere', Catilina, pa¬

tientia noflraf quamdiu nos etiam furor

ifle tuus eludei? quem ad finem fefe ef¬

frenata jaSlabit audacia? nibilne te noc-

ABCDEFGH1JKLMNQP

N01.

tia noftra? quamdiu nos etiam furor ifte tu¬

us eludet г quemad finem fefè effrenatajae-

tabit audacia? nihilne tc nocturnum prxfi¬

dium palatii, nihil urbis vigilia;, nihil timor

populi, nihil confenfus honorum omnium,

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQJlST

Quouique tandem abutere, Catilina, patien¬

tia noftra? quamdiu поз etiam furor ifte tu¬

us eludet? quern ad finem fefe effrenata jac-

tabit audacia F nihilne te nocrurnum pnefi-

dium palatii, nihil urbis vigilia;, nihil timor

populi, nihil confenfus bonorum omnium,

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOP QJl ST,

tia noftra? quamdiu nos etiam furor ifte tu¬

us eludet? quem ad finem fefe effrenata jac-

tabit audacia? nihilne te nocbirnum prxfi¬

dium palatii, nihil urbis vigilia:, nihil timor

populi, nihil confenfus bonorum omnium,

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQJlST

Quoufque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia

noftra? quamdiu nos etiam furor ifte tuus elu¬

dei? quem ad finem fefe efirenata jaebbit au¬

dacia? nihilne te nocturnum pnefidium palatii,

nihil urbis vigilia:, nihil timor populi, nihil

confenfus bonorum omnium, nihil hie mum-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOP QJt ST

Quoufque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia

noftra? quamdiu nos etiam furor ifte tuus elu¬

dei? quem ad finem fefe effrenata jacìabit au¬

dacia? nihilne te nocturnum prxfidium palatii,

nihil urbis vigilia:, nihil timor populi, nihil

confenfus bonorum omnium, nihil hie muni

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQ.RST

Quoufque tandem abutere, Catiline, patientia nof¬

tra ? quamam not etiam fitrtr ifit turn rlutici ?

quem ad finem fefe efrenata jaSlabit audaciaì ni¬

bilne te noOvrnum prtrfidium palatii, nihil uriti

ABCDEFGHlJKLMNOPSiRS